Legitimate Defense

Russia reopens the Kharkov front to stretch Kiev's defensive reserves and to fragment Kiev's ruling class cohesion in the wake of Zelensky's legitimacy crisis.

President Zelensky’s mandate expires on the 21st of May. Swirling in the center of a larger geopolitical maelstrom, in Ukraine democratic legitimacy is but a flimsy shield. It failed to protect Viktor Yanukovych from the Western-backed street mobs in 2014. The Ukrainian Constitution’s ambiguity on leadership during periods of martial law will lead in the coming months to increased strife and fragmentation within Ukraine’s ruling class. The soon-to-be unelected Zelensky is still solidly backed by the Western democracies and by those in Ukraine still pushing a total victory policy in the war against Russia.

In a display of Western solidarity with the Ukrainian strongman, US Secretary of State Tony Blinken issued a diktat seemingly declaring Zelensky as Ukraine’s president for life:

Last year, Zelensky said that he could hold elections if the US and other Western countries paid for them and if Ukrainian legislators agreed to amend the constitution. He later ruled out the idea and there’s been no pressure from Ukraine’s Western backers to hold a vote despite the claims that the proxy war is a fight for democracy.

In a speech at the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute, Blinken said the US and Europe had been helping Ukraine build “democratic pillars,” including “free and fair elections,” but said a vote can only happen when the “conditions” are right.

“That’s why we’re working with the government and civil society groups to shore up Ukraine’s election infrastructure. That way, as soon as Ukrainians agree that conditions allow, all Ukrainians – all Ukrainians, including those displaced by Russia’s aggression – can exercise their right to vote. People in Ukraine and around the world can have confidence that the voting process is free, fair, secure,” Blinken said.

Gen. Valery Zaluzhny, Ukraine’s former commander-in-chief who was recently appointed ambassador to the UK, has long been rumored to be a potential presidential candidate in a future election, although he hasn’t announced his intention to run.

Earlier this year, a poll in Ukraine found Zelensky would lose to Zaluzhny in a presidential election. The poll found that 41% favored Zaluzhny in a first-round election, while only 23.7% would vote for Zelensky.

Blinken’s ambiguous use of the term “all Ukrainians” could mean that elections are only possible when Ukraine recaptures all lost territory and returns to its 1991 borders. In other words, elections are on hold until Ukraine launches a massive offensive to not only recapture Donetsk, Lugansk, Kherson, and Zaporozhy oblasts, which voted overwhelmingly to join Russia—but also Crimea—where a referendum to join Russia won with 97% of votes in 2014.

By acting as the Ukrainian Constitutional Court, Blinken is locking in a maximalist, total victory platform that everyday Ukrainians increasingly reject. The Ukrainian demographic machine’s failure to provide enough manpower, combined with the West’s anaemic arms industry’s inability to supply sufficient firepower, means that Ukraine will never re-establish its 1991 borders by military means. And so short of a fragmentation of the Ukrainian ruling class, Zelensky may indeed rule for the rest of his life.

In a move that will only deepen his crisis of legitimacy, Zelensky refused demands to send his case to Ukraine’s actual Constitutional Court.

Zelensky's interview responses ignited a fervent discussion in both the mainstream media and social networks. Numerous political analysts and commentators highlighted the discrepancy between martial law and Ukraine's constitution. The consensus reached was that the Constitutional Court should have been the venue for resolving this dispute.

Instead, on Feb. 25, Zelensky said that the opposition's demands for early presidential elections were part of planned ideological sabotage by the Kremlin. Zelensky labeled elections as a "poor idea," but went further: "I consider this a traitorous stance in Ukraine."

The allegation of treason carries significant weight in times of war. Nevertheless, this did not deter those advocating for a presidential election. Zelensky's political opponents increasingly asserted that his presidency should conclude on May 20, and have raised doubts about his continued legitimacy in office.

Minister of Justice Denys Maliuska tried to prevent the political boat from rocking. He said now is not a suitable moment to seek clarification from the Constitutional Court in an interview with BBC News Ukrainian on May 10.

