On a Giant's Shoulders

Macron's destiny and de Gaulle's precedents ricochet and criss-cross the present crisis. Pursuing the General's geopolitical vision will guide France towards the rising multipolar order.

Mark Twain’s aphorism, “history doesn’t repeat itself, it rhymes” is an injunction to hold precious erstwhile verses of times gone by. Western culture compels a laser focus on the present, where the lyrics of current events float barren of context, unable to resonate with those of the past.

Recently, Emmanuel Macron seemingly declared independence from the unipolar order following his summit with China’s President Xi. A look back at the diplomatic manoeuvrings of Charles de Gaulle brings many pleasant accords with Macron’s recent measures.

Dissonance, nonetheless, is total between the two men in the realm of achievement. De Gaulle was one of the most extraordinary men of the 20th century, building his reputation on four pillars of success. Macron’s only trifling twig of notoriety was moulding himself into a pillar of the establishment while employed at a Rothschild’s bank. Following years of lacklustre feats of presidential mediocrity, Macron shocked the world by suddenly throwing in his lot with the Chinese-led multipolar order. If this is indeed Macron’s intention, he has the shoulders of a giant past to stand upon.

Theory and Praxis

Charles de Gaulle’s first pillar of success was earned as an avant-garde military theorist. In the decades before WW2, in parallel with Britain’s Basil Liddell-Hart and Germany’s Heinz Guderian, de Gaulle theorized mobile mechanized warfare. His prophetic 1934 book, Towards a Professional Army, foretold the rising danger in Germany. Alistair Horne, in his book To Lose a Battle: France 1940, quotes de Gaulle:

‘Nowadays, Germany is ceaselessly marshalling the means at her disposal with a view to rapid invasion.’ To meet this menace, ‘A certain portion of our own troops must always be on the alert and capable of deploying its whole force at the first shock of attack.’ An inert, passively defensive Army, de Gaulle scornfully predicted, would be ‘surprised, immobilized and outflanked…’ He heaped derision on France’s conscript Army with its ‘provisional groupings’, which, ‘once dispersed, are re-united with difficulty, like a pack of cards continuously shuffled and mixed up’. The only hope for France, de Gaulle considered, lay in mobility – ‘it is therefore in manoeuvring that France is protected’ – and such mobile striking power could only be obtained by an efficient professional Army mounted on tracks.

Tragically, his elders on the French General Staff rejected his pleas for mobility in favour of static defence fortresses such as the Maginot Line. The British military likewise dismissed the genius of Liddell-Hart. In contrast, Germany’s new ruling elite saw their own youthful vitality reflected in the ideas of both theorists. Hitler and Albert Speer appreciated de Gaulle’s book and claimed to have read it several times. With Guderian’s inclusion of close air support, the concept of Blitzkrieg bloomed.

De Gaulle’s futile crusade against the geriatric French military hierarchy marked a pattern of brilliance and bravery that would define the rest of his life. As Alistair Horne proclaims, “nevertheless, the real significance of de Gaulle and his pre-war writings was that, for France at that time, his views were as outstanding as his courage in stating them.”

De Gaulle’s second pillar was earned serving as a battle-hardened officer leading men in war. When the Germans launched their invasion of France in May, 1940, the then Colonel de Gaulle turned down a safe political appointment and took command of the ragtag Fourth Armoured Division. Assembling the broken pieces, he led a brave and briefly successful assault on Montcornet. But it was too little too late. France fell to Germany a month later. His ideas and execution helped lay the groundwork for armoured manoeuvre warfare. If Ukraine launches an offensive towards the Crimea, they will be incorporating many of de Gaulle’s innovations.

His third pillar, de Gaulle’s leadership of the Free French movement during WW2, is renowned. After France regained her sovereignty in 1944, de Gaulle struggled to mould the emerging Fourth Republic’s political institutions. His desire for a strong executive was thwarted by partisan bickering. In 1946, he dramatically retired to the tranquillity of his manor in Colombey-les-Deux-Églises and began writing his memoires. Decolonization was sweeping the globe following WW2. Perhaps de Gaulle understood that the next several years would be traumatic as France’s imperial domains were about to vanish, one after another?

War in Algeria

Seized in 1830, Algeria was the jewel of France’s colonial possessions. Its coastal areas were annexed into France-proper in 1848. After WW2, independence pressures mounted as European colonial regimes collapsed world-wide. In 1954, France was ousted from Vietnam (Indochine) after a humiliating defeat at Dien Bien Phu. Later that year, perhaps roused by France’s waning aura of invincibility, the Front de libération nationale (FLN) launched a war to wrest control of Algeria back from the French.

