200 Plateaus: A Globe of Nations

World-System Theory and why capitalism prefers the rise of the BRICS+ multipolar world-system in lieu of the US-led Globe of Vassals.

World-system theory (WST) combines historical, economic, political and sociological analysis under one intellectual roof. Largely a fusion of the works of Fernand Braudel and Karl Marx, its founder Immanuel Wallerstein also cites 1970’s development theory as an influence. Taking a holistic, God’s eye view of global totality, WST researches, among other things, the cycles and trends of the capitalist world-economy. Its global scope and diversity of disciplines makes WST an invaluable tool for geopolitical analysis.

WST is a return towards a unified notion of knowledge that existed in medieval times. Formerly, the search for the true, good and beautiful were all unified under the banner of philosophy. A split occurred when philosophers rebelled against the theologians, claiming rational man could find truth independent of any God. Then empiricism rose. Valuing experience and observation, it declared itself science. In doing so it banished metaphysical inductive reasoning to the realm of humanities.

The French Revolution’s claim that sovereignty resides in the people created the ideology of liberalism. Groups of experts were now needed to inform the new ruling class how best to manage this supposedly sovereign mass. Eventually three areas of knowledge emerged: economics, political “science” and sociology. Liberal ideology insisted that these three areas remain discrete from each other. These three fields fell somewhere in the middle of the science - humanities spectrum, alongside history.

World-system theory centres the globe as its “unit of analysis.” Just as a solar-system examines the rotation of planets around a sun, the world-system analyses the division of labour and interplay between nation-state component parts. WST posits a fundamental core-periphery opposition, but adds an intermediary semi-periphery component. World-system theory studies how the periphery and semi-periphery nations pivot around a dominating and hegemonic group of core nations.

In today’s context, the Collective West are core, BRICS+ are semi-peripheral and the Global South are peripheral. WST emphasizes an exploitive relationship between core and the two periphery positions. But this view is now being challenged by the rise of a multipolar BRICS+ semi-periphery. How can simple exploitation explain China’s and the BRICS+ newfound power, which is steadily eroding the core? Some mix of power transfer embedded within this exploitation must be at work in the system.

A geographic metaphor helps illustrate the current global crisis. If we add a third dimension to the core / semi-periphery / periphery diagram we end up with peaks / plateaus / plains. The third dimension represents the amount of capital (human and financial) accumulated within each component (nation-state) of the world system. What’s been happening since at least 2000 is that the BRICS+ plateau is both rising higher (accumulating more wealth) but is also expanding in two directions in plan. On the one hand it is eroding the peaks, where landslides of peak wealth are gently falling onto and raising the plateaus. On the other hand these plateaus are expanding and gently lifting the plains, particularly through Chinese infrastructure investment. If this global levelling process continues, the world-system will one day contain an interconnected nation-state system of 200 plateaus rising to various elevations.

Defining capitalism

Endless accumulation through profits is capitalism’s most fundamental axiom. But not just any sort of profits, since for thousands of years previously, local artisanal market economies around the globe were based on small and predictable profits. Capitalism, which emerged in the 15th century, requires much higher profit flows. Accumulating significant amounts of capital is only possible with super profits. But super profits are not easy to come by. And certainly not in a free market situation.

Only through quasi-monopolies built around technological breakthroughs can large amounts of capital be accumulated. An innovative capitalist drills a temporary “wormhole” through the market fabric, into a reservoir of wealth. Spurting flows of super profits are gathered into massive pools of accumulated liquid capital. However, this breakthrough has temporal limits for soon competitors appear. Many will try to drill into the same pit, and soon the once mighty wealth spigot slowly turns into a mere trickle. As the quasi-monopoly vanishes, the rate of profit declines. As the post-accumulation period approaches, the now extremely wealthy capitalist retreats into the financial realm, where money begets more money as his accumulated capital grows endlessly. As Wallerstein explains:

Since, as we have seen, quasi-monopolies exhaust themselves, what is a core-like process today will become a peripheral process tomorrow. The economic history of the modern world-system is replete with the shift, or downgrading, of products, first to semi-peripheral countries, and then to peripheral ones. If circa 1800 the production of textiles was possibly the preeminent core-like production process, by 2000 it was manifestly one of the least profitable peripheral production processes. <…> The process has been repeated with many other products. Think of steel, or automobiles, or even computers. This kind of shift has no effect on the structure of the system itself. In 2000 there were other core-like processes (e.g. aircraft production or genetic engineering) which were concentrated in a few countries. (p. 29)

Capitalism’s Gordian Knot: The Volatile Nexus of Production, Profit, and Consumption

Profits are highest when the sales price of a commodity is maximized and the cost of production is minimized. But both are constrained by the concept of effective demand: how much money do consumers have in their pockets? Raise the price too high and only a few can afford it. Lower salaries to subsistence levels and workers will be shut out of the marketplace, other than for the basic articles of survival. Various regimes of capitalist accumulation have attempted to solve this conundrum in different fashions.