"Such an appeal would imply legitimate questions and doubts, warranting resolution by the Constitutional Court," he said. "Given the country's communication and security challenges, openly questioning the president's authority would be a grave error."

Ukraine will use a mid-June “Peace Summit” in Lucerne, Switzerland to flaunt the West’s recognition of Zelensky’s legitimacy. Russia has not been invited, and many of Russia’s BRICS partners will refuse to attend. As time goes on, the rest of the world will increasingly refuse to recognize Zelensky.

One danger is that after Zelensky’s constitutional mandate expires, Russia will no longer respect her promise not to target the embattled President. This risk was heightened after the recent assassination attempt on Slovakian Prime Minister Robert Fico by a gunman with possible links to Ukrainian intelligence services.

Since such a move by Russia would appear gauche and heavy handed, instead of directly destroying Kiev’s leadership, on May 10th, Russia launched a modest offensive in Ukraine’s northern Kharkov region. Russian strategists know that stretching the current frontlines is the best catalyst towards Ukrainian disintegration—both militarily and politically.

The Ukrainian Telegram channel Rezident reports that due to the deteriorating military situation in Kharkov, Zelensky cancelled all foreign travel for the foreseeable future. Rezident is rumoured to have close ties to ex-army chief Valery Zaluznhy, which may explain why Rezident shares so much solid information on internal Ukrainian political strife.

Furthermore, the Washington Post reports the dictatorial ways of film producer and Zelensky’s top deputy Andriy Yermak are worrying the Western allies:

Now, however, the legitimacy of the president and his top adviser are about to face even bigger challenges as Zelensky’s five-year term officially expires on May 20. Ukraine’s constitution prohibits elections under martial law. But as Zelensky stays in office, he will be vulnerable to charges that he has used the war to erode democracy — seizing control over media, sidelining critics and rivals, and elevating Yermak, his unelected friend, above career civil servants and diplomats.

It seems natural that an actor like Zelensky playing the role of President would feel most comfortable with his producer pulling the levers of power backstage. Neither Zelensky nor Yermak came to their jobs with any military or government experience. Both do show a talent for staying on narrative and pleasing the international press. Yermak is cunning in his defense of Zelensky and was instrumental in firing Zaluznhy. The knives may soon be out for both men.

In the meantime, some Ukrainians are treating this small-scale invasion as a catastrophe, given the loss of over 100 square kilometres of land in the first few days of the offensive. But given the realities of any normal defense in depth concept, Ukraine so far seems to have acted efficiently in slowing the Russian advances in a zone less then 10 kilometres from the border.

While an offensive in the Kharkov region was widely expected, it is still not clear how serious this push is. Clever strategists are opportunistic—they take what the defense gives them. So far Russia seems to be only pushing a modest number of reserves into exploit this initial breach of Ukraine’s first defense line. Russia’s stated goal is to create a buffer zone along the border to stop Ukrainian shelling of Russian territory.

Russia’s immediate goal is certainly not the capture of Kharkov. With only a maximum force estimated at 50,000 troops, Russia will not attempt to capture a city of more than a million people. The goal is to stretch Ukraine’s defense and in particular to attrite Kiev’s mobile defense reserves.

A deeper, more insidious Russian goal is to drive a wedge of discord within Ukraine’s ruling class. In The Chechen Gambit: Will a Ukrainian Kadyrov Rise? I described the Ukrainian ruing class factional strife as globalists versus nationalists. The ethnically Jewish President and ethnically Russian commander-in-Chief may be grudgingly accepted by hardcore Ukrainian nationalists in the best of times while the sweet promise of victory waifs through the air. But as the doom of defeat engulfs the nation, these elite battalions of ultras will fall back among themselves—realizing the globalist ruling class gains every advantage by throwing them into the fire. There have already been several cases over the past few months of neo-Nazi formations, held in defensive reserve, refusing battle in situations they deem to be hopeless.

