Putin: Between Hitler and Chamberlain

After 20 years of appeasement, Putin finally jettisoned his "peace in our time" policy with the West by invading Ukraine. Can Tucker Carlson pull Putin out of the cold and into alliance with the West?

Some people admire Russian President Vladimir Putin and some do not. A few people manage to study his geopolitical impact with a clear-eyed lack of emotion. What no observer can deny though is that Putin is one of the most poignant and enigmatic statesmen ruling today.

“Are we having a talkshow or a serious conversation,” were the words Putin used to manoeuvre his interview with American journalist Tucker Carlson into a Russian format. His deeply-rooted civilizational view of the world emerged as Putin galivanted across more than a millennium of Russia and Ukraine’s rocky relationship. Despite his unnervingly relaxed tempo, by the end Putin had given an accomplished account of his world-view.

Western societies compress time into an omnipresent “now” where facile thrills and pleasures are consumed. From a short-sighted Western regard, Putin’s discourse seemed rambling and stuck in the past. Tucker tried on several occasions to pull the Russian statesman forward to the frame of the present—but to no avail. Putin insisted on pouring a solid historical foundation before coming up to the clear light of the present era.

Refusing Tucker’s urging to shuck and jive to America’s frenzied tempo of short and shallow outbursts, Putin’s recital emerged as an intriguing adagio—a slow and expressive exposition of Russia’s unique “sonderweg” or special path. From their shared birthplace in Kiev, the trajectories of Russia and Ukraine—at times aligned, other times asunder—intertwined in a double helix of historical tragedy.

Putin intensified his piece with occasional flurries of performative presto, such as sharply hinting that Tucker had a relationship with the CIA. Putin played a sorrowful lament in retelling his friendly advances being scornfully brushed-off by both Presidents Clinton and Bush II. When Tucker called Putin out on his butthurt vibes, Putin went back to playing the cold realist and denied hurt feelings:

Tucker Carlson: Why do you think that is? Just to get to motive. I know, you’re clearly bitter about it. I understand. But why do you think the West rebuffed you then? Why the hostility? Why did the end of the Cold War not fix the relationship? What motivates this from your point of view?

Vladimir Putin: You said I was bitter about the answer. No, it's not bitterness, it's just a statement of fact. We're not the bride and groom, bitterness, resentment, it's not about those kinds of matters in such circumstances. We just realised we weren't welcome there, that's all. Okay, fine.

While Putin’s performance was masterful, it wasn’t pitch perfect. To many ears, a jolt of dissonance sounded when Putin described Poland’s role in the events leading up to the initiation of hostilities in the Second World War.

Independent journalist Michael Tracy is a contrarian who specializes in the destruction of partisan myths and groupthink. Deploying clear evidence of actual events, he both destroys the idealizations partisans project towards their tribe’s beloved leaders and dismantles the devaluations with which they attack adversarial stick figures. An expert on the past decades political events in the US, on military history Tracy has only a limited, normie’s knowledge of WW2. Nevertheless, his non-conformism drives his rejection of simple good guys—bad guys narratives. He can appreciate such shades of grey as Josef Stalin cast as a white hat in the WW2 buddy film—just as easily as the firebombing of Tokyo and Dresden being cast as acts of the righteous. To the general public, such ambiguity never appears as the WW2 myth is rendered in broad and simplistic strokes of good and evil.

Despite his eagerness to seek the grey, Tracy, too, was taken aback by Putin’s diatribe against Polish behaviour in WW2:

There are a several banal explanations for Putin seeming to make a parallel between himself and Hitler. On the surface, since Hitler’s 1941 brutal and unprovoked invasion of the Soviet Union resulted in a bloodbath of 50 million dead Soviet citizens, it is unlikely that Putin even considers the risk that he could ever be seen to be sympathizing with Hitler.

Or, taking the opposite extreme, perhaps Putin has imbibed so much Western propaganda that now, in his own subconscious, he sees himself as Hitler?

A more Machiavellian explanation is that Putin is tempting Poland to defend her past actions. As we will soon see, Poland did in fact collaborate with Hitler and gobbled up a modest portion of Czechoslovakia. Recently, in a strong historical parallel, Putin and other senior Russian spokespeople have been dangling the bait of dividing the former region of Galicia in Western Ukraine between Poland, Hungary and more doubtfully Romania, who all have historic claims/interests in these lands. If Poland defends her past collaboration with Hitler, then that will empower nationalist factions in Poland desiring Lviv. After all, few are going to argue that Putin is worse than Hitler.