As for the price of labour, during the industrial revolution, economist David Ricardo stated that:

Labour, like all other things which are purchased and sold, and which may be increased or diminished in quantity, has its natural and its market price. The natural price of labour is that price which is necessary to enable the labourers, one with another, to subsist and to perpetuate their race, without either increase or diminution.

The power of the labourer to support himself, and the family which may be necessary to keep up the number of labourers, does not depend on the quantity of money which he may receive for wages, but on the quantity of food, necessaries, and conveniences become essential to him from habit, which that money will purchase.

19th century capitalism’s workers earned starvation wages, just barely enough to restore their muscle strength and to reproduce the next generation of workers in their households. Oftentimes a wife and any child over 5 years of age worked in the factory as well. If capitalists had to pay to reproduce the next generation, the entire family should submit to surplus value extraction in the factory. Salaries at times varied by the worker’s daily caloric needs. Conspicuous consumption was reserved for wealthy classes. Otherwise the factory-produced commodities from the core were shipped to the periphery. Colonies received goods in exchange for indigenous wealth transfers back towards England.

As productive capabilities increased, a crisis of consumption ensued, triggering WW1. Henry Ford resolved the problem by combining the functions of producer and consumer into the body of the worker. His system of mass production imposed a culture of mass consumption. As salaries increased, US prosperity soared, particularly following WW2 as the spectre of Marxism from the semi-periphery Soviets forced core capitalists to increase standards of living.

This new system reached crisis in the 1970’s as so much wealth and power pooled within the working class stratum of society that profits declined. The US solved this problem through an international division of labour. Low-paid Chinese workers created commodities, indebted Americans consumed them. The Chinese helped finance American consumption by buying Treasury Bills. This was a return to the 19th century pattern where producer and consumer were disassociated.

The challenge for the 21st century will be for each nation to bring their production and consumption into rough balance. The current geopolitical tensions between China and the US will inevitably lead to more Chinese consumption, which leads to less for Americans. Lowering consumption can happen quickly, while increasing production capabilities takes investments and years to develop. The coming decline in US consumption will be felt as “degrowth” and a lowering of the standard of living. But given the job losses that Artificial Intelligence may wreak on the professional classes, this decline may be felt strongest in the upper-middle class stratum of US society. The working class was already decimated decades ago by globalization.

Hegemonic Slash and Churn: Regimes of Accumulation

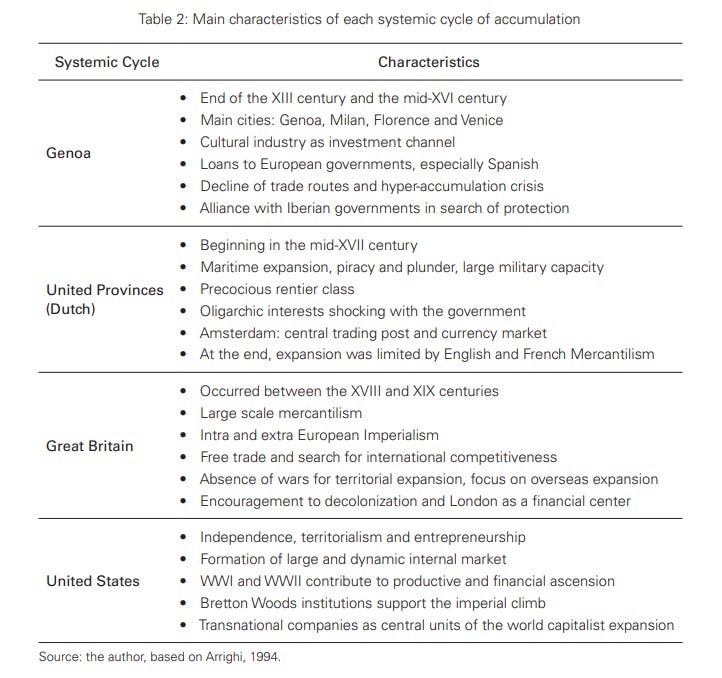

The core of the capitalist world-system is dominated by one leading nation-state. With the advent of each cycle, the new hegemon’s increasingly large size and innovative solutions to the previous era’s crisis help advance the capitalist world-economy. Since the dawn of capitalism in the 15th century there have been four cycles of capitalist accumulation. Giovanni Arrighi, a scholar closely associated with WST explains:

we can identify four systemic cycles of accumulation: a Genoese-Iberian cycle, stretching from the fifteenth through the early seventeenth centuries; a Dutch cycle, stretching from the late sixteenth through the late eighteenth centuries; a British cycle, stretching from the mid eighteenth through to the early twentieth centuries; and a US cycle, stretching from the late nineteenth through the current phase of financial expansion. Each cycle is named after (and defined by) the particular complex of governmental and business agencies that led the world capitalist system, first towards the material and then towards the financial expansions that jointly constitute the cycle. The strategies and structures through which these leading agencies have promoted, organized, and regulated the expansion or the restructuring of the world capitalist system is what we shall understand by ‘regime of accumulation’ on a world scale