Defense-in-Depth

American military commentators, no matter how brilliant their kernels of wheat may be, often throw up too much home-team, geopolitical gaslighting, that must be waded through. One huge exception is Stephen Biddle, a professor at Columbia University and the author of many brilliant books on military theory. If the Ukrainian War has proven any military theorist to be prescient, it is Biddle and his masterpiece, Military Power: Explaining Victory and Defeat in Modern Battle. Biddle argues that there are two primary styles of defense in modern war. Strategists either employ a variation on a powerful single line of fortressed defense, or deploy a much more flexible and complicated defense-in-depth concept, which relies on several layers of protection against invasion. These two concepts are poles on a continuum and any individual situation may contain elements of both strategies.

Ukraine built several fortress zones during the eight years between the 2014 coup d'état and Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. Most of these Maginot Line-style static defense zones worked well and took years to fall to Russia. The bastion of Avdiivka is a powerful example. But as these strongholds tumble one-by-one along the front line, Ukraine must increasingly employ a more orthodox defense-in-depth system.

Since the attackers have the initiative, they decide where to mass troops to form the differential concentrations needed for attack. Without powerful fortifications, the defenders can never hope to forward deploy large enough forces along the front line to stop any such mass attacks. Plus it is dangerous to place so many troops so close to the point of impact. As Biddle explains:

Against modern firepower, simply digging in is insufficient—static defenses have been fatally vulnerable since at least 1917. Instead, the more fluid conduct of modern system defense demands much the same exposure-reduction tactics of cover, concealment, dispersion, suppression, combined arms, and independent small unit maneuver that modern system attackers require, albeit adapted to the particular problems of the defense.

Cover and concealment, for example, are essential to prevent attackers from concentrating their firepower on known defender locations. Geometrically arranged, quasi-permanent trench lines are easily surveyed from the air and permit attackers to build plans around known locations for at least the initial defenses they will encounter in the early stages. (p. 44)

There are three key elements to a defense-in-depth scheme: zones of depth, reserves and counterattack. Typically there are three zones of action, an initial front zone which in the case of Kharkov would follow the border with Russia. The purpose of this zone is to delay the initial onslaught down for a day or two to give the reserves enough time to move into place to absorb the shock in the battle zone. This zone is where the real fighting will take place. Since the soldiers in the front zone are low-skill and sacrificial, highly trained motivated mobile reserves have to be available on the operational level ready for speedy transfer to the penetrated zone. In Ukraine, these elite forces tend to be the ultra nationalist battalions. Their job is to stop the attack in its tracks and to then launch devastating counterattacks which seek to reclaim the land lost in the front zone. Again from Briddle:

Depth, reserves, and counterattack are very effective if done right, but doing them right is more difficult than implementing a static defense. Depth, for example, disperses troops; like dispersion on the attack, this complicates command and control, increases the burdens on junior leaders, and challenges morale among troops who may feel dangerously isolated. Morale can be especially hard to maintain in the forwardmost positions, which are both thinly garrisoned and too close to the enemy to be reinforced before a major attack would overrun them. Soldiers often know this yet must stay and fight at least long enough to break the attack’s momentum. This requires either conscious self-sacrifice or the ability to conduct a fighting withdrawal under pressure. Withdrawal under fire is among the most technically demanding maneuvers in modern land warfare; conscious self-sacrifice in defense of an untenable position requires a very high order of discipline and motivation. (p. 48)

The defender’s rear zone is the prize the attacking forces are targeting. If Russian forces can break through Ukraine’s roving defensive reserves, then the path is open to wreak havoc, force chaotic withdrawals, hit critical lines of communication, destroy weapons stockpiles, and turn parallel to the front line and attack defending troops from their rear. So far Russia has relied on air power to attack Ukraine’s rear zones.

In Kharkov, despite Western funding earmarked for fortification construction, the front zone was not very well protected. To be fair, building defensive structures is difficult during active hostilities as Russian drone and artillery can disrupt any such construction efforts.

