Years of Dread: Part 2 – Lost Causes

War’s ancient Wheel spins victors and vanquished through time. History shows how the fallen wrestle and win over loss, clawing back to a peak where descent—and woe—wait anew.

In Years of Dread: Part I – The Gathering Storm, I put forward a notion—hardly ground-breaking—that Ukraine’s coming defeat—swathes of its territory falling into Russian hands—will spark twin terrorist waves against the US and EU. My twist lies in describing their differing souls: one, a raw, targeted burst of assassination; the other, a colder, murkier operation, stoking veiled tensions to fuel an EU war machine’s rise—two furies from one wound. Years of Dread: Part II – Lost Causes probes this rift, tracing how defeat bleeds into chaos or clots into resolve, a rhythm pulsing from war’s oldest wounds.

Eternal Churn

War’s Wheel of Fortune spins relentless, grinding civilizations to dust, then lifting fresh powers from the rubble. Every rise masks a fall; every crushed nation yearns to claw back up. Defeat’s no final blow—it’s a gnawing void, from which emerges a drive to reclaim lost pride.

One early tale of this cycle flows from Homer, a Greek poet whose Iliad, set around 1200 BC, charts war’s churn—Greeks snaring victory with the Trojan Horse’s guile. Troy’s collapse hit hard: a fabled city torched, warriors felled, walls broken, its name teetering on oblivion. From Western civilization’s first light, this wheel—war’s ceaseless dance of loss and hunger—shaped its stories, carving defeat’s echo into our oldest songs.

From Troy’s ashes sprang men and myth together—a ragged band of exiles, led by Aeneas, a Trojan prince from Homer’s world, spun their tale from smouldering ruin to forge Rome’s Republic. It conquered, growing into an Empire, its legions ruling the known world. Yet victory stirred the Germanic tribes—barbarians beyond the Rhine, roused by Rome’s gleam, whose raids centuries later shattered its grip, easing Europe into feudal inwardness. Still, war’s Wheel of Fortune spun on. The Renaissance flared in Northern Italy—an empire’s echo in Venice, self-styled as a Most Serene Republic. Its merchant cities wove a web of wealth, planting capitalism’s seeds.

Capitalism’s Venetian dawn marked feudalism’s dusk, sparking bourgeois revolutions—first England, then France—upending old crowns. Yet revolution turns on itself. In France, the 1789 uprising felled a king—Louis XVI’s beheading a monarchy’s bleakest hour—only for the Wheel of Fortune to spin an imperial twist: Napoleon Bonaparte, a Corsican soldier, rose from that republican storm to become Europe’s mightiest emperor. His early conquests stormed Venice in 1797, shattering its serenity under his boots, crushing the once-proud republic’s fading glow.

Napoleon’s rise and fall lay bare history’s turns. In 1806, his victory at Jena—a fierce clash in Prussia’s heart—smashed a kingdom, yet from that shame, Prussia struck a spark of renewal. Georg Hegel, the German philosopher, hailed him as “the world-soul on horseback”—a titan briefly astride Europe. But his 1812 Moscow march, a bold titan’s step, turned tomb—Russia’s winter and scorched earth burying his ambition. War’s Wheel of Fortune dipped, toppling the Corsican who’d soared from France’s revolutionary ash, proving even giants tumble.

Napoleon III’s Farce

Decades after Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1815 fall, his nephew, Napoleon III, grabbed France’s helm, vowing to halt its slide and reclaim faded glory. A brash populist—channelling Donald Trump’s swagger, promising a “great France” without the slogan. In the midst of popular revolutionary chaos, Napoleon III swept the presidency in the 1848 election, launching France’s Second Republic. With charisma and bold moves—reshaping Paris with wide boulevards, flexing military might—he chased a past his France couldn’t hold. His Mexican gambit, propping up Emperor Maximilian, crumbled by 1867, the puppet shot dead. Has Canada skimmed this page of the history book recently?

Yet ambition ran deeper—how could a Napoleon settle for being a mere president? On December 2, 1851, Napoleon III staged a coup, shattering his own Republic and crowning himself Emperor of the Second Empire—a twist spun from his uncle’s shadow. He ruled a France awed by progress—railways, pomp—yet blind to the tide shifting east, where Prussia honed its edge under Otto von Bismarck, a shrewd strategist weaving German unity. The Wheel turned, and France, dazzled, missed the steel rising beyond its borders.