The political left, the dominant force in France, was split by the war. In 1957, philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre attacked the French Communist Party (PCF) for its tacit support of the French war effort. The PCF had a long history of colonial ambivalence. Confident that they would soon grasp power, the PCF wanted to rule as large a Red France as possible in its quest to steer the proletariat towards the promised land:

In the 1930s the party could conceive of no other salvation for colonial peoples than union with French democracy against the overriding threat of (racist) fascism. In the immediate post-war era, during its participation in power, the party endorsed the Constitution of the Fourth Republic and of the French Union, the aim of which it never ceased to characterize as the preparation of colonial peoples, under French tutelage, for eventual autonomy within the framework of Union fraternelle, librement consenti. [brotherly union, freely consented] The party had always recognized the right of all peoples to self-determination, but the right to divorce, it never tired of repeating, was not the obligation to divorce; in no sense was eventual separation from France seen as a normal solution, on the contrary common sense dictated that France and her overseas territories always remain linked by 'common questions, posed by history', only soluble within a framework of continued association of an economic, social, cultural and political kind.

“Brotherly union, freely consented” may be an apt slogan for the gathering BRICS+ association. But during post-WW2 decolonization, this idea was premature. These underdeveloped nations had to first break away from their colonial masters before any voluntary process of reconnecting global bonds could begin.

In 1956, a center-left coalition dubbed the Front républicain won the legislative elections on the promise of negotiated peace and eventual independence for Algeria. Headed by Prime Minster Guy Mollet, France proceeded to dismantle the more traditional colonial structures in Tunisia and Morocco. Algeria was different because of its three départements, which in theory were just as French as the Rhône or Calvados. In a stance that rhymes with the present day, Mollet insisted negotiations with the Algerian insurgents (FLN) could only begin once they had been defeated.

And defeated the FLN were, time and time again! As documented in the film, The Battle of Algiers, France went on to win numerous battles deploying torture squads and death camps. But as happens so often in struggles against insurgencies, each “victorious” battle paradoxically brought France one step closer to defeat. As events took an increasingly ugly turn, the United States and Britain haughtily offered to undertake a “good offices” [bons offices] mission to bring France and Algeria to the negotiating table. Today, it is China making similarly disingenuous offers to lead diplomatic efforts to end the war in Ukraine.

By the beginning of May, 1958, the French military in Algeria was growing increasingly paranoid. From Alistair Horne’s celebrated, A Savage War of Peace:

. . . . Thus, in Algeria, the senior French army commanders, under pressure from foreground events, were constantly blinkered to higher realities; to the state of the war in the international, political arena, or, later, to public opinion at home. By the spring of 1958, however, they could deduce with the most clear-cut conviction that they were winning the immediate shooting war on all fronts—and for the first time since November 1954. The Battle of Algiers, Agounennda, Souk-Ahras, the blocking of the barrier-runners on the Moroccan frontier as on the Tunisian, the new successes in the underground war; every sign vindicated this conviction. Yet, at the same time, more thoughtful senior officers felt menaced also by a mounting and harrowing sense of urgency. Was this perhaps the last moment when a military victory could be exploited? How long would it be before the flow of weapons from the Communist bloc, and possibly more direct means of support, might reverse the tide? The smell of victory was strong, but there was also, coupled with it, a nasty smell of negotiations in the air; the bons offices episode and other indications all pointed to this. And negotiations implied surrender. Were the politicians getting ready to sell the army down the river once again? The memories of the Third Republic and 1940, of Dien Bien Phu . . . . were always too close for comfort.

The French Army launched an insurrection in Algiers in May 1958. Rioters blocked the route of the latest governing official sent from the mainland. Emotions escalated, and in Paris, the feeble government dissipated into the air. Rumours swirled that French paratroopers were already in place in the capital ready to seize power in a military coup d'état. France, already in the middle of a bitter civil war in all but name, suddenly found herself without a government. Would the generals from Algeria install a military junta with one and only one goal in mind, victory in Algeria? This entire episode is largely forgotten today, but Horne, writing 20 years after the events, puts the chaos in its proper historical context:

In terms of the broad canvas of French affairs, the mad May days of 1958 seem to belong to a long past era: to the storming of the Bastille, to the revolutionary scenes of 1830 and 1848, to the tragi-comic extravaganzas of the Commune of 1871, rather than to contemporary history less than two decades old.

