Years of Dread: Part 3 – Strategy of Tension

A case study in how Italy’s Years of Lead used tension to erode national sovereignty in favour of the promised stability of supranational governance.

In Years of Dread: Part 1 – The Gathering Storm, I explored the idea—far from unprecedented—that Ukraine’s eventual defeat, with large portions of its territory falling under Russian control, could trigger twin waves of terrorism in the US and EU. My focus, however, was on their distinct characteristics: one, a sharp and targeted campaign of assassinations; the other, a more diffuse and covert effort to manipulate tensions and justify the expansion of Europe’s military ambitions—two responses born from the same geopolitical wound. Years of Dread: Part 2 – Lost Causes examined how nations process defeat, whether through chaos, resilience, or the thirst for retribution leads to either revenge or revanche. This instalment, Years of Dread: Part 3 – Strategy of Tension turns to Cold War Italy as a case study in how sustained domestic political violence, and the tension it creates, can shape—and ultimately serve—supranational strategic interests.

History turned in 1968—a hinge between two eras. Post-war prosperity, built on economic growth and social compromise, suddenly felt fragile. Across continents, a restless energy erupted, protests and uprisings exposing the tensions slowly accumulating beneath the surface.

The United States in 1968 was a nation convulsing from loss. The assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy sent shockwaves through the country—King’s murder igniting flames in a hundred cities, RFK’s execution stripping the nation of a leader who might have steadied it before it spiralled further into chaos. Months later, the Democratic Convention in Chicago collapsed into violence—tear gas clouding the air, batons swinging, youth clashing with police as the fractures deepened.

From California, came a different kind of darkness. The utopian dream of the counterculture curdled with the rise of the Manson Family, an omen of the state’s future trajectory, where disillusionment and violence would intermix and temper grandiose wealth and utopian idealism.

Europe fared no better. In France, the streets of Paris swelled with striking workers and defiant students, ten million strong by May, as De Gaulle’s hold on power wavered. In Italy, the first spark ignited at Rome University, where the clashes set the stage for the Hot Autumn of 1969, a season of factory strikes and student uprisings that pushed the state to its limits.

Ironically, 1968 was also the high-water mark of Western economic equality. According to economist Thomas Piketty, the bottom 90% of Americans earned approximately 67% of the nation's income at the time, an historic high. In Europe, the wage gap between factory workers and doctors narrowed to historic lows, often 4:1 or less. Unions stood firm, social welfare systems were robust, and the working class enjoyed a standard of living unseen since the dawn of industrialization. Factories still roared, their hulking frames not yet gutted and rusted by decline.

In hindsight, the left should have been conservatives in 1968, not marching in protest but in celebration—commemorating capitalism’s rare bounty of social justice, its brief alignment with prosperity and fairness. As working-class men tinkered with their muscle cars in the driveways of affordable suburban homes, few could have imagined the fate that awaited their class progeny half a century later.

Instead, helter skelter was increasingly the order of the day. With economic justice largely secured, the battleground shifted from class to identity—race, sex, and orientation becoming the new frontiers of struggle. Revolution, not preservation, seized the imagination, and the upheaval that followed would ultimately clear the path for capital to again exasperate the economic inequalities radicals claimed to resist. Today, the bottom 90% earn just half of the nation’s income, with this share steadily shrinking.

The revolts of 1968 were not the cause of the unravelling but a symptom of it—a pivot point marking the last stand of wealth-producing industrialism before the ascent of wealth-extracting financialization. Capital, swollen from decades of steel and assembly lines, began its slow retreat, abandoning tangible production to chase speculative returns. Western prosperity, once built on the dignity of labour, was quietly sacrificed, as factories shuttered and investment flowed eastward in search of cheaper hands.

Across the Pacific, in the future landing site of Western industry, Mao’s Cultural Revolution in 1968 raged at its peak, tearing through China with ideological purges and violent upheavals. What began as a campaign to rekindle revolutionary fervour collapsed into mob rule—students denouncing their teachers, families ripped apart, the old order devoured in a frenzy of forced rebirth.

Like the chaos in the West, China’s upheaval was not the uprising of the oppressed but the convulsions of a system consuming itself. Yet while the West’s unmaking led to long-term decline, China’s brutal reset—defying all contemporary logic—paved the way for its rise. The leaders who endured the Cultural Revolution would later turn to market reforms, unleashing small-scale enterprise and setting China’s production cycle in motion. As Western capital fled its own working class, it found a new host in China, where cheap labour and high returns awaited.

