Civilizational Clashes

How Samuel Huntington's concepts of torn and cleft countries, articulated in "The Clash of Civilizations," can help in understanding events in Russia, Ukraine and the United States.

Russian President Vladimir Putin was re-elected on March 17th, winning an eye-opening 87% of the vote. Haters howled despite this number closely matching Putin’s approval ratings, as recently measured by pro-Western organizations. It certainly didn’t hurt Putin’s victory margin that the Communists—the main opposition party—didn’t bother campaigning against the sitting President. Suffice to say that Russian and Western elections are two very different species.

Putin’s win comes as multiple indicators show Russia is heading towards a decisive victory over the West in Ukraine. Russia’s economy is not only surviving Western sanctions; it is indeed flourishing. Diplomatic triumphs among the Global Majority are translating into an increased military presence in Africa. Jumping from success to success, is Putin’s election victory the crowning climax of his long career?

While Putin is surely happy with Russia’s current position, nevertheless this St. Petersburg native had two career goals when he came to power, and to date he has only accomplished one. Today we see these two goals as contradictory but in the year 2000, when Putin was first elected President, this was not universally the case. Putin wanted to resist the US unipolar global hegemony and at the same time pull Russia closer to the West. Putin’s domestic mission was to once and for all mend Russia’s historic tear between forces pulling it in two directions. Elites had long tried to push Russia towards the liberal West while the majority preferred the statist Eurasia model. Young Putin was among those who sought to integrate Russia into the prosperity of Western institutions.

Refusing to budge on its unilateral “rules-based” global order, the West instead embarked on a full-court geopolitical press on a weakened Russia’s crumbling sphere of influence. One obvious target was Ukraine, a flailing state straddling the fault line between the West and Orthodox East. Fuelled by Western intelligence services, an ideological Chernobyl of Ukrainian nationalism spewed out of the region of Galicia in Western Ukraine. This only exasperated tensions with Eastern Ukraine, known as Malorossiya (Lesser Russia) whose civilizational roots were firmly anchored in the Russian World.

As it turned out, Putin refused Western vassalhood, and it fell upon him to abandon his dreams of joining the liberal West and to instead build Russia’s current Eurasian-style state capitalist economic machine. Putin won his recent election as a Eurasian statist—the ideological opposite of what the young, dashing Putin dreamed of becoming.

Perhaps Putin playing this reverse role is for the best. 19th century German statesman Otto von Bismarck asserted the seemingly paradoxical idea that political parties should take the helm to carry out policies which they previously opposed.

If reactionary measures are to be carried, the Liberal party takes the rudder, from the correct assumption that it will not overstep the necessary limits; if liberal measures are to be carried, the Conservative party takes office in its turn from the same consideration.

Putin’s idea of Russia forming an alliance with the West seems bizarre today. But in the years following the Cold War, it was not at all a radical idea. A Western-Russia partnership was one of the key policy recommendations that flowed from Samuel Huntington’s “The Clash of Civilizations.”

Torn and Cleft: Huntington’s Civilizational Lines of Fracture

Huntington’s study of eight major world-civilizations, was a reality-based counterattack on Francis Fukuyama’s post-Cold War triumphalist The End of History and the Last Man.

Published in 1992, Fukuyama heralded an American unipolar hegemony as the final stage of mankind’s development:

What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western Liberal democracy as the final form of human government.

Western democracy was fetishized so convincingly by Fukuyama that his messianic narcissism was internalized by many in the US ruling class. In Fukuyama’s idealist construct, the world was reduced to a battle between good and evil. Western democracy was tasked with the burden of taming uncivilized nations, many of which needed a helping hand—or an outright invasion—to one day rise to the moral heights of the West.

For Fukuyama’s position to be correct, each and every of the seven non-Western civilizations that Huntington describes would need to jettison their own historical, cultural and deep civilizational roots to become so many hybrid versions of America.

Fukuyama is a conservative cosmopolitan who sees a dominant US as the globe’s moral compass and the international system’s only hope for future order and peace. George W. Bush’s regime ran on these principles.