Fourth Pillar: From Coup d'état to 5th Republic

After walking away from politics in 1946, de Gaulle receded from the French public’s consciousness. But as turmoil spewed out of Algeria, many called on this benevolent father-figure to again play the role of national saviour. France’s collective yearning for de Gaulle, transposed to an American context, is best captured in the lyrics of Simon and Garfunkel’s Mrs. Robinson:

Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio?

Our nation turns its lonely eyes to you

De Gaulle played his cards with cunning. He waited and did nothing, letting the tension build. As the tempo of pleas for him to grab power and rescue France accelerated, he rebuffed them with humour: “Why do you want me, at 67 years of age, to start a new career as a dictator?”

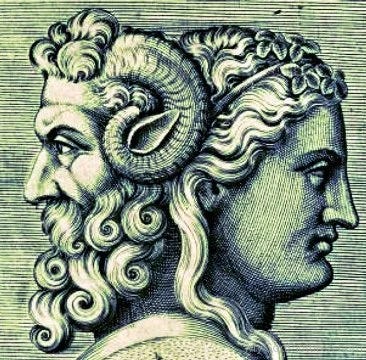

Only once assured that everyone would bow to his will did de Gaulle take the leap. From a balcony in Algiers, de Gaulle accepted power with words steeped in ambiguity: “Je vous ai compris” [I understand you]. His Janus-faced rhetoric turned his personage into a hazy mirror, where the various factions optimistically imagined their own positions were being reflected.

De Gaulle urgently built an institutionally stable 5th Republic, headed by a dominating President—armed with the kind of authority a general might wish for. Today, Macron has inherited these powerful political dispositions in a slightly watered-down form.

Only once de Gaulle had crafted his 5th Republic into a secure political bastion did his fuzzy visages bolt into a commander’s sly leer. He brutally stabbed the Generals in the back by renouncing France’s sovereignty over Algeria. Over the preceding years, de Gaulle could not have missed noticing that Germany, freed of any foreign policy ambitions, was investing in productive infrastructure while France was throwing wealth away in a futile attempt to hold her empire together. De Gaulle announced to the world that French colonisation was a thing of the past: “Decolonisation is our interest and, therefore, our policy. Why should we remain caught up in colonisations that are costly, bloody and without end, when our own country needs to be renewed from top to bottom?” This treasonous statement launched a second coup d'état attempt, the General’s Putsch in Algeria. Whereas de Gaulle had expertly surfed the first insurrection to power, he ridiculed and then quashed this second uprising by deploying his newly acquired Presidential authority to hunt down and eventually arrest all the conspirators.

Did Macron come to a similar conclusion regarding the US-led unipolar order as de Gaulle did on colonialism? By seemingly throwing in his lot with China, Macron may soon try aligning with the rising BRICS+ tide, an order into which present-day Algeria is set to take a privileged place. Ironically then, Algeria may soon hold veto power over their former colonial French masters in their relationship with BRICS+.

Volodymyr Zelensky grasps these Algerian precedents. They drive his insistent refusal to negotiate with Russia, fearing renegade battalions may try to grab power. By thrusting the Ukrainian armed forces into continuous defeats, he is depleting their fighting morale to the point where eventually the dead-enders among them will demand negotiations or die.

Tragedy fades to farce

One of Karl Marx’s most cited quotes is, “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” In Marx’s story, the tragedy refers to the world-historical giant Napoleon Bonaparte and the farce to his absurd imitation, Napoleon III.

This sequence fits equally well for Charles de Gaulle and his pale imitation, Emmanuel Macron. Psychologically, de Gaulle was driven to reject the dominant paradigm and to fight to fix it. This courage to challenge power required not only the foresight to deduce future doom, but also the mental agility to glean keen policy solutions from the past.

Macron, at least up until his landing in Beijing, had manically embedded himself into the failing social power structure. Taking his orders from above, Macron imposed them with relish on those below. It’s no great feat of brain power to cling on to the establishment rails that have predefined a path towards debacle.

The tragedy of de Gaulle was his failure to impose his superior visions, while the farce of Macron is, up until recently, his meek submission to the status quo.

Nevertheless, as only Nixon could go to Red China thanks to decades of building anti-Communist political capital, perhaps only a pillar of the establishment like Macron can go to Beijing and help overturn the unipolar world?

Keeping the Jackals at Bay

The tragedy-farce sequence is reversed in the political violence targeting Charles de Gaulle and JFK. The farcical failure to kill de Gaulle in 1962 preceded the tragic assassination of Kennedy in 1963. In both cases, the violence was motivated by the loss of colonial possessions to the enemy.

