Black Sea Matters

De facto landlocked after the destruction of Odessa and other port facilities, Ukraine's counteroffensive has so far failed to threaten Crimea, but its mass drone strikes have seen some success there.

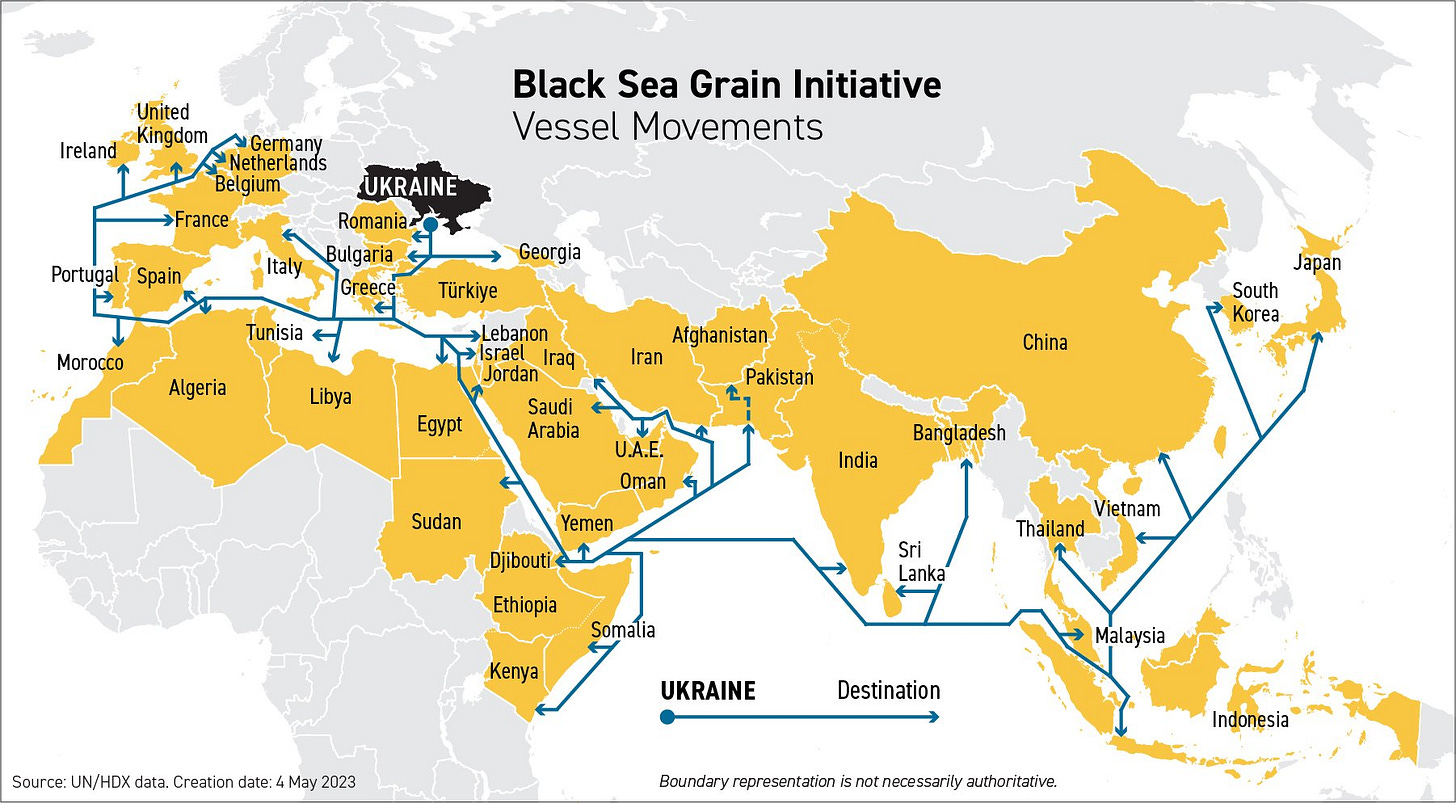

The focal point of the Ukrainian War has recently shifted from the gory trench battles in the Donbass towards the conflict’s greatest prize: the Black Sea. There are daily swarms of Ukrainian drones attacking targets on the Crimean peninsula. In three cases these drones succeeded in hitting Russian ammunition dumps. Ukrainian sea drones managed to damage Russia’s Kerch Bridge, its only land link from the Crimea to recognized Russia. Starting on July 20th, after suspending participation in the Black Sea Grain Initiative, Russia has been launching ballistic missile attacks on Ukraine’s port facilities, including grain terminals and other export infrastructure. Serious damage was inflicted all along Ukraine’s rapidly shrinking Black Sea coastline. With the US and other European allies signalling their ammunition stocks are low, and with no military industrial base to speak of for the West to replenish them, rump-Ukraine is facing a stark future as a landlocked failed-state.