A slight variant is liberal interventionism, where the US remains the world’s beacon in the night, but human rights along with gay and gender theory get promoted over questions of traditional moral authority. Much of the US foreign policy establishment falls into one or the other of what is for all intents and purposes a single camp.

While Fukuyama's vision is hegemonic and expansionist; Huntington's is defensive and isolationist. Huntington (and John Mearsheimer) are realists who see geopolitics as scenes of anarchy. Military strength, cycles of history and balances of power are more relevant than messianic idealism. A realist knows that the lessons from the long war between Athens and Sparta recounted in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War are just as relevant today as they were 2500 years ago.

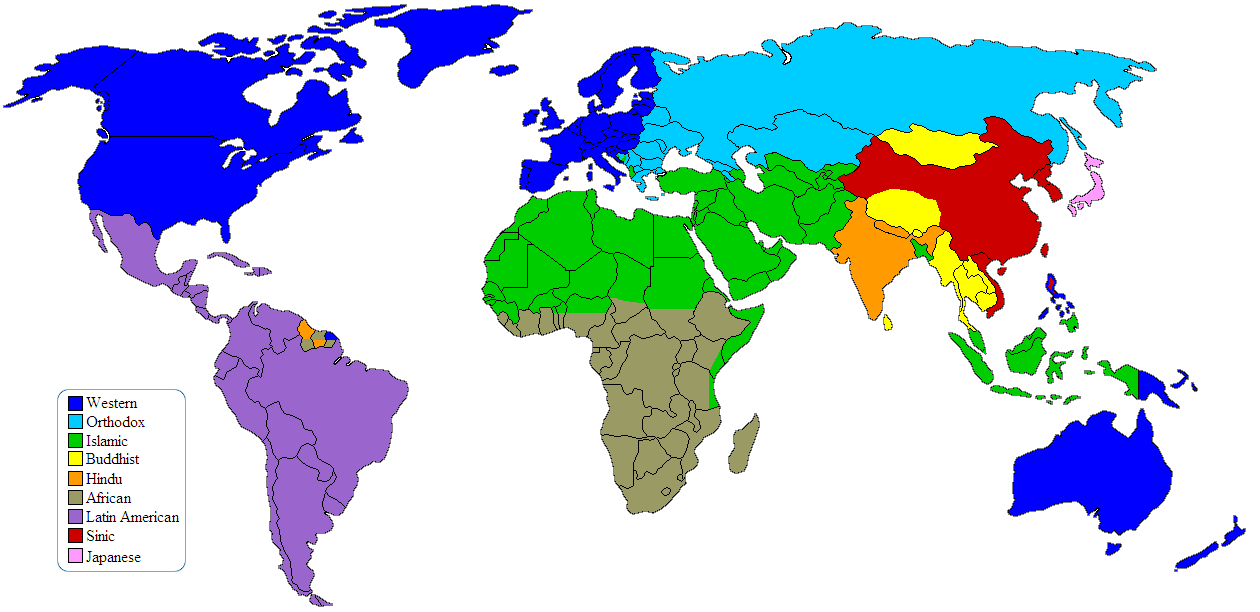

Being much more grounded in reality than Fukuyama, Huntington implicitly declared the future to be multipolar by depicting a churning and seething struggle among eight major world civilizations: Western, Confucian, Japanese, Islamic, Hindu, Slavic‐Orthodox, Latin American, and African. Huntington was deeply concerned about a Confucian-Islamic partnership and pushed the West to develop a counter relationship with the Slavic-Orthodox world: meaning primarily Russia.

Huntington develops his system by exploring edge conditions and nations that don’t fit perfectly into the civilizational cookie-cutter, Two of the most important were Russia and Ukraine:

[Huntington] devotes some time in his book to outlining the “structure” of civilisations, which he splits between “core states” (which are central to a civilisation’s identity), “member states” (which identify fully with a civilisation), cleft countries (where large internal groups belong to a different civilisation), “torn countries” (where there is a single predominant culture which places it in one civilisation but whose leaders want to shift it to another), and a few “lone countries”, which don’t fit in to any civilisation or category. Thus, Japan, China, Russia, and India are core states; Italy, Jordan, Argentina, and Belarus are member states; Ukraine, Indonesia and Kenya are cleft countries; Turkey and Mexico are torn countries; Ethiopia and Haiti are lone ones.