Across the world, the revolts of 1968 were not born of poverty but of restlessness—an instinctive rejection of stillness, of a world that seemed too stable, too complete. The antidote to stasis is tension. And so, history swings between these two poles—forever building, forever dismantling, forever seeking something just out of reach.

Years of Lead

Italy’s Anni di Piombo—the Years of Lead—began in 1968 with a moment of apparent partisan unity. At Rome University, leftist and right-wing working-class militants marched together in protest against the police. Post-war prosperity had not washed over Italy with the same intensity as in the US, and so both factions, ignoring the growing stability their local factories brought their communities, instead saw a corrupt establishment, a state seemingly incapable of delivering justice or revolution, and a world teetering between stagnation and crisis. If these militants had realized what globalization had in store for Italy’s working classes, they might have been a bit less driven to undermine the system.

But this working class unity would not last. As the decade ended, ideological currents pulled them apart. Factions of the left embraced a radical version of violent Marxist-Leninist class struggle, while the neofascist right turned toward ultranationalist dreams of a revived order. The coming storm would pit them against each other—and against the state itself.

Right-versus-left factionalism in Italy ran far deeper than mere ideological disputes—it was rooted in the unresolved resentments of World War II. The divide stretched back to the war’s end, when antifascist partisans, many of them communist, helped bring down Mussolini—the archetypal tyrant—believing themselves on the cusp of a broader socialist victory. Their confidence was bolstered by the Soviet Union’s Red Army sweeping through Eastern Europe, seemingly signalling an inevitable leftist ascendancy across the continent.

But the West had other plans. As Italy’s Communist Party (PCI) gained momentum and appeared poised for victory at the ballot box, the newly-formed CIA, determined to keep the country within the Western fold, intervened. In a covert alliance with the mafia, American operatives worked to tilt the 1948 elections in favour of the center-right, Vatican-backed Christian Democrats.

The result ensured that Italy, with its critical position in the Mediterranean, remained firmly in the Western camp and became a founding member of NATO in 1949—an outcome that would set the stage for decades of political tension and violent struggle, between a weak centrist node of power flanked on the left and right by seething partisans seeking revenge or revanche.