Finally, a richer psychological way to look at Putin’s comments is as a tick, a Freudian slip—a symptom—a window deeper into his mind. Often in these cases silence reveals more than words. What should have been said, but wasn’t, is more telling than what was actually heard.

Polish Hyenas

How much historical truth did Putin’s polemic against Poland contain? In the interests of fairness and in the spirit of presenting both sides, let’s first check the British press. With knee-jerk quickness, the much-diminished BBC immediately jumped to Poland’s defence. They ushered in a Polish expert to denounce Putin’s claims. In today’s black and white world of aggressors and victims, and given that Poland clearly was the victim of both Hitler and Stalin’s invasions, the Poles surely must be blameless?

Their expert, Anita Prazmowska, has written several books on the beginning of the Second World War and in them she denounced Polish land-grabbing. But Putin must be proven wrong so the way she denied that Poland had collaborated with Hitler was by deflection. She changed the subject to Poland’s non-aggression treaty with Hitler and then quite reasonably claimed that having a treaty does not rise to the level of collaboration:

Perhaps Mr Putin's most inflammatory claim was regarding Poland. Mr Putin claimed that Poland - which was invaded by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939 - "collaborated with Hitler".

The Russian president told his interviewer that by refusing to cede an area of Poland called the Danzig Corridor to Hitler, Poland "went too far, pushing Hitler to start World War Two by attacking them".

For Prof Prazmowska, President Putin's interpretation of history is a flawed reading of the historical record. She says that while it is true that there were diplomatic contacts between Poland and the Nazis - the first treaty Hitler signed after coming to power was a non-aggression pact with Poland in 1934 - Mr Putin is conflating diplomatic outreach to a threatening neighbour with collaboration.

"The accusation that the Poles were collaborating is nonsense," says Mrs Prazmowska.

"You can't interpret these things as if this were collaboration with Nazi Germany, because it just so happened that the Soviet Union also signed treaties with Germany [at the same time]."

In September 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union invaded Poland according to the terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed between both states earlier that year.

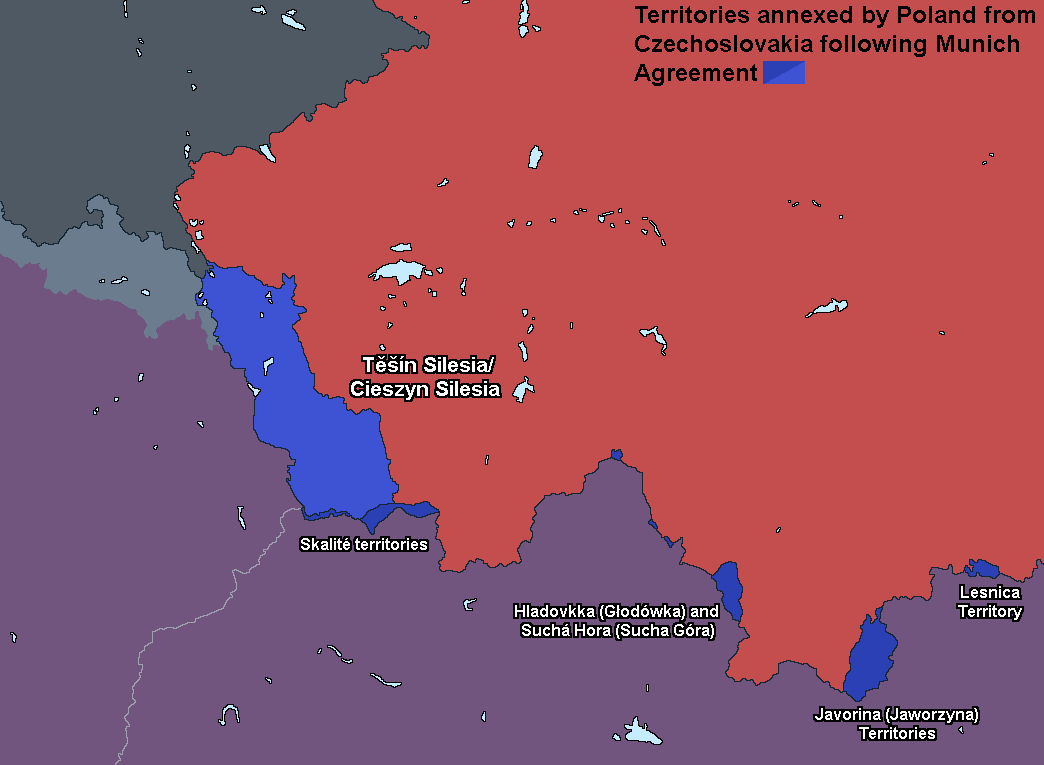

As Professor Prazmowska knows all too well, a quick glance at Wikipedia unambiguously answers the question of whether Poland collaborated with Nazi Germany—beyond just signing a non-aggression pact:

At noon on 30 September [1938], Poland gave an ultimatum to the Czechoslovak government that demanded the immediate evacuation of Czechoslovak troops and police and gave Prague time until noon the following day. At 11:45 a.m. on 1 October the Czechoslovak foreign ministry called the Polish ambassador in Prague and told him that Poland could have what it wanted. The Polish Army, commanded by General Władysław Bortnowski, annexed an area of 801.5 km2 with a population of 227,399 people.