According to Huntington, Russia is a special case as being both a core and torn country. Huntington recounts how Russia has been for centuries torn between autocratic Slavophiles and liberal Westernizers. Up until the reign the Peter the Great, Russia (including Ukraine but not Galicia) had little to no contact with the West.

Russian civilization developed as an offspring of Byzantine civilization and then for two hundred years, from the mid-thirteenth to the mid-fifteenth centuries, Russia was under Mongol suzerainty. Russia had no or little exposure to the defining historical phenomena of Western civilization: Roman Catholicism, feudalism, the Renaissance, the Reformation, overseas expansion and colonization, the Enlightenment, and the emergence of the nation state. Seven of the eight previously identified distinctive features of Western civilization—religion, languages, separation of church and state, rule of law, social pluralism, representative bodies, individualism—were almost totally absent from the Russian experience (p. 139)

After Peter the Great came to power, he toured Europe and discovered just how backwards Russia was. He imposed many reforms, particularly on the military, and was to some extent successful in raising Russian power and competence.

In attempting to make his country modern and Western, however, Peter also reinforced Russia’s Asiatic characteristics by perfecting despotism and eliminating any potential source of social or political pluralism

<…>

At home Peter’s reforms brought some changes but his society remained hybrid: apart from a small elite, Asiatic and Byzantine ways, institutions, and beliefs predominated in Russian society and were perceived to do so by both Europeans and Russians. “Scratch a Russian,” de Maistre observed, “and you wound a Tatar.” Peter created a torn country, and during the nineteenth century Slavophiles and Westernizers jointly lamented this unhappy state and vigorously disagreed on whether to end it by becoming thoroughly Europeanized or by eliminating European influences and returning to the true soul of Russia. (p. 140)

The struggle continued through the Russian Empire. The rise of the Soviet Union created a strong synthesis of oriental despotic strongmen presiding over what was considered by many at the time as the most progressive and advanced Western ideology: Marxism.

During the Soviet years the struggle between Slavophiles and Westernizers was suspended as both Solzhenitsyns and Sakharovs challenged the communist synthesis. With the collapse of that synthesis, the debate over Russia’s true identity reemerged in full vigor. Should Russia adopt Western values, institutions, and practices, and attempt to become part of the West? Or did Russia embody a distinct Orthodox and Eurasian civilization, different from the West’s with a unique destiny to link Europe and Asia? Intellectual and political elites and the general public were seriously divided over these questions. On the one hand were the Westernizers, “cosmopolitans,” or “Atlanticists,” and on the other, the successors to the Slavophiles, variously referred to as “nationalists,” “Eurasianists,” or “ derzhavniki” (strong state supporters) (p. 142-3)

When Putin came to power he had a foot in both camps. His “statist” side pushed the importance of economic development that must form the basis of geopolitical power. He also was a Westerner and repeatedly begged the West to take Russia as a strategic partner, but under a regime of mutual respect, not as a supplicant or vassal.

Both Huntington and liberal interventionist Zbigniew Brzezinski feared in the 1990’s what today is a fixed reality. For Brzezinkski it was:

Potentially, the most dangerous scenario would be a grand coalition of China, Russia, and perhaps Iran, an 'antihegemonic' coalition united not by ideology but by complementary grievances.

For Huntington, who never imagined that most of Latin America and Africa would also join them, the great danger was the combination of Confucian (China), Islamic and Orthodox (Russian) civilizations joining forces against the West:

The solution that Huntington advances for dealing with the Eurasian dilemmas of Russia and the West involves them forming a political and military alliance against China and the Islamic civilizations. Being particularly worried about the rise of these civilizations, he recommends containment of the threat from the Confucian-Islamic states by promoting and maintaining cooperative relations with Russia. In his book, Huntington develops this point by stating that "Russia working closely with the West would provide additional counterbalance to the Confucian-Islamic connection on global issues" and that the West should "accept Russia as the core state of Orthodoxy and a major regional power with legitimate interests in the security of its southern border.”