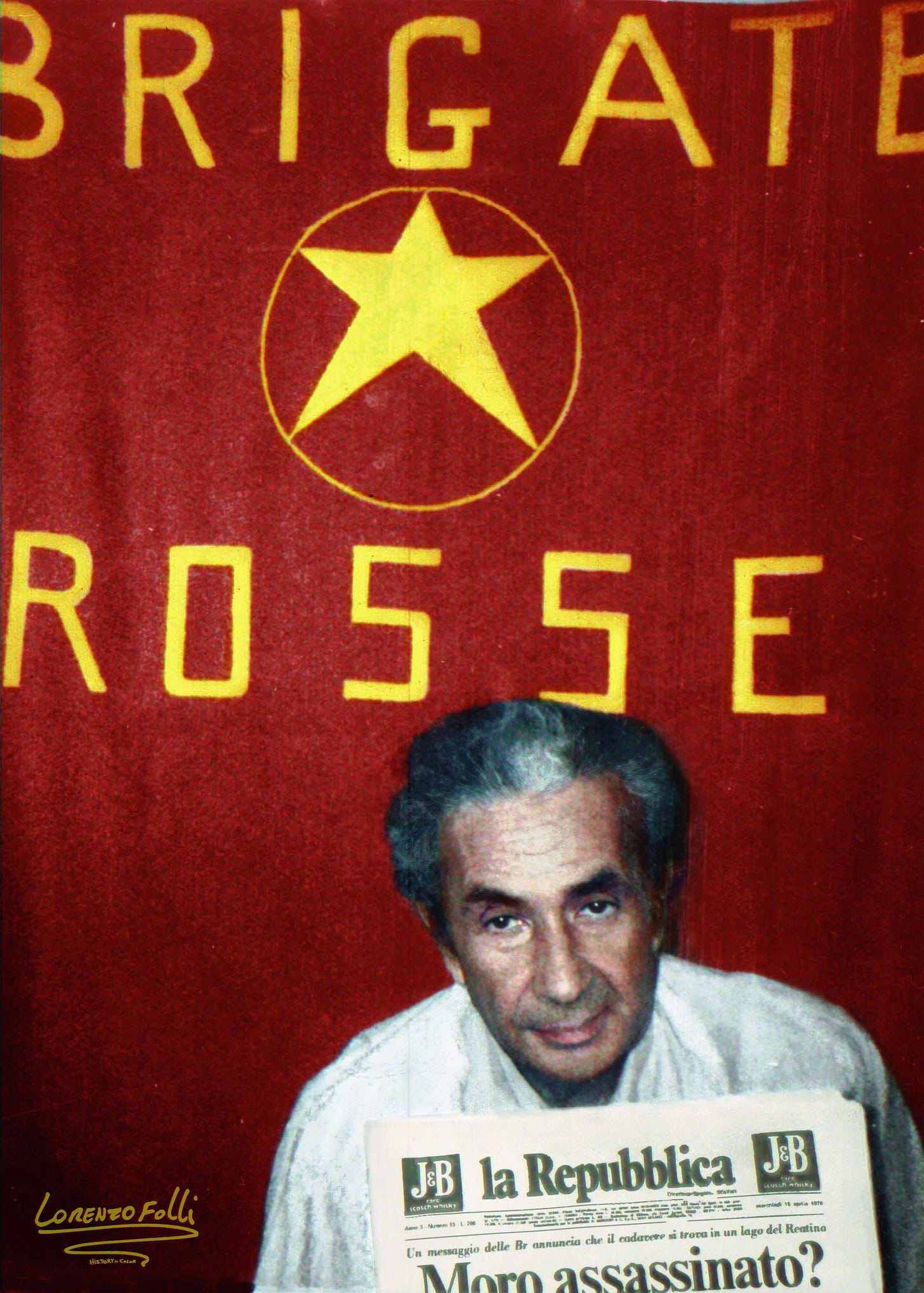

By the early 1970s, it seemed the Italian center could not hold as extremist political violence had spiralled into a parade of terror. The left-wing Red Brigades (Brigate Rosse) emerged as the most infamous militant faction, carrying out targeted assassinations of judges, politicians, industrialists, and military officials—figures they saw as enforcers of capitalist oppression. Their attacks were precise, ideological, and always claimed openly in their own name, making them what could be called “true flag” operations. For the Red Brigades, terror was a means to an end: the destabilization of the Italian state and the rise of a revolutionary proletarian dictatorship.

On the far right, neofascist organizations like New Order (Ordine Nuovo) and National Vanguard (Avanguardia Nazionale) adopted a radically different strategy. Rather than assassinations, they favored indiscriminate bombings in public places—train stations, banks, crowded squares—designed to kill civilians and sow chaos. These attacks were almost always false flag operations, with blame strategically placed on leftist groups to justify state repression.

While waging war against each other in the streets, both the far left and far right pursued the same underlying goal: the Strategy of Tension—a calculated campaign of fear designed to push the public away from moderation and toward authoritarian rule as the only safeguard against chaos. Each faction escalated the violence, believing that heightened tension would force Italy to embrace their vision of order and stasis. The Red Brigades and New Order, despite their ideological divide, both sought to overthrow the system—one through revolution, the other through reaction—using terror as the catalyst for a decisive break from the status quo.

Liddell Hart: The Sledgehammer of Subtlety

Italy’s Years of Lead showcased two opposing approaches to violence: the Red Brigades’ blunt-force terrorism and New Order’s shadowy, calculated misdirection. Together—alongside covert elements within the state—they orchestrated the Strategy of Tension, a campaign of fear that kept Italy in a state of controlled chaos throughout the final decades of the Cold War.

To understand these strategic choices, the military theorist Basil Liddell Hart provides a valuable lens. A veteran of World War I’s senseless carnage, he emerged as one of the 20th century’s foremost strategists, advocating for a more refined, sophisticated way of waging war. In Strategy (1954), he championed the indirect approach—destabilizing the enemy through deception and manoeuvre—in the best case—ensuring victory before battle was ever joined.

Liddell Hart had nothing but contempt for the direct approach, epitomized by the futile trench warfare of World War I, where success was measured in piles of corpses. Instead, he argued for attacking supply lines, morale, and political cohesion—achieving dominance not through brute force but by masking confrontation within clouds of ambiguity.

Ironically, his own rhetorical style was anything but indirect. His writing was clipped, declarative, and insistent—more drill sergeant than shadowy tactician. It was a case of do as I say, not how I write.

His blunt rhetorical style stands in stark contrast to that of Carl von Clausewitz, the Prussian theorist who viewed war as a continuum—ranging from limited engagements to its theoretical extreme: total annihilation. Where Clausewitz was measured and philosophical, Liddell Hart was forceful and dogmatic. Yet paradoxically, it was Liddell Hart who championed finesse over brute force on the battlefield.