The Germans were delighted with the outcome. They were happy to give up a provincial rail centre to Poland. It was indeed a small sacrifice, spread the blame of the partition of Czechoslovakia, made Poland an accomplice in the process and confused the issue as well as political expectations. Poland was accused of being an accomplice of Nazi Germany.

Winston Churchill was far more scathing in his denunciations of Polish behavior in Czechoslovakia. In The Gathering Storm, the first volume of his history of WW2, Churchill uses his famous rhetorical flair in denouncing the Poles in terms stronger than Putin used:

Poland which with hyena appetite had only six months before joined in the pillage and destruction of the Czechoslovak State.

<…>

The Poles had gained Teschen by their shameful attitude towards the liquidation of the Czechoslovak State. They were soon to pay their own forfeits. (p. 407-9)

Case closed: Poland collaborated with Nazi Germany.

Of course the Soviet Union eventually did as well. They not only grabbed a very large chunk of Poland—which ironically turned out to contain Galicia, home to Ukrainian nationalism and ground zero of the nationalist ideology Russia is today fighting against. Stalin also aided Hitler during his invasion of Norway and benefitted from Hitler’s diplomatic interventions to strong-arm Bessarabia away from Romania. Today Moldova covers much of the area of the former Bessarabia and it too will play a critical role towards the end of the current Ukrainian War.

Did Polish intransigence force Hitler into war?

This is a much richer question and in answering it many parallels with recent geopolitical events come to the fore. Polish pig-headedness certainly played a major role in pushing Hitler towards launching a major European war but was not the determining factor.

To answer this question we rely not only on Winston Churchill, who, while obviously being a stellar statesman, was in fact not the greatest military strategist. He often angered his American allies with his one-track obsession of maintaining Britain’s colonies in the East. For example Churchill was quite sceptical of the Normandy invasion and wanted to instead concentrate on the Mediterranean.

British soldier, military historian and theorist Sir Basil Liddell-Hart was arguably the most outstanding military strategist in the 20th century. After personally suffering the horrors of frontal attacks and meat grinding attrition during the Battle of the Somme, Liddell-Hart, devoted the rest of his life with missionary zeal in promoting an “indirect approach” to warfare. He played a contributing role in the development of Germany’s innovative Blitzkrieg doctrine, however in the post-war era he was often accused of exaggerating his role.

Liddell-Hart’s indirect approach promotes cunning finesse over brute force. He preached surprise, deception, all with the goal of throwing the opponent off balance—both physically and psychologically. He emphasized that war was a domain that required speed, vigour and youth.

Liddell-Hart was a forerunner in theorizing mechanized warfare. Together with J.F.C. Fuller, they promoted:

the transforming power of technology, notably the speed, drama, and novelty of new machines that marked out the twentieth century as distinct from its predecessors. They reflected this wider faith in their constant use of the term “revolution” to denote such a transformation.

John F. Kennedy nicknamed Liddell-Hart, “The Captain who taught Generals” and appropriated his youthful ideas for battle against the stodgy, old Eisenhower Administration.

Liddell-Hart’s mission in life was to avoid another disastrous war like World War 1. His ideas on tank warfare were spurned by the British Army and except for a small faction led by Charles de Gaulle, the ultra conservative French Army also rejected his revolutionary ideas on highly mobile armoured units. The tragedy of history is that the German Army openly embraced Liddell-Hart and Fuller’s ideas and by adding close air support with the use of Stuka dive bombers, created the doctrine of Blitzkrieg.

Liddell-Hart’s History of the Second World War published in 1970, is an excellent source from which to analyse Putin’s Polish polemic. Early on in the book we are met with an unfamiliar view of Hitler:

The last thing that Hitler wanted to produce was another great war. His people, and particularly his generals, were profoundly fearful of any such risk — the experiences of World War I had scarred their minds. To emphasise the basic facts is not to whitewash Hitler’s inherent aggressiveness, nor that of many Germans who eagerly followed his lead. But Hitler, though utterly unscrupulous, was for long cautious in pursuing his aims. The military chiefs were still more cautious and anxious about any step that might provoke a general conflict.