By 1870, that tide broke. Napoleon III’s stand against German unification—fuelled by pride, not power—shattered at Sedan, a brutal north-eastern clash where Prussian cannons pounded his army into dust. Captured and jailed, he fell—a fate today some wish for the “Bad Orange Man.” On January 18, 1871, Prussia’s King Wilhelm I crowned himself German Emperor in Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors, Louis XIV’s opulent relic, with Bismarck smirking nearby. France’s precious Alsace-Lorraine—coal-and-iron borderlands like the Donbass, contested since the 1600s—passed to Germany, a humiliating mark of France’s descent, and Germany’s climb.

Will 2025 replay this story? Ukraine might see its lands—Donbass, perhaps beyond—slide to Russia, a nation broken by defeat in the 1990s after the Cold War’s end, only to rise again under Vladimir Putin’s iron hand. For three decades, Moscow faced Western taunts and NATO’s eastward creep. Putin didn’t lash out in haste; his steel resolve waited, plotting a slow turn of the tide. Today, war’s Wheel of Fortune is hoisting Russia up, its grasp widening as Kiev is trending towards defeat’s bitter void.

Dreamland Cope

German theologian Ernst Troeltsch, following World War I, dubbed defeat’s first phase “Dreamland”—a coping device where nations shed guilt by blaming a father-tyrant: the South’s Confederate leaders post-Civil War, France’s Napoleon III after the Franco-Prussian War, Germany’s Kaiser in 1918. Each saw itself as an innocent mother, duped by bad men, yet dreaming of pre-war purity. The South, beaten in 1865, imagined re-joining the Union as equals, pride intact. France, crushed in 1871, expected to keep Alsace-Lorraine—its precious borderland of fields and iron. Germany, humbled in 1918, clung to restoring its 1914 borders, as if losing a war didn’t have consequences.

Reality shattered Dreamland’s fleeting glow. The South, post-Appomattox in 1865, savoured a brief respite, manufactured a Lost Cause myth, all while expecting equality—then faced Reconstruction’s federal yoke, a rude awakening. France, after 1871’s defeat, nursed a short lull—until the Treaty of Frankfurt stole Alsace-Lorraine away to Germany. Germany, crushed in 1918, clung to a fragile pause—then the Versailles Treaty of 1919 gave Alsace-Lorraine back to France, along with a staggering reparations bill, a bitter loss. Each awoke from denial’s haze to defeat’s jolt, stirring both raw fury and patient grit.

When the guns one day fall silent in Ukraine and Zelensky is ousted, a brief thrill might ripple through—a ceasefire’s fragile glow after years of shells and grief. Ukrainians could drift into their own dreamland: they were faithful proxies in a Great Power chess match, naïve pawns who fought bravely against Russia’s tide. Surely Europe and America, their grandmasters, will shield them—pinning the chaos on Zelensky’s reckless gambits. Surely their guardians will force Moscow back to 2014’s borders with a stern “nyet” to Putin’s land-grasping claws?

But when inevitably Donbass, Crimea, and the other oblasts Russia claims—Ukraine’s eastern and southern lifelines—fall to Moscow, that haze will shatter. After a short lull, fires will flare, one flame rivalling France and Germany’s bloody dance over Alsace-Lorraine, a borderland fuelling decades of war. No peace pact healed that wound; Germany’s total annihilation in 1945 to end that cycle of violence. Ukraine’s coming defeat will not be total, its loss—raw and sprawling—could fester too, poised to unleash a spiral of rage and resolve.

Hot Revenge, Cold Revanche

In Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s The Culture of Defeat (2003), the vanquished don’t fade—their fury spins war’s Wheel of Fortune, a relentless churn where losers and winners swap places. Schivelbusch’s gaze pierces deep: defeat splits into revenge and revanche—twin impulses driving history’s grind.

Revenge burns hot—a raw, untamed cry against the victor’s boot. After the South’s 1865 Appomattox fall, the Ku Klux Klan lashed out, their lynchings a furious rebuke to Reconstruction’s yoke. In France, post-1871, francs-tireurs—rogue sharpshooters—hounded Prussian lines, their guerrilla rage a howl no state could leash. After Germany’s WWI defeat, Freikorps fighters brawled in Weimar’s streets, spitting at betrayal’s bite. Schivelbusch marks this as trauma’s open wound—wild, emotional, a fire beyond control.

Revanche chills colder, a state-forged will to turn loss into redemption. Prussia, crushed by Napoleon in 1806, retooled under Otto von Bismarck, flipping France by 1871 with the Treaty of Frankfurt, seizing Alsace-Lorraine. France’s Third Republic, reeling from Sedan, rebuilt its spine, clawing Alsace-Lorraine back in 1918’s Versailles pact—an archetype of patient resolve. Germany, humbled by that treaty, saw Hitler mould its ashes into 1939’s steel—a slow, collective vow. Schivelbusch notes the fork: revenge flares fast, revanche brews long—both sprout from defeat’s soil, spinning ruin to rise.