The southern border Huntington referred to was the Caucasus Region where Russia was fighting an Islamic insurgency in Chechnya—which it turns out was fuelled and funded by the West.

Tragically, the preachers of American hegemonic universalism found in both cosmopolitan camps reacted in horror at the idea that their could ever exist zones or nations outside of the West’s reach—especially anywhere near Russia. Instead, the West nestled everywhere, settled everywhere, established connexions everywhere—and attempted to dominate everywhere. Of particular Western interest in this campaign of universal hegemony was the cleft country of Ukraine.

Cleft Country: Ukraine Riven By the West and Russia

Idealist neoconservatives continue to dogmatically push for unilateral US dominance over the globe, despite the ever-weakening US not having anywhere near the means to accomplish such a Herculean task. Having been wrong about everything for the past thirty years. neocons are still celebrated and given high office in government and prestigious positions at elite universities. With the deindustrialized West now losing a war of attrition against a global Primal Horde, realists like Huntington or Mearsheimer—who have been proven correct in many areas—are still slandered as “Putin’s poodles.” Both strongly advised against trying to pry Ukraine—an admittedly tempting prey since it was split between two civilizations—away from the Russian World.

Ukraine is a cleft country because the Galicians want to pull all of Ukraine into the West while eastern Maloross Ukrainians want to keep close ties to Russia, albeit with substantial autonomy.

The default position of Ukraine, then known as Malorossiya (Lesser Russia), from the 17th to early 20th century, was as a close but autonomous partner of Russia. Together with Belarus (White Russia) they formed a Russian World triad. Back then, Galicia, ground-zero of today’s Ukrainian nationalism, was embedded in the Hapsburg Empire. Galicians dreamed of one day ruling an independent Ukrainian state. Traditionally Galicians hated Poland and Russia in equal measures. Nicolai N. Petro in The Tragedy of Ukraine explains:

Thus, on the eve of World War I <…> a narrative had emerged that looked to Galicia as the seat of Ukrainian identity, and the best hope for Ukrainian nationhood. According to this narrative, Galicia’s historical separation from the rest of Ukraine, while unfortunate, was also in some ways fortuitous, since it had led the formation of a distinctive language, a distinctive political culture, and an exposure to Catholicism. And since the struggle to establish an independent Ukraine had emerged within the context of the struggle for Galician identity, its ultimate success had become associated with the cultural and political supremacy of Galician norms within Ukraine.

By contrast, the Maloross Ukrainian identity of Left-Bank Ukraine, with its major urban centers Kiev, Kharkov, Odessa, Dnipro, and Donetsk, saw itself as distinct from, but still complementary to Russian culture. It rejected the view that Ukraine must chose between Europe and Russia, preferring instead a partnership with both. If the modern Galician ideal is a Ukraine that can serve as Europe’s bulwark against Russia, the Malorossiyan ideal is that Ukraine can serve as a bridge between Europe and Russia. (p. 50-1)

After a brief taste of independence in the waning days of WW1, Galicia failed to achieve an independent Ukrainian homeland in the Versailles Treaty that officially ended The Great War. Instead of leading Ukraine, Galicia was placed under Polish rule. In the opening move of WW2, the Soviet Union scooped up Galicia to create a larger buffer zone in the West. As Soviet troops smashed into Poland in September 1939, Stalin’s sin of dealing with Hitler firmly planted the ideological timebomb of Galicia within the Ukraine.

Ukraine’s failure to obtain its independence in the aftermath of both World Wars led to nationalism becoming the driving political motif of Ukraine’s exiled political elites. Ukrainian nationalists managed to survive their wartime alliance with Nazi Germany by positioning themselves as allies of the West in the new Cold War against the Soviet Union. After the collapse of the USSR, they re-established themselves as regional actors in western Ukraine, and from this Galician base sought to commandeer the direction of Ukrainian politics.

Despite being a political minority within Ukraine, Galician-inspired Ukrainian nationalists have been encouraged by the West, because they can always be relied on to oppose closer ties with Russia. This, however, has deepened the split along the country’s linguistic, religious, and cultural fault lines.