The Algerian generals reacted to de Gaulle’s betrayal by conjuring the OAS, [Organisation armée secrète] a sort of Azov Battalion avant la lettre. The OAS launched a reign of terror in response to de Gaulle’s peace deal with the FLN. The Évian Accords delineated a path towards Algerian independence. One branch of the OAS carried out a series of terrorist attacks in Algeria after the ceasefire was agreed. The goal was to provoke an FLN reaction, which it was hoped would then damage the peace process.

Another branch conducted a campaign of political violence in France. Plastic explosives ravaged Jean-Paul Sartre’s flat twice. The OAS are most notorious for their several plots to kill Charles de Gaulle, in revenge for “losing Algeria.” Their failed assassination attempt on de Gaulle and his wife at Le Petit-Clamart, a southern suburb of Paris, was re-enacted in the opening scenes of the film “The Day of the Jackal,” based on Frederick Forsyth’s 1971 novel of the same name. The film’s plot dramatized a fictional follow-up OAS assassination scheme targeting de Gaulle.

Feelings of betrayal at the loss of Cuba link the de Gaulle assassination attempt and the successful JFK killing. The failed Bay of Pigs invasion provoked OAS-like reactions within the rogue anti-communist factions of the intelligence community and among groups of militant anti-Castro Cubans.

Lee Harvey Oswald was either a sure-shot Marxist-Leninist assassin or a duped deep-state patsy depending on the observers point of view. Oswald projected two conflicting Janus-faced readings of being either a pro-Castro militant or an anti-Castro agent provocateur. These sort of true essence arguments are today replicated after each mass shooting atrocity, as partisans search the presumed assailant’s social media for tell-tale signals—such as pronouns in a bio or photos featuring a red MAGA hat—of partisan affiliation.

The New York Times presented their own Janus-faced reading of the JFK assassination. Steadfastly defending the Warren Commission narrative that a disgruntled Communist loser was alone responsible for killing JFK, the NYT simultaneously implicated right wing political enemies:

In the early 1960s, a small but vocal subset of the Dallas power structure turned the political climate toxic, inciting a right-wing hysteria that led to attacks on visiting public figures.

<…>

The extremism in Dallas in 1963 still thrives in Texas today, though less so in Dallas itself. Back then, commentators on the radio program sponsored by the oil baron H. L. Hunt said that under Kennedy, firearms would be outlawed so people would not “have the weapons with which to rise up against their oppressors.”

A similar ambivalence is expressed by the NYT’s desire to blame the Nord Stream pipelines explosions on Russia while also pushing the official narrative that of a group of pro-Ukrainian “lone nuts” were responsible for the terrorist attack. In both cases—JFK and Nord Stream—a more obvious third option is shrouded behind the emotions of partisan strife.

OAS Ukrainian-style?

Alistair Horne’s Algerian War masterpiece, A Savage War of Peace, is a favourite among military intellectuals, particularly those specializing in wars of insurgency. Primarily a historian of France, Horne’s advantage was that as a foreigner, he was above the tribal tribulations that so swayed the visions of natives immersed in the political tensions of France.

George W. Bush met with Horne at the White House—unfortunately too late since he had already launched the Iraq War. Other heads of state recognized the value of Horne’s works:

Former Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon said that "A Savage War of Peace" was his favorite bedside reading, and that one of Horne's earlier books, "To Lose a Battle: France 1940," helped him win the 1973 October War against Egypt.

The lessons from Algeria may not be well understood by the general public but policy makers will be well aware of the risks. In addition to Horne’s book, the film, “The Battle of Algiers has been used as a training film by organisations ranging from the Black Panthers to the Department of Defense.”

It is likely that fear of an OAS-style Azov terror campaign, following any eventual defeat in Ukraine, is driving EU optics of conspicuous provision of weapons to Ukraine. Not wanting to be the proverbial only house on the street not displaying a burglar alarm box, European governments are clambering to dissuade future Azov terrorists from targeting their cities. With refugees penetrating across Europe, a “stab in the back” reaction could be triggered by other governments pushing peace negotiations. Dissident networks could be activated, armed with Western weapons that never quite made it to the Ukrainian Army. Fighting milquetoast European police forces would be a welcome respite from relentless Russian artillery barrages for Azov-type militants.