Ukraine teeters here now. If Zelensky falls and Russia grabs Donbass-plus, revenge could blaze hot—Azov’s far-right militia, born of 2014’s Maidan, might stalk U.S. and EU nationalists, their molten rage a scream at broken oaths. Revanche, cold and steady, could stir in Brussels—an EU war machine, steely and messianic, swearing to one day wrest Donbass free, mirroring the Third Republic’s reclaiming of lost lands. Defeat’s dance spins anew.

Third Republic and Paris Commune: Revanche Crushes Revenge

Schivelbusch frames the Paris Commune of 1871 not as a pure workers’ uprising—later spun into Marxist lore—but as a blazing mix of populist and nationalist fury, like January 6th’s defiance crossed with Occupy Wall Street’s social vibe. It erupted after France’s 1871 Franco-Prussian defeat, with Alsace-Lorraine lost to Prussia. The fuse lit when the Third Republic—perhaps branded “gun-grabbers” by the defiant—tried to seize Montmartre’s cannons, weapons Parisians had bought to shield their city from invaders who tried to breach their beautiful walls. The Communards weren’t just class rebels; they saw themselves as France’s true patriots, chauvinistically raging at a government they accused of bending the knee to Bismarck.

The Communards, Schivelbusch notes, didn’t aim to shatter France but to topple a regime they felt had “stabbed the nation in the back.” After a few weeks, the Third Republic struck back with semaine sanglante (Bloody Week)—20,000 insurrectionists cut down by a shamed army clawing for honour after Sedan’s rout. This wasn’t mere bourgeois dread; it was revanche’s icy grip, reasserting control. The clash lays bare a timeless rift: the Commune’s fleeting revenge—hot and wild—smashed by the Republic’s patient resolve, a state’s iron over chaos’s fire.

If Ukraine’s ultranationalists, post-defeat, raise rogue flags against a buckling Kiev, we might see it again—raw fury ground down by steely will.

Clytemnestra: The Fire of Revenge

Troy’s fall carves two paths from ruin, first revenge’s blaze, etched in the Oresteia, a trilogy by Aeschylus, a Greek playwright, in 458 BCE. Staged at Athens’ peak—decades before Sparta’s war broke it—the tale burns fierce: a family ripped by blood and betrayal. For those not familiar, Keegan Kjeldsen on The Nietzsche Podcast provides and excellent summary and analysis of this trilogy.

Clytemnestra, echoing the Paris Commune’s hot fury, stands as wife to Agamemnon, a king who led Greeks to raze Troy for Helen, his brother’s stolen queen. Ten years earlier as he departed for war, he sacrificed their daughter Iphigenia to Artemis, goddess of the hunt, for winds—a ruthless crime against bloodkin that ripped Clytemnestra apart. A decade later, when he swaggered back victorious, she lured him to a bath and struck with an axe—no army, just a mother’s rage, wild and unbound.

Her son Orestes, pushed by Apollo, god of prophecy, turned the blade on her—paying fatherblood with motherblood, a son’s revenge as a primal storm, unleashed from Troy’s ashes, defying all taming. Is this hot bloodbath mankind’s tragic forever fate?

Aeneas: The Steel of Revanche

From Troy’s smouldering ashes also rises revanche, cool and steady, in Virgil’s Aeneid, a Roman epic penned in 19 BC. This poetic masterpiece crowns Aeneas, a Trojan prince, as Rome’s mythic founder—dedicated to Augustus, the new emperor who turned Republic to Empire. Virgil wove it as propaganda, casting Augustus as Aeneas’s heir, his rule a fated triumph to heal Rome’s civil wars and anchor its glory. From chaos, it spins order—a patient statecraft lifting defeat to pride. Aeneas flees a city razed by Greeks, his tale a quiet vow to forge anew, echoing the Third Republic: revanche, not revenge, builds from ruin’s sting.

Aeneas fled Troy’s fall around 1200 BC, as Greek invaders set the city ablaze. As flames roared, Hector’s ghost urged him to escape with his father Anchises and Troy’s sacred relics. Jupiter, king of gods, promised an “empire without end.” Aeneas wandered, battled, and settled in Italy, planting Rome’s roots. In the underworld, Anchises foretold Rome’s fate—ruling Greece—and by 146 BCE, Corinth lay in dust. No wild slash for blood, Aeneas’ labour forged a state, raising Troy’s loss to pride.