The Maidan Revolt of 2014 offered a unique opportunity to deal a crushing blow to Maloross Ukrainian identity by establishing a Galician nationalist-oriented regime in Kiev. Although this regime initially had to rely on the military support of the Far Right, many pro-Maidan liberals saw this as a price worth paying to achieve final and complete independence from Russia. This marriage of convenience also suited the interests of Ukrainian nationalists, who saw their own political influence greatly magnified, as they prepared to play the long game for social and political dominance in Ukraine. (p. 247)

Since the breakup of the Soviet Union, Ukraine has evolved a division of labour among its disparate regions. Galicia, the traditional hotbed of Ukrainian nationalism, was given control over cultural and language matters. Kiev served as the center of political control, while the heavily industrialized Donbass region operated as Ukraine’s economic heartland.

It’s now a foregone conclusion that Russia will swallow up the Donbass. French President Emmanuel Macron seemed to concede the entire eastern bank of the Dnieper River to Russia. The West is stuck in a war of attrition into which its weak industrial base cannot feed enough weapons. At the same time, Ukraine is undergoing a demographic catastrophe and is running short on manpower. In all likelihood, whether it be this year or in two years, Russia will capture Odessa and create a land corridor to Transnistria in Moldova. A few thousand European troops will hardly be noticed by the now powerful Russian war machine. The zone from Kharkov to Odessa will be at least temporarily annexed to Russia. Denial of access to the sea will leave the rest of Ukraine a landlocked rump state.

Putin has on several occasions offered Galicia to Poland. Russia would consider it a strategic victory if they could hand this Chernobyl of radical Ukrainian nationalism to NATO. During World War 2, Galician paramilitaries, fighting as the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, conducted ethnic cleansing raids against Polish women and children, killing up to 120,000 civilians in what Poland today considers a genocide.

If Russia were to keep Galicia, then they would have to turn it into a gulag—a Slavic version of the Gaza Strip. This persistent thorn in the side along the frontier with NATO would be turned into an open-air prison and efforts would be made to push the unruly residents into Poland, just as Israel dreams of pushing the Palestinians into Egypt.

The leftovers of Ukraine, after the poison pill of Galicia is fed to the West, and the areas Russia annexes are subtracted, will become an economically unviable, landlocked rump Ukraine. Deprived of any ideological juice from Galicia, rump Ukraine will be forced to play its traditional role as Lesser Russia. Attitudes matters, particularly if they ever wish to export agricultural production through Russian controlled Odessa. Good behaviour will be rewarded and it is not impossible that areas annexed by Russia could eventually be handed back autonomy and the choice to return to a now well-behaved rump Ukraine. Russia does not want an economic basket case on its border either.

The Ukraine War has for the time being mended Russia. The Westernizers are now completely discredited—either in exile or keeping quiet. Eventually the same fate will befall the neoconservatives in the US, who as a group hold the lion’s share of responsibility for the US’ suddenly precarious geopolitical position.

America’s Cleft: The Clash of Woke Financialism against MAGA Industrialism

Huntington is often criticized for placing too much emphasis on civilizational issues at the expense of for example, economic cleavages. One prediction of Huntington’s that is not quite resolved is that massive Latin American immigration would create a cleft society in America. He never puts it this way but perhaps all these Mexican immigrants will serve the divisive role that Galicians do in Ukraine by trying to pull America out of the West and into the Latin American civilizational sphere?

Huntington delineates three specific threats to American national identity. As already noted, "the single most immediate and most serious challenge to America's traditional identity comes from the immense and continuing immigration from Latin America, especially from Mexico." The sheer extent of immigration and high birth rates among Latinos who share a language and religion and who are concentrated in the country's southwest region close to their country of origin means they will not assimilate like their European predecessors or Asian contemporaries. Huntington's somber worst case scenario for the future is that America will split into two de facto nations: an English-speaking "Anglo-America" and a Spanish speaking "Mexamerica" that, like Quebec in Canada, regards itself as a distinct society.