This is not how it was supposed to end. The overriding strategic goal of NATO expansion into Ukraine (and Georgia) was to turn the Black Sea into a NATO-controlled lake. The key impetus to the US-backed coup d’etat in 2014 in Ukraine was to eventually gain control over the Crimean peninsula, including Sebastopol, home base to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. Conversely, the Russian invasions of Georgia in 2008, Crimea in 2014, and Ukraine in 2022 were all primarily motivated by a desire to reinforce the Russian Federation’s position along the Black Sea.

Zbigniew Brzezinski, in his 1997 work, The Grand Chessboard, explains the importance of the Black Sea from the Russian point of view :

Most troubling of all was the loss of Ukraine. The appearance of an independent Ukrainian state not only challenged all Russians to rethink the nature of their own political and ethnic identity, but it represented a vital geopolitical setback for the Russian state. The repudiation of more than three hundred years of Russian imperial history meant the loss of a potentially rich industrial and agricultural economy and of 52 million people ethnically and religiously sufficiently close to the Russians to make Russia into a truly large and confident imperial state. Ukraine's independence also deprived Russia of its dominant position on the Black Sea, where Odessa had served as Russia's vital gateway to trade with the Mediterranean and the world beyond.

<…>

Russia's loss of its dominant position on the Baltic Sea was replicated on the Black Sea not only because of Ukraine's independence but also because the newly independent Caucasian states—Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan—enhanced the opportunities for Turkey to reestablish its once-lost influence in the region. Prior to 1991, the Black Sea was the point of departure for the projection of Russian naval power into the Mediterranean. By the mid-1990s, Russia was left with a small coastal strip on the Black Sea and with an unresolved debate with Ukraine over basing rights in Crimea for the remnants of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet, while observing, with evident irritation, joint NATO-Ukrainian naval and shore-landing manoeuvres and a growing Turkish role in the Black Sea region. (p.92-3).