Premature Recognition

In January of 1964, Charles de Gaulle angered Washington DC by his then radical act of recognizing Red China and agreeing to the One-China policy. This transpired more than five years before Nixon made his own opening to China. Just as today with Macron’s recognition of China’s global power, howls of Western furore were the response to de Gaulle’s ploy.

Both de Gaulle and Mao were chafing under the yoke of the then bipolar global order. France and China yearned to break free from the fetters placed on them by the dominate powers of each bloc, the US and the USSR. This desire for national sovereignty was expressed in de Gaulle’s conception of European integration: L'europe des patries [Europe of Nations].

De Gaulle’s vision was a “friends with benefits” array of international intercourse between nations. This framework would unshackle France from simply being one of many in the harem of a US-led alliance. Henry Kissinger in Diplomacy preferred a different analogy to illustrate the US view of ally relations:

Because Washington took uniformity of interests among the members of the Western alliance for granted, it treated consultation as the cure-all for every disagreement. In the American view, an alliance was like a publicly held corporation, influence within it was deemed to reflect each party’s proportional share of ownership, and should be calculated in direct proportion to a nation’s material contribution to the common effort. (p. 603)

Nearly 60 years later, de Gaulle’s principle of a voluntary collaboration between sovereign nations is the guiding philosophy of the BRICS+ multipolar global order. As de Gaulle’s biographer, Paul-Marie de la Gorce noted:

During that year [1963] de Gaulle did never stop paying attention to the deep trends which perhaps were going to transform the condition of the world . . . . For five years he has been announcing the coming of China to the rank of powerful and independent states; nothing will prevent this from taking place anyhow, nor will anything prevent the multitudes of Latin America from contesting the North American hegemony. The Soviet hegemony is already being contested in several East European countries. Immense transformations will inevitably take place in Africa and Southeast Asia. Hence, is it not in the French interest and thereby in the European interest to foresee these forthcoming changes and to plan one’s game in the prospect of a completely new chessboard? (p. 734)

Driven by the catalyst of Ukraine, a new multipolar BRICS+ reality is sweeping the global chessboard, bringing de Gaulle’s ideas to concrete form.

Baby Brexit in the Crib

Victor Hugo asked, “What is history? An echo of the past in the future; a reflection from the future on the past.” As the plane of the present relentlessly flickers forward, the past and future ricochet through, splattering their patterns on each frozen frame of present time.

Two years after Charles de Gaulle recognized Communist China, he touched down in Moscow, promising an era of "la détente, l'entente et la coopération” [relaxation of tension, understanding and cooperation]. Although de Gaulle had been a harsh anti-Communist, in Moscow he advocated for a united Europe of Nations from the Atlantic to the Urals. De Gaulle’s rather optimistic understanding was that France would be the first among equals within this group of European nations. His strategic intent was to break the bipolar monopoly of power invested in the USA and USSR. More broadly, de Gaulle hoped that France would paradoxically lead a non-aligned alliance of nations who sought to avoid the superpower duopoly.

As Britain repeatedly applied to join the budding seven-nation European Economic Community (ECC), the precursor to today’s EU, de Gaulle feared they were a stalking horse for American domination of Europe. De Gaulle strived to avoid the dependency that today Europe finds itself in by relying on the United States for defence. As Kissinger explains in Diplomacy:

Single-minded devotion to the French national interest shaped de Gaulle’s aloof and uncompromising style of diplomacy. Whereas American leaders stressed partnership, de Gaulle emphasized the responsibility of states to look after their own security. Whereas Washington wanted to assign a portion of the overall task to each member of the alliance, de Gaulle believed that such a division of labor would relegate France to a subordinate role and destroy France’s sense of identity. (p. 604)

There was a certain ambiguity in de Gaulle’s Atlantic to Urals vision. Did this club include Britain, which only has a small Atlantic coastline in Cornwall? As much difficulty as France would have keeping an upper hand on Germany, letting Britain join the club was a bridge too far.

And so when Britain subsequently applied to join the EEC, de Gaulle said non, thus killing baby Brexit in the crib. But as the future ricochets with the past, a decade later, de Gaulle’s successor, Georges Pompidou chose a policy of “Brentrance.” Given a new lease on life, baby Brexit matured for 40 years, while the British ruling class blamed all their problems on Brussels, before splattering on the plane of the present in 2016.

So although Macron has been holding a tough line towards Putin’s Russia, there is historic precedent for him to reverse this course. And surely even Macron realizes that being close to China entails proximity to Russia as well. The new BRICS+ paradigm is a Globe of Nations. France will not be in the first rank but perhaps she will find a place in the second echelon?