This contrast exposes a deeper strategic irony: if every move is predictably indirect, the approach itself becomes direct. True strategy depends on the dynamic interplay between the two—each meaningless without the other. The art of war is not in choosing one over the other, but in knowing when to shift between them.

Direct and Indirect Approaches During Italy’s Years of Lead

The Red Brigades embodied the direct approach, striking individuals under their own banner with open ideological justification. Their 1978 abduction and execution of former Prime Minister Aldo Moro was both a military action and a political statement, aimed at dismantling the Italian state through escalating revolutionary violence. Yet their visibility proved a weakness—every attack invited fierce retaliation.

On the morning of March 16, 1978, Aldo Moro left his home for what would have been an extraordinary parliamentary meeting—one that would finalize his Christian Democratic Party’s coalition with the Italian Communist Party (PCI). It was to be Moro’s defining moment, a bold attempt to stabilize Italy’s fragile democracy by bringing the PCI into the fold of governance—to deflate the Strategy of Tension into a state of stasis. But Moro never arrived.

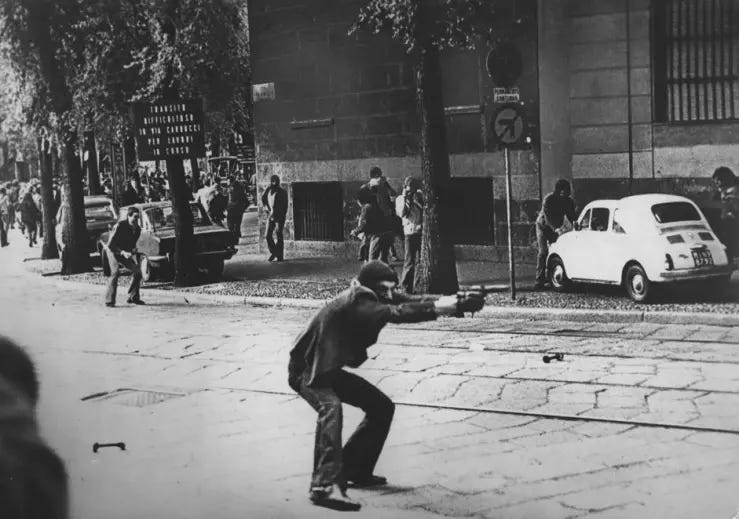

As his convoy passed through Via Fani in Rome, a carefully orchestrated ambush unfolded. A team of Red Brigades militants, disguised as airline pilots, blocked the road and opened fire. In a matter of seconds, Moro’s five bodyguards lay dead, and the former prime minister was dragged from his car and taken to a secret location. For the next 55 days, Italy was held in suspense. The Red Brigades issued communiqués, demanding the release of imprisoned comrades in exchange for Moro’s life. The nation watched, hoping for a resolution.

Yet behind closed doors, Italy’s political establishment had already decided Moro’s fate. The Christian Democrats, the PCI, and the broader state apparatus refused to negotiate, dismissing any attempt at a prisoner exchange. To them, Moro was a tragic but necessary sacrifice—his release, they feared, would legitimize terrorism and embolden further attacks. The US embassy was also loath to see Moro free to consummate his coalition with communism.

On May 9, Moro’s body was found in the trunk of a Renault 4, abandoned on Via Caetani, symbolically positioned between the headquarters of the Christian Democrats and the Communists. His murder marked the definitive collapse of the Historic Compromise. Over the next decade, the PCI lost ground, declining in three consecutive elections before ultimately dissolving in 1989.

Italy’s neofascists, by contrast, perfected the art of the indirect. New Order waged war through deception rather than open battle. Their bombings—most infamously the 1969 Piazza Fontana attack and the 1980 Bologna massacre—were designed to be blamed on leftist extremists, stoking public fear and justifying authoritarian crackdowns.

Amid this climate of deception, suspicions persist about Mario Moretti, the mastermind behind Aldo Moro’s assassination. Some believe he was not a devoted Marxist-Leninist but a neofascist infiltrator, steering the Red Brigades toward actions that ultimately served the interests of the very forces they claimed to oppose.

Despite their ideological opposition, both factions fueled the same cycle of instability. The Red Brigades’ attacks provoked harsh state repression, while neofascist bombings—deliberately misattributed to leftist radicals—deepened public anxiety, justifying authoritarian crackdowns. This was the essence of the Strategy of Tension: a controlled descent into chaos that, rather than toppling the system, ultimately reinforced it—but not in Italy’s favor.