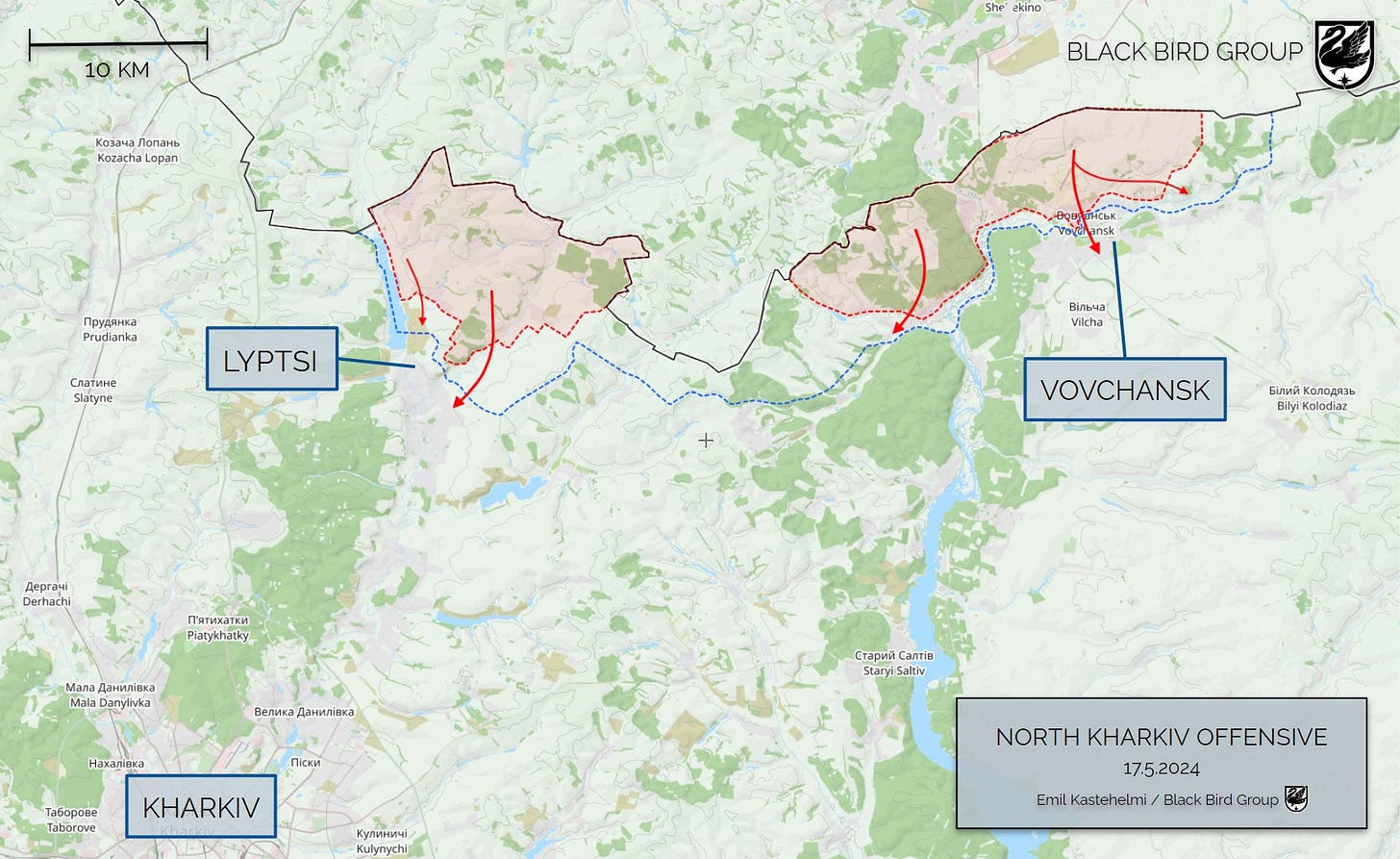

Nevertheless, in Kharkov the Russian advances were eventually met by Ukrainian mobile reserves. Currently the invasion is bogging down in the towns of Lyptsi and Vovchansk, both important logistics hubs for the Ukrainian army in the region. In the coming weeks Russia will capture these towns and advance further towards Kharkov, but the city itself should not be in any danger given the current size of Russia’s invasion force.