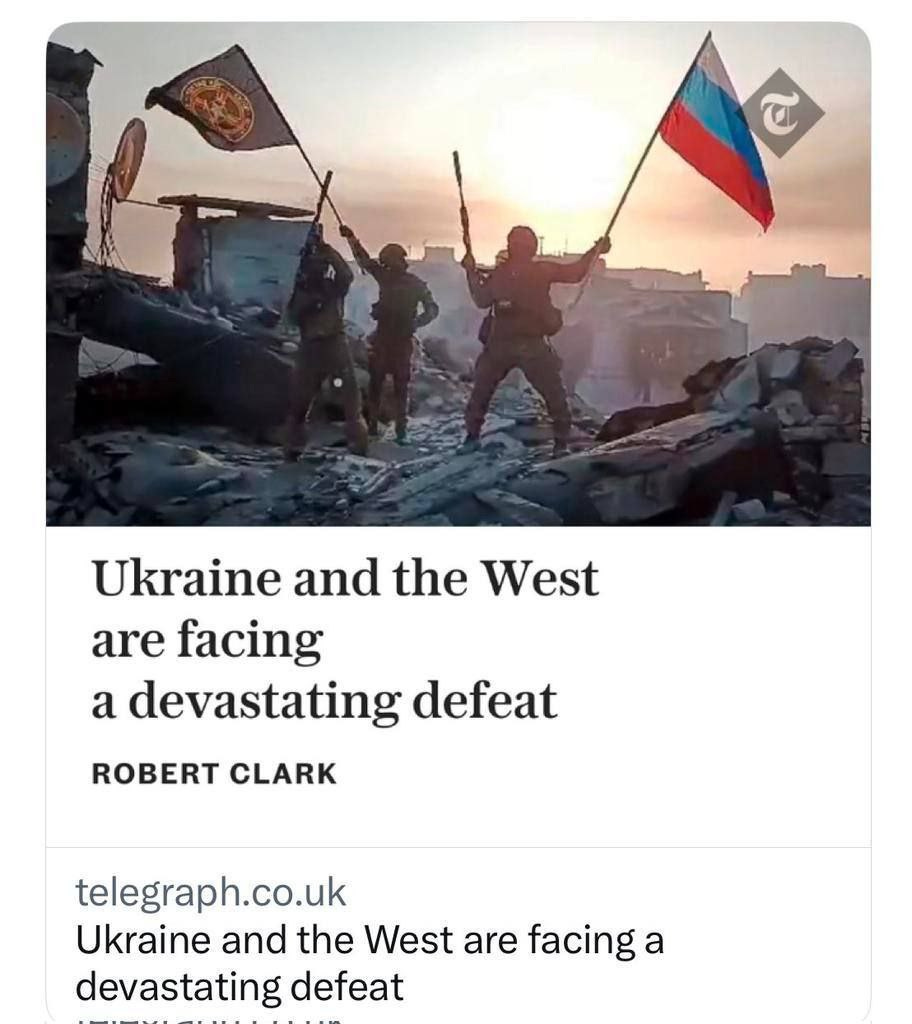

This shift of emphasis towards the Black Sea follows a disappointing NATO summit in Vilnius, Lithuania, where Ukraine was not offered NATO membership. In the runup to this summit, Ukraine launched two ruinous counteroffensives, one towards the Sea of Azov and the Crimean peninsula and another to take back Bakhmut. Both campaigns failed to achieve any serious success and left tens of thousands of Ukrainian soldiers dead or maimed. The battlefields were littered with not only Ukrainian corpses, but with expensive Western hardware. In the runup to the NATO summit, both President Joe Biden and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan pushed the narrative that the US had exhausted their ammunition stores and had little left to send to Ukraine besides cluster munitions.

Despite its high-minded moral appeals to freedom, NATO is obviously taking a balance sheet approach to Ukrainian membership. Sebastopol, home base to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, along with the rest of the Crimean peninsula and its potential reserves of natural gas, are the sort of assets that would justify NATO granting Ukraine membership. But Ukraine’s failure to recapture Crimea in its ongoing summer offensive, despite huge Western investments in arms, means these naval yards would need to be taken directly by NATO forces—a spectre far from reality. A second Ukrainian asset would be the Donbas with its 60 billion tonnes of coal reserves but again Ukraine is not making any progress in this area either. And so the Ukrainian balance sheet lacks key assets and is chock full of liabilities. With the latest moves by Russia to blockade its remaining Black Sea coastline, the Ukrainian balance sheet deteriorates further and supporting the country is increasingly becoming a millstone around its Western backers necks. As the New York Times reports:

Jens Stoltenberg, the NATO secretary general, said that the most important thing now was to ensure that his country wins the war against Russia because “unless Ukraine prevails, there is no membership to be discussed at all.” Mr. Stoltenberg said the commitments now were different from the vague promise made in 2008 that Ukraine and Georgia would someday join the alliance, without specifying how or when.

The word “prevail” is doing a lot of work in Stoltenberg’s statement. At its most expansive, to “prevail” Ukraine must retake all the land within its 1991 borders, which includes the entire Donbass and Crimea. Being able to offer this geopolitically valuable dowry to NATO would lead to a marriage of allegiances and Ukrainian membership. However, with ammunition running low, and fresh Ukrainian meat harder to corral towards the battlefields, and with NATO intervention off the table, the prospect of Ukraine “prevailing” is remote.

Inflict Pain, No Grain

It is undeniable that President Putin has done a masterful job steering the Russian economy through the Western sanctions tempest and in garnering international support from non-wealthy nations. But at times decisions that work best at the level of international grand strategy end up having negative impacts on the battlefields of Ukraine. Many Russian partisans get frustrated by such decisions as to not interdict the flows of Western weapons, not destroying the bridges over the Dnieper and the lack of an aggressive strategic bombing campaign. The very title of the action, “Special Military Operation” is powerfully detested. But this designation gives Putin wiggle room to take some unorthodox decisions.

To Russian partisans, the most incomprehensible of all Putin’s decisions was the Black Sea Grain Initiative, which allowed Ukraine to sell grain on the international markets, to smuggle in arms and store arms in its port facilities, all to compensate the globe for the wheat Russia was unable to sell due to Western sanctions.