Immigration aside, identity politics and cultural relativism are a second threat, fueling a systematic assault on the "Anglo-Protestant" culture by rejecting individualism in the name of group rights. Finally, Huntington argues that declining patriotism among the leading bureaucratic, business, and intellectual elites in the United States is a challenge to the country's historic sense of its own uniqueness. The growing adherence of these groups to cosmopolitan values downplaying the significance and validity of national loyalty conflicts with the traditional patriotism of the overwhelming majority of the general public, thereby undermining political trust and cohesion

The jury is still out but certainly not in the way Huntington foresaw. The great rift in America these days is between Woke and MAGA: between financial capitalism and industrial production.

The ideological subtext of MAGA is a “retro-future” where America recaptures the cultural, political and especially economic ways of the US’ post-WW2 Glory Days of industrial capitalism. Currently the US is mired in the cultural and economic degeneracy of financial capitalism. MAGA pines for the deep cultural rootedness last experienced in the US during its heyday as an industrial giant.

While some MAGA commentators, such as Tucker Carlson, express a certain ambivalence towards capitalism, most MAGA rank and file see themselves as fighting creeping forces of communism in the US. As a result, MAGA often misrecognizes capitalist forces of disorder as communist.

In the US, it is financial and business elites, aligned with holders of inherited wealth, who are funding America’s sunset into seediness. Who wants you to eat bugs? Who wants to transition your children into eunuchs? Who drives down your wages by flooding your nation with replacement labour? Who wants you to own nothing and be happy? The World Economic Forum and other globalist oligarchs are financial capitalists.

Industrial capitalism invests liquid wealth in infrastructure and factories, seeking a high rate of profit. This process is virtuous for everyone: jobs, government services and relative prosperity are available to many. Finance capitalism arises when such bricks and mortar investments no longer make economic sense. Instead, industry is off-shored overseas. Left-over capital is deployed in speculative adventures or is used to finance the national debt. Such investments are guaranteed a fixed rate of return, but often only fund ephemeral consumption.

George Soros is an uber-financial capitalist. His 75 soft-on-crime urban prosecutors rode to power through campaign funds earned through his hedge fund’s speculative profits. For much of his long life, Soros has waged a relentless war on communism—first against the Soviet bloc and now against the Chinese. His “Open Society” means foreign countries must keep their legs wide open to US cultural, economic and military penetration. Soros may well be the GOAT (greatest of all time) anti-communist—his hatred of China and Russia knows no bounds.

A key, but not widely understood tenet of Marxism is a deep hatred towards the lumpen-proletariat. Lumpen means “ragged” in German and is a tag used to tarnish the noun it is attached to. In normal English we might say the “criminal class” or more colourfully: “hoods, hoes, tricksters and gangsters.” Marx also occasionally uses the term “lumpen-finance” to designate the parasitical class of usurers who prey on their host population with even more venom than their lower-class cousins. These are financial capitalists.

It’s possible Soros’ hatred of communism leads him to a reactionary embrace of lumpens: from Wall Street rentiers to MLK Boulevard bangers. Or there may just be a profit-motive driving his criminal crusade: drive down commercial property rates through a crime wave and then buy skyscrapers on the cheap and then flip the script by installing a tough-on-crime crusader to pump real estate valuation back towards the sky?

Increasing the crime rate does create rent extraction opportunities for financial services oligarchs. Attacking the publicly-funded (arguably socialist) police as irredeemably racist opens the opportunity of privatizing the public security business. Once the police are defunded into irrelevancy, bourgeois urbanites will have to buy subscriptions for protection against the swarming lumpen hordes. Various security start-ups will compete to provide the best private policing service. Paying extra for an Uber-Police Prime subscription may include free rape kits delivered by the heavily armed guards who are guaranteed to arrive at your residence within five minutes of the alarm being raised.

Which perhaps explains globalist outrage when El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele severely cracked down on gangbanging lumpen-proles, many radicalized in and reverse migrated from the US. Establishment media are trying to use the tired left-right binary to get conservative-leaning readers to reject Bukele’s crusade against crime as Marxist.