Athena: Goddess of the New Order

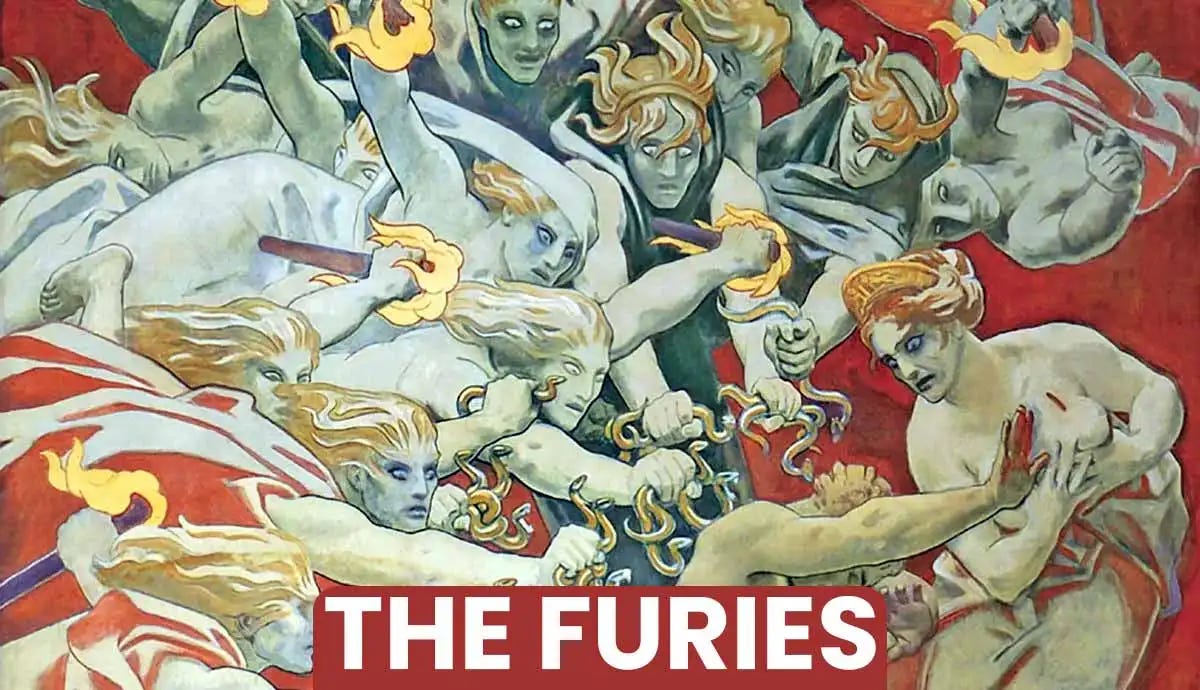

The goddess Athena bridges these worlds, her touch a spark from revenge’s heat to revanche’s steel—a pivot born in Troy’s war, where she herself fanned the flames. Spurned by Paris for Aphrodite’s beauty, she fuelled the Greeks’ wrath, her cunning hand steering their triumph and Troy’s ruin. Now, in the final play of the trilogy, The Eumenides, she turns to quench that fire’s blowback. The Furies—dark goddesses older than Zeus—hunted Orestes for spilling motherblood, their matriarchal bloodlust a primal roar. Winged and fierce, eyes weeping gore, they thrummed with a feminine wrath older than law, craving kinblood’s hot pulse.

Athena strode forth—born from Zeus’s skull, no mothermilk in her, a chiselled figure of cool resolve. She stopped the Furies’ hunt, set Orestes before civilization’s fabled first jury on an Athenian hilltop, her voice steady as iron, weighing his fate, literature’s first courtroom drama.

Apollo, god of prophecy, stood as Orestes’ shield, seeking patriarchal justice—an end to blood’s cursed chain, a father’s death avenged by matricide, cleansed for a new dawn. The jury hung—half demanded vengeance for motherblood spilt, half heeding Apollo’s call for order, a bold plea some hear today to still war’s grind.

Does a modern echo teeter now? Will the slasher of Mother Ukraine slip free, unjudged by an impotent West, blessed by a new patriarch in Washington?

Apollo’s new order prevailed. Athena broke the deadlock, freeing the mother-murderer for a higher call. The Furies wailed—yet with divine force, Athena forged these wild women into Eumenides: “Kindly Ones.” Frenzied hunters of revenge turned into matrons of civic calm. Athena’s steel stills their feral cries—fierce women across seas hushed.

Revenge’s hot flows fade. Order rises yet blood still flows—revanche cold.

Yet beneath Athena’s iron grip, matriarchy’s ancient embers still smoulder, a sultry spark unquenched, new Furies rising to torque war’s Wheel again.

Next: Years of Dread: Part 3—Italy’s Years of Lead