Just as there are two phases in the profit-life of an innovative commodity, each capitalist hegemony goes through a two-stage cycle of capitalist accumulation. First occurs a material productive stage, where new systemic structures lead to large profits. But at some point other competitive nation-states arise within the semi-periphery, and inevitably the rate of profit starts to drop within the hegemonic core nation.

A period of financialization follows. Core-nation capital turns liquid by shuttering factories. One pool of capital seeks to have their money beget more money through financial speculation. Another pool scans the semi-periphery, where labour and raw materials are cheap, for investment opportunities. Cosmopolitan capital seeks the highest rate of return by fleeing the constrictions of its core nation-state container. What inevitably happens is that these capital inflows finance the rise of the next epicentre of capitalist power. This budding hegemon’s material expansion cycle overlaps with the fading hegemon’s financial cycle:

These cycles and episodes can only be definitively identified in hindsight. In the chart above, if the curve on the left represents the Dutch cycle, the curve in the middle the British, and the curve to its right the American, a fourth Chinese speculative material expansion is shown in a solid black line to the right of the graph. Arrighi, in his book from 2009 Adam Smith in Beijing, proclaimed China as the rising fifth global capitalist hegemon. China’s rise during the following 14 years have only reinforced this notion.

Looking back today, the US started challenging for stewardship of the capitalist world-system in the early 20th century. A period of extreme turbulence ensued, as global relations adjusted to the new power reality. After two world wars separated by a global depression, the US enjoyed 30 years of capitalist prosperity and splendour. This prosperity was amplified by the Cold War and the West’s need for conspicuous displays of a high standard of living to curb the Marxist challenge. The zenith of this prosperity was reached around 1968, when corporate industrial profits peaked. A decline ensued and progressively production was replaced by a decadent financialization--a period of which we are in the final palliative stages. During this financialization cycle, mobile capital fled the US and set up shop in China. Today we are in a strange epoch where a global division of labour is still prevalent. Impoverished and obedient workers in China produce commodities for obese and self-obsessed American consumers. At first Wall Street tapped into these huge arteries of cash flow. But increasingly China through its Belt and Road initiative wants to dominate trade infrastructure and keep for themselves that precious surplus value extracted from their workers.

Globe of Nations or a Globe of Vassals?

William McNeill in his introduction to The Rise of the West posits four historic civilizations on the Eurasian landmass: From west to east they are the Greeks on the Aegean Sea, the Middle Eastern on the Persian gulf, the Indus and Ganges valleys of India and the Chinese highlands. These four civilizations are in a perpetual state of rising and declining in relation to each other:

Civilizations may be likened to mountain ranges, rising through aeons of geologic time, only to have the forces of erosion slowly but ineluctably nibble them down to the level of their surroundings. Within the far shorter time span of human history, civilizations, too, are liable to erosion as the special constellation of circumstances which provoked their rise passes away, while neighboring peoples lift themselves to new cultural heights by borrowing from or otherwise reacting to the civilized achievement. (p. 249)

Western Europe is the progeny of ancient Greek civilization. It created the capitalist world-economy and as a group rode this innovation to considerable heights of wealth and technological prowess. The progression of capitalist hegemons, from Northern Italy, to the Netherlands, Britain, and the United States form a metaphorical ridge of increasingly higher peaks of accumulated wealth and power, and today constitute the core of the capitalist world-system.

With China’s rise to the heights of industrial material power, will the linear growth of the system continue? Will the quantitative progression of capitalist hegemons Genoa—Dutch—UK—US be continued with the addition of China replacing the US as unipolar epicentre of the capitalist core?

Alternatively, is the rise of a multipolar BRICS+ plateau of semi-peripheral nation-states a sign that the capitalist world-system is in such a crisis that only a qualitative shift will allow continued regimes of accumulation? From Wallerstein:

True crises are those difficulties that cannot be resolved within the framework of the system, but instead can be overcome only by going outside of and beyond the historical system of which the difficulties are a part. To use the technical language of natural science, what happens is that the system bifurcates, that is, finds that its basic equations can be solved in two quite different ways. We can translate this into everyday language by saying that the system is faced with two alternative solutions for its crisis, both of which are intrinsically possible. In effect, the members of the system collectively are called upon to make a historical choice about which of the alternative paths will be followed, that is, what kind of new system will be constructed. (p. 77)

And today, Wallerstein’s prophetic words are becoming reality as the rise of the BRICS+ order provides the world with a second equation for nation-states to plug into: a Globe of Nations in lieu of the US-led Globe of Vassals.