Had Ukraine done a better job reinforcing this region they would have needed to scramble fewer elite troops. With Russia’s much improved drone, aerial and satellite surveillance, as Ukraine’s manpower and weaponry break cover to move into new areas, Russia has a greater chance of spotting and destroying such assets en route. It is difficult to understand the level of Ukrainian losses but on Telegram there are constant videos of Ukrainian artillery and armoured vehicle losses. No doubt Russia is also suffering losses, but at what rate? The difference between the two militaries is that Russia’s industrial might can replace losses while Ukraine is stuck begging the West for a few table scraps.

In response to the Russian incursion into Kharkov, Ukrainian officials are blaming the United States for not allowing them to directly attack Russian territory with American arms. But both Lyptsi and Vovchansk were locations used by the Ukrainians to shell civilian areas of the Russian city of Belgorod. This new Ukrainian narrative hides the fact that Ukraine has wasted so many Czech-supplied RM-70 Vampire shells slaughtering civilians in Belgorod over the past few months. Perhaps Ukraine should have saved some of that artillery to target gatherings of Russian troops along the border?

Ukraine is naturally using the Russian incursion to demand more weapons from Western donors. Zelensky goes so far as to imply that Kharkov itself will fall if the West doesn’t supply two more Patriot air defense systems.

“The situation is very serious,” Zelenskyy said. “We cannot afford to lose Kharkiv.”

As he stood near the injured soldiers, he was very clear that the delay in U.S. aid has had a direct impact on the war, and the situation along the northeastern border. Hundreds had lost their lives or been wounded in the last few days, he said. Many were soldiers from this region, so it was important for him to be there, supporting them, he said.

Is it America’s fault, we asked him, what’s happening now in Kharkiv?

“It’s the world’s fault,” he replied. “They gave the opportunity for Putin to occupy. But now the world can help."

<…>

“All we need are two Patriot systems,” he said. “Russia will not be able to occupy Kharkiv if we have those.”

In contrast, NATO’s high command has a more realistic view of the situation in Kharkov:

Russia’s ongoing offensive in Ukraine doesn’t have the legs for a breakthrough, NATO’s supreme allied commander for Europe said Thursday.

“I know the Russians don't have the numbers necessary to do a strategic breakthrough,” Christopher Cavoli told reporters after a meeting of the alliance’s defense chiefs at NATO headquarters in Brussels.

“They don't have the skill and the capability to do it, to operate at the scale necessary to exploit any breakthrough to strategic advantage," said the U.S. general, but added: "They do have the ability to make local advances and they have done some of that.”

This is so far a fair assessment for the Kharkov incursion. As of this writing Russia has captured 16 towns and 170 square kilometres of territory in the Kharkov region but the invasion force may have reached its culmination point. Nevertheless, as Cavoli hints, with such a modest invasion force, it is doubtful that the Russians intended a strategic breakthrough into Ukraine’s rear areas. A more likely intent was to simply attrite Ukraine’s mobile reserves, observe Ukrainian movements, and to further strain Ukrainian ruling class cohesion through the loss of territory. It remains to be seen whether Russia indeed has the capability to act at scale and achieve a strategic breakthrough on the operational level. Their Soviet grandfathers certainly could.

The map below shows in dark green the areas Russia held in the Kharkov region in 2022. The pink zones in the north represent the extent of the current invasion. Given that this map is several days old the pink zones of Russian control have doubled in the north.

Russia will very likely follow this Kharkov incursion with similar limited invasions in the Sumy and Chernihiv regions. These upcoming attacks from the north will eventually threaten Ukraine’s capital Kiev. It’s doubtful Russia would ever attempt to capture such a large city—Russia’s strategic intent is to pull Ukraine’s military center of gravity northward. This opens the way to Russia launching a major attack towards Kherson and this war’s ultimate prize: Odessa.