The true victors were neither the radical left nor the far right, but the supranational institutions that emerged stronger in the aftermath. Under the guise of restoring order, NATO and the European project tightened their grip, exchanging Italian sovereignty for the illusion of continental stability. In the end, the Years of Lead did not bring revolution, but the entrenchment of globalist power—ensuring that Italy’s fate would be decided not in Rome, but in Brussels and Washington.

Years of Dread for the US and EU

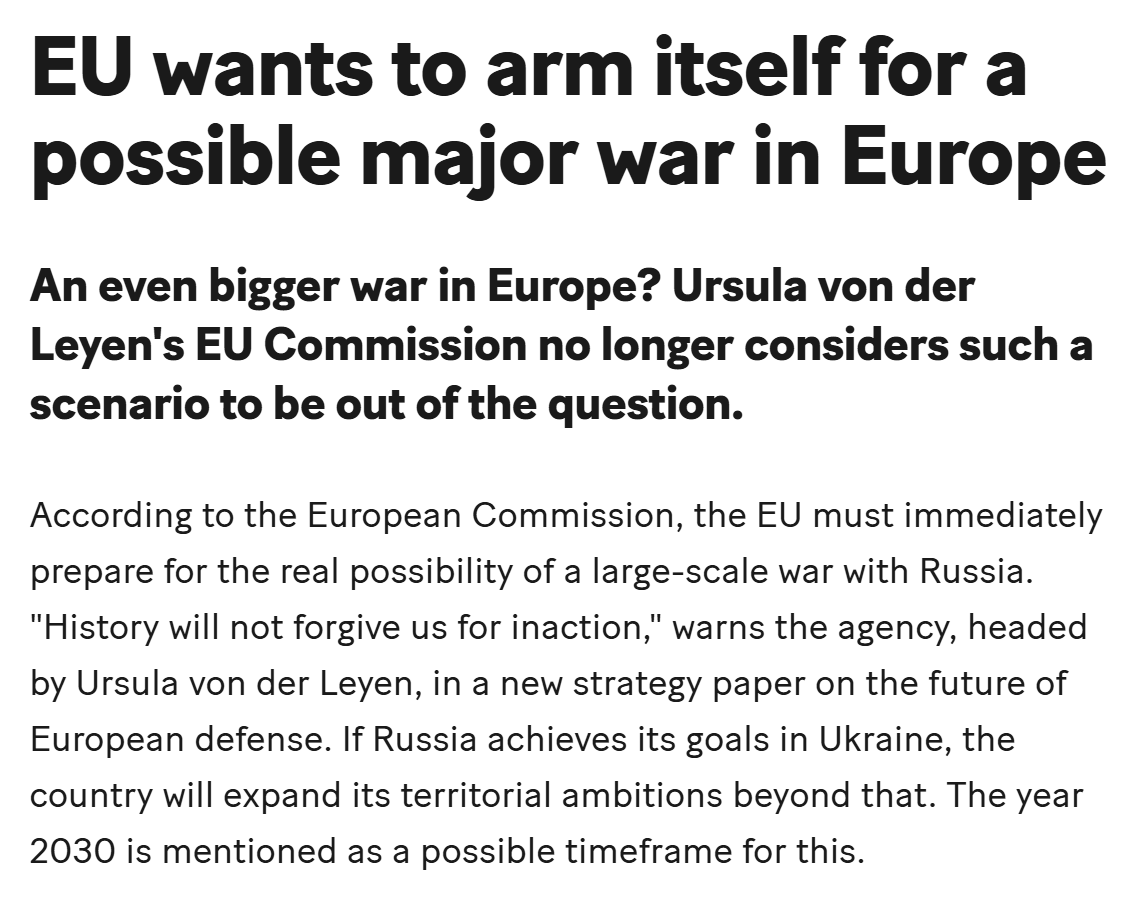

Today, the transfer of state sovereignty from European national capitals to Brussels remains incomplete—largely realized in economic affairs but not in national security. In the wake of Ukraine’s imminent defeat and Europe’s clownishly inept response, the EU has been reduced to little more than a geopolitical spectator. Its only show of strength is the ritualistic group photo—every crisis met with a staged gathering, leaders standing shoulder to shoulder, gazing resolutely into the middle distance.

If no natural catalyst emerges to push European nations toward ceding military and intelligence control to Brussels, an artificial Strategy of Tension may be required—an engineered crisis to jolt Europe from its complacency and force a radical reshaping of the continent’s geopolitical architecture.

Next: Years of Dread: Part 4 – Azov Terror in the US and EU