The process of bifurcating is chaotic, which means that every small action during this period is likely to have significant consequences. We observe that under these conditions, the system tends to oscillate wildly. But eventually it leans in one direction. (P.77)

Bifurcation creates the geopolitical churn that President Xi recently remarked on not having occurred for a hundred years. Reverberations caused by US sanctions are now oscillating wildly within the world-system and pushing the US dollar off its throne. From a policy point of view, the last thing a rickety hegemon wants to do in these situations is rock the metaphorical world-system boat.

Within Wallerstein’s concept of a world-system, there are two structural types. One variety is a “world-empire”, which pursues a globe united under a common political system. The other is a “world-economy” a regime that values a diversity of independent political units held together by economic links.

Wallerstein explains that pre-modern economic systems were unstable and liable to conquest by empires. He gives China, Egypt and Rome as examples. But a qualitative shift takes place with the advent of capitalism, which favours a single division of labour but with “multiple polities and cultures.” He points out that “the so-called nineteenth-century empires, such as Great Britain and France, were not world-empires at all, but nation-states with colonial appendages operating within the framework of a world economy.” (p. 6)

For most of its reign, the long 20th century US-led system was unambiguously a world-economy. However, since the advent of the US “unipolar moment,” there has been an increasing drive to establish a world-empire based on liberal democracy and free market capitalism under American unipolar leadership. The most glaring example was the “declaration of empire” in Francis Fukuyama’s triumphalist The End of History and the Last Man where he broke the news to the world that There Is No Alterative to the American political system. Mere words were followed by actions when a democracy crusade was launched in the Middle East. Eventually the globe was split into good and evil: democracies and authoritarians. The concept of “human rights” became a weapon against nonconformist states. This global ideological breach incited creeping expansion towards Russia and threats against China. This campaign for global political conformity was camouflaged and promoted by cultural campaigns for identity diversity. As Wallerstein emphasizes, capitalism abhors a systemic empire and prefers churning such hegemons into the soil. Through the magic of creative destruction, new world-systems of capitalist accumulation start to blossom from the manure of the former regime.

200 Plateaus

200 Plateaus, the creation of a Globe of Nations entails China renouncing unipolar power, and in a qualitative shift, leading a peak-levelling world-systemic new regime. By rejecting the peak, the Chinese-led multipolar BRICS+ "plateau" will be incited to spread. Expansion towards the existing peaks (The West) will cause wealth erosion. Degrowth will occur due to the diminishment of dollar power, and will provoke landslides of accumulated US capital rushing onto the plateaus. In turn, as the BRICS+ make massive infrastructure investments in the Global South, the “plains” will modestly rise. In such a dispersed multipolar array, some plateaus will certainly be higher than others, but a general levelling of national prosperity will occur across the globe. China will no doubt emerge one day as the highest plateau. And the temptation for future generations of Chinese leaders to turn unipolar will always linger.

The West can cut their losses, accept the the core / semi-periphery / periphery game is finished and concentrate on becoming high-performance plateaus. This means not wasting accumulated capital on wars and on futile sanctions aimed at maintaining the failing Globe of Vassals system. For Europe this will be much easier, as their production and consumption is already in rough balance as a whole, although persistent north - south disparities remain to be solved.

China’s power will increase as it becomes the largest holder of investable liquid capital. A key feature of the capitalist world-system, as noted by Max Weber, is the interstate competition for mobile capital. This may explain Emmanuel Macron’s recent conversion to the Group of Nations concept.

Capitalism thrives on creative destruction on all levels. The system churns open “wormholes” of super profit opportunities. However, capitalism has always had a love-hate relationship with the nation-state. It relies on the state above all to help protect quasi-monopoly positions. Once locked into a Globe of Nations regime, capitalism will feel the antagonism of state intervention when trying to steer those gushing capital flows exclusively into private channels.

The capitalist interest group par excellence, the World Economic Forum (WEC) has been strangely quiet over the past year. WEC had already predicted that: “America’s dominance is over. By 2030, we'll have a handful of global powers:”

The world's political landscape in 2030 will look considerably different to the present one. Nation states will remain the central players. There will be no single hegemonic force but instead a handful of countries – the U.S., Russia, China, Germany, India and Japan chief among them – exhibiting semi-imperial tendencies.

<….>

Nation states are making a comeback. The largest ones are busily expanding their global reach even as they shore-up their territorial and digital borders.

The coming WEC struggles to co-opt the BRICS+ will animate the 2030’s.