Exorbitant Dollar Privilege

If de Gaulle correctly read that the globe was in the final chapter of colonization, dollar power was only in its first few. In the years after Bretton Woods, the dollar’s exchange rate was fixed at $35 per ounce of gold. But only governments, who collected too many dollars, were invited to visit the Fed’s gold window for exchange. However, there was a gentlemen’s agreement that since the US was providing military defence for Europe, in return these governments were to understand that gold convertibility was in name only. As the reserve currency, the US had to print enough dollars to facilitate trade. If everyone cashed in their excess dollars for gold, Fort Knox would soon be barren.

De Gaulle guarded France’s sovereignty dearly and he soon understood that dollar hegemony created dependencies that were not compatible with monetary sovereignty. In the mid-Sixties he often attacked the dollar’s exorbitant privilege, a term his finance minister coined, and pushed for an international gold standard regime.

A Time magazine article from 1965 gives an honest and surprisingly informed explanation of the impact an international gold standard would have on the US dollar:

Under a gold standard the U.S. would no longer be able to pay its foreign debts in dollars, but only in gold. U.S. businessmen would have to curtail their investments in foreign companies. (de Gaulle last week called such U.S. investments "a form of expropriation"). Until the U.S. balanced its payments in gold, American consumers would also have to reduce their purchases of foreign goods. Reason: since dollars would no longer be as good as gold, they would be cashed in abroad for gold as soon as spent. The U.S. would immediately become less potent in world economic affairs because, though it has twice the gross national product of the Common Market nations, it holds scarcely more gold than the Six.

Stern Discipline. Conscious no doubt of the irony involved in his unneighborly attack, de Gaulle christened his plan the "Golden Rule." What could be said for his proposal? The value of money would be guaranteed by the immutability of gold. In theory, the world monetary system would become more stable, less vulnerable to crises of confidence. By tying the money supply to gold, the system would prevent overspending. In the U.S. and Britain, which now can pay their deficits out of their own currencies, it would impose a stern fiscal discipline, curb deficit financing and do away with many of the excesses that lead to inflation and recessions. Among other things, it would force the U.S. to eliminate its balance-of-payments deficit quickly, by hook or by crook.

$30 trillion of debt and a massive deindustrialization later these consequences sound like solutions. But once beyond gold’s fetish aura, it is a commodity like any other. It’s value is not determined by some transcendent other-worldly being. Like any other commodity, its price varies according to supply and demand. And so while having some reference to a basket of commodities may provide stability, a simple return to a true gold standard, something Europe had not had for a hundred years, was not a realistic answer.

When Europeans complained about the unfair benefits the US garnered from the dollar, American officials shot back that most of the problems would be solved if Europe would pay for its own defence. In the end, the Europeans refused and Nixon took matters into his own hands when he slammed shut the gold window in 1971.

Since then France has joined the Euro and lost any semblance of monetary sovereignty. Will the BRICS+ partially reopen the gold window later this year when they announce their multilateral reserve currency regime, which may be linked to a basket of commodities, including gold?

Revolt in Paradise: May ‘68 — Colour Revolution avant la lettre.

The May ‘68 student uprisings in France began a chain of events that climaxed in Charles de Gaulle’s resignation in April of 1969. These protests, which were replicated in much of the West, occurred at what in hindsight was the peak post-WW2 golden age of capitalism. Health care and education were free and high quality, jobs were plentiful and secure, and a house and four kids were affordable on a single income. So why were these pampered baby-boomer teenagers protesting? According to French journalist Pierre Viansson-Ponté, “la jeunesse s'ennuie” [the youth are bored]. Over the following decades, these 68-tards got much more excitement than they bargained for as neoliberalism stripped away social protections. As precarity today propels a new generation of youth back onto the streets, Paris could be called many things, but boring is not one of them.

The war in Algeria served as a catalyst for vast changes in France. With the money saved from cutting Algeria loose, De Gaulle achieved a world-class welfare state. Those students in May ‘68 should have been marching in the streets in celebration of the social democracy France was providing.

Likewise the war in Ukraine is a catalyst for tectonic shifts in global power. Can Macron, wearing the mask of de Gaulle, redeem the giant’s dream by leading France towards a multipolar Globe of Nations?

Whether rhyming, echoing or fading to farce, during the past year the metronome of history has been pumping out its pulses at a frenzied tempo. Will events one day confirm de Gaulle’s most grandiose prophesy?

“The facts may prove me wrong,” [de Gaulle] once declared . . . , “but history will prove me right.”