Danube: Why the BRICS need Odessa

Ukraine is slowly approaching the threshold of collapse. But since Russia has not yet soundly defeated Ukraine on the battlefield, there is no peace deal available which will come close to satisfying Russian demands. Russia’s priority is first and foremost a neutral Ukraine firmly embedded into the “Russian World” which forecloses any NATO or EU membership. That is the basis of any peace discussions. As argued in Civilizational Clashes, it is possible that Russia would cede Western Ukraine to the Western powers. The most important issue now is Odessa.

In Black Sea Matters, I argued the war in Ukraine is ultimately about control over the Black Sea. And as Chinese President’s Xi Jinping’s recent visits to Serbia and Hungary hint, there are huge geopolitical stakes in controlling the Odessa region and the outlet of the Danube River to the Black Sea.

Hungary, Serbia, Austria, Czech Republic and Slovakia are all landlocked and any potential trade with the BRICS could be blocked if the EU controlled Odessa. These former Hapsburg Empire subjects tend to be much more culturally conservative than Western Europe. They joined the European Union for economic enrichment, but are realizing that “cultural enrichment” is the price of entry to the Western club. If Russia controls the Odessa region, this would give these nations access to trade with Russia and China and open the possibility to them joining the BRICS trade organization.

The Russians would prefer to control Odessa through negotiating a future puppet regime in Kiev. Increasingly Western leaders are somewhat naively calling for Ukraine to start negotiations. They think they can “freeze” the conflict at the drop of a hat. Once the West realizes the extent of Russian demands, they will be forced to continue expending resources for the foreseeable future to maintain control over Odessa and the Danube River outlets. Only a clear Russian victory on the battlefield will bring Odessa under her sway.

Given Zelensky is now free of any democratic mandate, he would have the political wiggle room to negotiate some sort of peace. But Russia will not want to negotiate with a President of questionable legitimacy. What if Zelensky were to sign a peace deal than a few months later Ukraine’s Constitutional Court declares his post-May 20 reign illegitimate? Russia knows the West is nowhere near ready to concede to her demands and will profit from Zelensky’s legitimacy crisis by refusing any peace talks, if they were ever to be proposed in the first place.

The Three Acts of World War 1

Years of trench warfare and static lines in the Donbass brings to mind the quagmire of the Western Front of World War 1. These long, bloody and dull second acts obscure the brief period of fast-moving manoeuvre warfare which occurred in the first months of each conflict. In WW1, the Germans swept through Belgium and into France in an audacious sweep seeking to attack the rear of France’s main forces along the border of the Alsace-Lorraine region. This troubled region served a similar role as the Donbass does in today’s conflict.

The meat grinder battles in Passchendaele, Ypres, Verdun and the Somme are etched in history as peak examples of human depravity. The place names Bakhmut, Robotyne, Maryinka and Bilohorivka do not have the same ring to them but are similar examples of bloody stalemates—albeit on a much smaller scale—occurring during the middle section of the war in Ukraine.

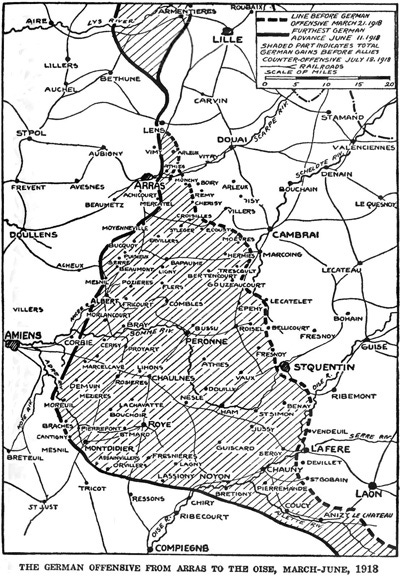

First the Germans in a minor fashion and then the Allies in a major way eventually broke the stalemate and brought World War 1 to an end. This third act was not as exciting as the first—the movements were more modest. Nonetheless, in Operation Michael, the Germans managed to capture more than 3000 square kilometres and pushed the British back to the River Somme.