In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, 2022, the collective West imposed sanctions on Russia, hampering her ability to export grain and fertilizers to the world. In the spring of 2022, facing a potential Russian amphibious assault on Odessa, Ukraine sloppily mined their Black Sea harbours. Many of these mines broke loose and ended up in the Black Sea proper. Wheat was not exported by ship from Ukraine due to these dangerous conditions. The West launched doomsday narratives about how poor Africans would starve due to these supposed Russian “countersanctions” against Ukrainian wheat. Of course it was the Western sanctions that were blocking exports from Russia, the third largest exporter of wheat in the world, that was most responsible for the problems.

Perhaps to help Türkiye’s President Erdogan, Putin agreed to allow Ukrainian wheat to be exported in return for the dropping of sanctions against Russian wheat. As so often happens in agreements with the West, Russia kept her side of the bargain, allowing Ukrainian wheat to be exported, but the West never completed lifting their sanctions. Ukraine naturally took advantage of this deal by using the grain corridor as a shield to launch attacks against Russian infrastructure in Crimea, and as a means of importing arms.

The key point is that in summer of 2022, Putin felt vulnerable enough to agree to the grain deal. That summer the Russian war effort reached its nadir, losing large swarths of territory in the Kharkov region as well as in Kherson. Wars are planned using a best, normal or worse case length for the war. For Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, pure speculation would posit three day best case, three month normal case, and three year worst case scenarios. After the failure of the Istanbul negotiations in late April of 2022, the Russian war machine hit a dry patch as the proper preparation for the long term scenario had not been achieved.

Wars often turn on unexpected events so predictions are always dangerous. But today, in the summer of 2023, by all appearances, Russia has turned the tide and is on track to decisively win the war by February 2025. Not only have both Ukrainian counteroffensives been ground into dust, but the Russians themselves are on the offensive up in the Kharkov region, retaking territory they lost so sloppily back in 2022. One potential point of weakness for Russia is their recent inability to protect their ammunition supplies in Crimea. Besides that though, Odessa and the rest of the Black Sea coast are now closed to Ukrainian business. The West is running out of ammunition, which in a war of attrition is fatal. With Ukraine’s failure to turn the war of attrition battlefield into a fast moving war of manouvre, they are falling back on to unconventional-style warfare of small, drone-based attacks behind enemy lines. Russia will of course label these as terrorist attacks but a less emotional view is that Ukraine is desperately trying to build up some sort of a bargaining position for the eventual peace talks, by using unconventional warfare methods.