Much of this is unsurprising in light of the fact that Bukele and his family spent decades within the leftist FMLN. Bukele’s father was an early backer of the FMLN following its transition from a Marxist guerrilla to a legal political party following the end of the Salvadoran Civil War.

<…>

El Salvador’s recent success in combating insecurity has understandably transformed Bukele into a hero on both the regional and international right. Yet, those that celebrate the president unconditionally would do well to ask themselves whether they would do the same for Daniel Ortega’s low-crime Nicaragua.

The Daily Telegraph is indeed correct that it is kind of Marxist to crack down on lumpen-proles (and lumpen-finance). But Marxism also much prefers industrial capitalism over finance, which explains why many in MAGA see Bukele in a positive light. The article offers its readers a clear choice: remain ideologically pure by committing to the neoliberal right, but then suffer the high crime and insecurity that capitalism seems to thrive on. Or be a crypto-leftist and have safe streets. The choice is yours!

Those seeking to reinstate industrial capitalism and lower crime will be forced to breakout of the simplistic left-right binary, and start thinking more broadly about exactly which type or form of capitalism is best suited for a prosperous and safe society.

This left-right experiment in Latin America is happening in real time. As Bukele in El Salvador is waging war against parasitical lumpens, the Reaganite libertarian Javier Milei is busy in Argentina turning working people out of jobs and onto the streets in huge numbers. Eventually there will be a sharp reaction to Milei’s primitive neoliberalism and perhaps a Bukele-style strongman will come to power to clean up the mess left behind once Milei heads off to exile.

In the US, working class Latinos are increasingly rejecting financial capitalism’s cultural revolution. It turns out workers of all stripes prefer MAGA to Woke. The New York Times recently raised the alarm to their wealthy urban white readership that importing masses of people from Latin America is not exactly working out as planned:

Many Democrats have been stunned by Republicans’ inroads, as Mr. Trump has continued to unleash incendiary rhetoric about immigrants, including those from Latin America, “poisoning the blood of our country” and promised draconian policies such as mass deportations. He has advanced the Great Replacement conspiracy theory, claiming that Democrats welcome undocumented immigrants into the United States because they will allow them to vote illegally for the party.

The deepening cleft in America is not so much between civilizations, although influxes of people from conservative civilizational blocs may play a role. Social-economic class status seems to be paramount. It’s the wealthy urban areas of New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Boston which serve as America’s version of Galicia—attempting to impose a dysfunctional culture upon the masses. Upper-middle class immigrants from any civilizational background will tend to ape the cultural predilections of wealthy white Americans.

If Trump sweeps into office, riding a wave of strong support from Latino workers—wealthy urban elites may be forced to question their pro-immigration sentiments. Similar to Putin, followers of Huntington will be proven to be half correct. The demographic influx from Latin America may indeed change the current trajectory that the US is on. But where Huntington missed was on the impact of economic class.

While some may see Woke versus MAGA as a fight between democracy and authoritarianism, how can a radical minority imposing an alienating ideology upon the majority ever be considered democratic? We are seeing in real-time the catastrophe the Galicians have wrought on Ukraine. It may soon dawn on Woke, who play a similar role in the US and are in fact fanatic allies of the Galicians, that diversity is the enemy of their ideas. Only wealthy whites or those striving for such status seem to be interested in pushing “gender-affirming surgery” on youth. If MAGA succeeds in pushing and prodding America towards an industrial renaissance, many of the positive qualities that Huntington saw disappearing from America may soon return.

However, work-ethics don’t just reappear overnight. While newer immigrants may still have them, so many other American youths and adults will need to go through “work-affirming” transitions if industrialism is to ever make a comeback. With war economies and military conscription now on the agenda, perhaps the West will use the fear their loss in Ukraine will bring to fuel a cultural and economic rebound?

Amazingly well written. I'm learning so much about Ucrania and Rusia's history with your articles Kevin. I now understand better about this war.. I also found very interesting the hypotesls about civilizations clashes so I'm reading now Huntington's book .. thanks a lot for writing so well informed articles!

Plenty of whites work in crappy dangerous jobs like roughnecks or commercial fishermen. It’s just that the wages have to be high enough.