If the opening act of WW1 highlighted the infantry, the second act was dominated by artillery. In a sort of Hegelian sublation, the German innovation was to combine the two, enabling the possibility of surprise. From Briddle:

In the new approach, surprise was restored by restricting the preparatory artillery program to a brief but intense “hurricane barrage” designed not to destroy but merely to suppress the defenses. This temporary suppressive effect was exploited by independently maneuvering infantry teams armed with hand grenades and portable light machine guns; these were trained to exploit covering terrain to find their own way through hostile defenses via the path of least resistance. These independently maneuvering assault teams were much better able to sustain their advance through the depths of a hostile defense; as the brief barrage denied the defender advance warning of the time or place of attack, defenders found it much harder to amass sufficient reserves in time to repel the attack before it broke through. (p. 33)

As Basil Liddell Hart explains in his History of the First World War, the French choice of defensive doctrine helped increase the German advances:

[General Duchene] indeed, bears a still heavier responsibility, for he insisted on the adoption of the long-exploded and wasteful system of massing the infantry of the defence in the forward positions. Besides giving the enemy guns a crowded and helpless target, this method ensured that once the German guns had made a bloated meal of this luckless cannon-fodder, the German infantry would find practically no local reserves to oppose their progress through the rear zones. In similar manner all the headquarters, communication centres, ammunition depots, and railheads were pushed close up, ready to be dislocated promptly by the enemy bombardment.

Petain’s instructions for a deep and elastic system of defence had evidently made no impression on General Duchene <…> (p. 489)

Germany’s rush to the Somme failed to achieve any strategic goals and only resulted in exhausting manpower and morale. From this point on Germany lost all offensive potential. The Allies turned the minor German ebb tide into their own massive flow by applying the new German offensive tactics. Reinforced by two million fresh and eager Doughboys from America, in early August, 1918 the Allies launched their Hundred Days Offensive. After pushing the Germans back for 25,000 square kilometres, Germany finally threw in the towel and sued for an armistice.

Ukraine is fervently hoping NATO will come to their rescue in the same way the Americans saved the Allies in WW1. Despite grandstanding by effete European leaders, it’s unlikely enough NATO troops will ever save Ukraine. The more salient similarity to the Great War is that Ukraine has lost any and all offensive potential for the foreseeable future.

If the Ukrainian War will also fall into the three pattern, the key variable will be the evolution of Ukrainian defensive schemes. In the first act, the Russians were easily able to grab territory, with a modest amount of troops—but only in areas where Ukraine lacked powerful fortifications. The second act was a double movement, as Ukraine learned to execute a defense-in-depth, they were able to push undermanned Russia forces out of some areas lacking fortifications, such as Kherson and Kharkov. At the same time, Russia was developing the weapons and skills needed to destroy the Donbass fortifications. The third and final act will be the waning of Ukraine’s ability and resources to execute defense-in-depth for the remainder of the war.

As the depletion of Ukraine’s defensive reserves intensify, Ukrainian ruling class solidarity will crumble. Secretary Blinken’s strategy to defend Zelensky’s legitimacy is to build a rhetorical fortress backed by the democratic legitimacy of the Collective West. At the same time, Zelensky’s power broker Andriy Yermak is conducting a defense-in-depth by manipulating the levers of Ukrainian political life.

Russia will work to crush both defensive schemes of Zelensky’s legitimacy in the informational and political realm with the same ardour her military is showing in depleting Ukraine’s defensive battalions.

Great article! “The Russians would prefer to control Odessa through negotiating a future puppet regime in Kiev.” Do you think Russia will trust a future puppet regime with this resource hanging over Russia’s head? Or will Russia have to formally annex in order to always have leverage over a puppet regime? I’ve said elsewhere that I don’t believe that Russia wants to (or can, frankly speaking) control much of Ukraine and is content with the 4 new oblasts, Crimea and Nikolaev and Odessa in the future. I really don’t think they want to do more than that due to the huge financial resources involved. Curious to hear your thoughts!