Clustered-earth Tactics

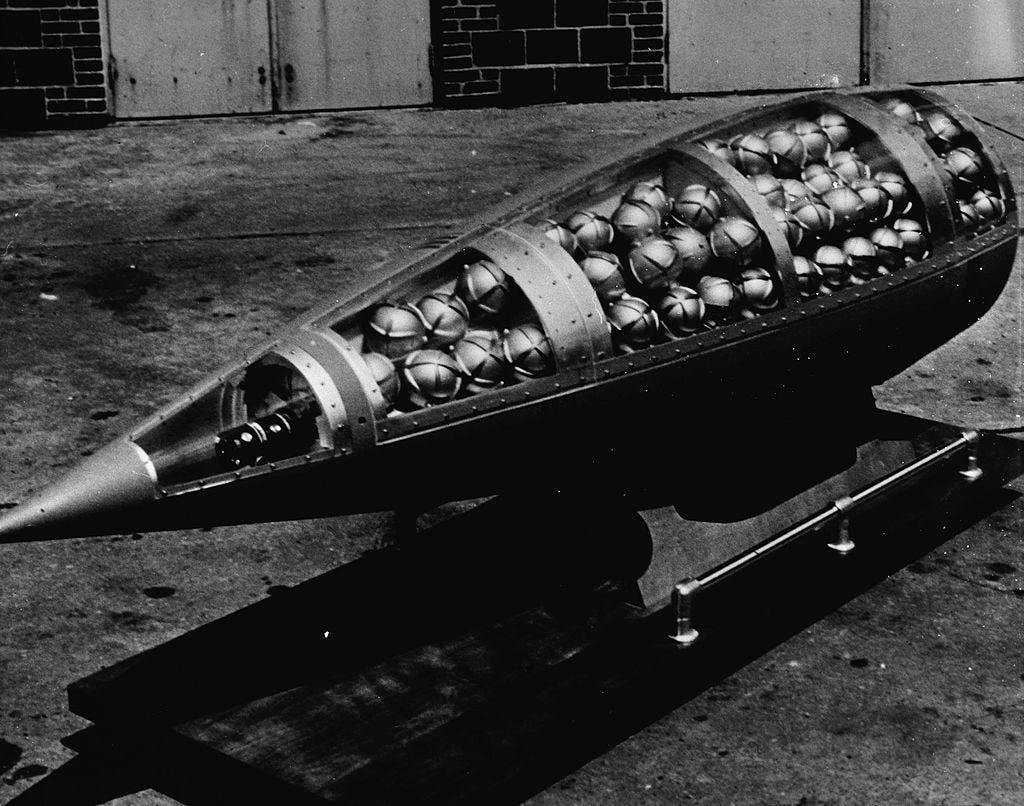

A key plank in the Rules-Based International Order (RBIO) is that the use of cluster munitions is the military equivalent of clubbing baby seals. Cluster munitions are shells or warheads that instead of having one massive charge, contain many smaller bomblets that explode over a wide area. It is similar to the difference between a single bullet and a shotgun shell, which delivers pellets across a wider area. Instead of a traditional artillery shell, which hits a single point and explodes, cluster munitions drop bomblets, the equivalent of hand grenades, across a wider area. So far so good. The concept of “humain” weapons is an oxymoron, the purpose of war is to kill opposing soldiers. The problem with cluster munitions is that they have a high “dud” rate. For whatever reason, some bomblets, which can be up to 40% of the total, end up not exploding upon hitting the ground. These unexploded “duds” then turn into the equivalent of landmines, and pose a long-term risk to civilians long after the peace treaties are signed. In Laos, a hundred civilians a year are killed by unexploded cluster munitions dropped during the Vietnam War.

After widespread use of cluster munitions by the US in Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, Serbia, Iraq, Afghanistan, by the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, and by Israel in Lebanon, the do-gooder Rules-Based International Order got to work and eventually 111 states, including most of NATO, agreed to the Convention on Cluster Munitions which banned these types of weapons. Russia and the United States, as so often happens in these matters, did not sign on to this convention. Nevertheless Russia has up to now not used cluster munitions in Ukraine, despite several attacks by Ukrainian forces using cluster munitions.

Given the widely acknowledged shortages of Western ammunition, along with Ukraine’s inability to break out of the war of attrition forced upon them by Russia, Ukraine, a signatory to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, has for more than a year been demanding to be furnished with these arms. The US recently agreed. The problem, beyond the obvious hypocrisy of breaking the Rules-based International Order, is that Russia themselves have massive stocks of much more powerful cluster munitions gathering dust, just waiting for a precedent that allows their use. Over the past days there have been reports on several Russian Telegram channels that the Russian military have started taking these munitions out of storage and are transporting them to the battlefield. Already outside of Bakhmut there is video of Russian use of cluster munitions:

The question to be posed then is why the US has taken this step, which will clearly not be in Ukraine’s interest? On the one hand providing cluster munitions is a narcissistic display of US international Caesarism—the idea that the US is a permanent state of exception, that it’s global mission is of such a lofty nature that no earth-bound norms can constrain it. While this is no doubt true, the provision of these weapons only hastens Ukraine’s downfall.

A more rational reason for providing Ukraine with cluster munitions is as a deeply cynical varient of a scorched-earth tactic. In this US clustered-earth gambit, they trick Russia into destroying the very areas Russia is likely to conquer in the coming months, forcing huge expenses in munition clearance programs for the coming decade.

In the meantime, the Ukrainian Telegram channel "Legitimny" is reporting that:

Our source reports that Western military experts are urgently advising Zelensky to withdraw the armies to the cities and conduct military operations only in the urban infrastructure, and not in the fields.

Being in the fields, even in the trenches (fox holes, etc.) is 90% death / injury from the use of cluster munitions by the enemy.

Cluster munitions are less effective in urban settings but is Ukraine really going to retreat to cities and then be sieged by Russian forces, who will indeed be out in the fields surrounding the cities, vulnerable to cluster munitions?

Another way to look at this is that the West has thrown in the towel on any victory in Ukraine and just want to expedite this war, particularly if it is true the West is dangerously low on ammunition. With a Presidential election 15 months away, the sitting US President may calculate that given American’s short attention spans, it is better to conclude the war this year than to drag it out well into an election year. And so provoking the massive use of Russian cluster munitions hastens the conclusion of the war and increases Russian occupation costs in the future.