A large part of the German archives were captured after the war, and have thus been available for examination. They reveal an extraordinary degree of trepidation and deep-seated distrust of Germany’s capacity to wage a great war.

Instead of castigating Hitler, Liddell-Hart places much of the blame for the outbreak of WW2 on Britain and France. Britain was at the time in a similar position the United States finds itself today. It was deep into the financialization phase of its cycle of capitalist hegemony. A great maritime power, Britain possessed the most powerful navy known to man at that point. France was a land power and had by far the largest army in the world. The US on the other hand was well into the manufacturing phase of its cycle of capitalist accumulation and was in a very similar position to where China finds herself today—an economic super power but lagging in geopolitical strength. Liddell-Hart continues:

Ever since Hitler’s entry into power, in 1933, the British and French Governments had conceded to this dangerous autocrat immeasurably more than they had been willing to concede to Germany’s previous democratic Governments. At every turn they showed a disposition to avoid trouble and shelve awkward problems — to preserve their present comfort at the expense of the future. (p. 7)

Hitler’s primary strategic goal was to capture more lebensraum—living space—to accommodate the demographic prowess of German wombs. Britain and France were happy to appease Hitler as long as he was moving eastward, towards their bitter enemy the Soviet Union. Liddell-Hart makes clear that Western policy makers were well-informed on Hitler’s plans:

In 1937-8 many of them were frankly realistic in private discussion, though not on public platforms, and many arguments were set forth in British governing circles for allowing Germany to expand eastwards, and thus divert danger from the West. They showed much sympathy with Hitler’s desire for lebensraum — and let him know it. But they shirked thinking out the problem of how the owners could be induced to yield it except to threat of superior force. (p. 8)

Putin claims that after Poland’s rejection of German demands to annex Danzig that Hitler had no choice but to go to war. Liddell-Hart, based on German archives seized at the end of the war, while conceding many of Putin’s points, does not agree that Poland was the ultimate cause of WW2:

At first he {Hitler] did not think of moving against Poland — even though she possessed the largest stretch of territory carved out of Germany after World War I. Poland, like Hungary, had been helpful to him in threatening Czecho-Slovakia’s rear, and thus inducing her to surrender to his demands — Poland, incidentally, had exploited the chance to seize a slice of Czech territory. Hitler was inclined to accept Poland as a junior partner for the time being, on condition that she handed back the German port of Danzig and granted Germany a free route to East Prussia through the Polish ‘Corridor’. On Hitler’s part, it was a remarkably moderate demand in the circumstances. But in successive discussions that winter, Hitler found that the Poles were obstinately disinclined to make any such concession, and also had an inflated idea of their own strength. Even so, he continued to hope that they would come round after further negotiation. As late as March 25 he told his Army Commander-In-Chief that he ‘did not wish to solve the Danzig problem by the use of force’. But a change of mind was produced by an unexpected British step that followed on a fresh step on his part in a different direction. (p. 9-10)

To Liddell-Hart, the ultimate cause of WW2 was the insane decision by Britain to grant a security guarantee to Poland:

The unqualified terms of the guarantee placed Britain’s destiny in the hands of Poland’s rulers, men of very dubious and unstable judgement. Moreover, the guarantee was impossible to fulfil except with Russia’s help, yet no preliminary steps were taken to find out whether Russia would give, or Poland would accept, such aid. (p. 11)

It’s worse than that. The Soviet Union had offered to come to her defence during the Czechoslovakian crisis but Britain declined. The offer was repeated for Poland but this time both Britain and Poland rejected the offer.

Why did Poland’s rulers accept such a fatal offer? Partly because they had an absurdly exaggerated idea of the power of their out of date forces — they boastfully talked of a ‘cavalry ride to Berlin’. Partly because of personal factors: Colonel Beck, shortly afterwards, said that he made up his mind to accept the British offer between ‘two flicks of the ash’ off the cigarette he was smoking. He went on to explain that at his meeting with Hitler in January he had found it hard to swallow Hitler’s remark that Danzig ‘must’ be handed back, and that when the British offer was communicated to him he saw it, and seized it, as a chance to give Hitler a slap in the face. This impulse was only too typical of the ways in which the fate of peoples is often decided.

The only chance of avoiding war now lay in securing the support of Russia — the only power that could give Poland direct support and thus provide a deterrent to Hitler. But, despite the urgency of the situation, the British Government’s steps were dilatory and half-hearted. Chamberlain had a strong dislike of Soviet Russia and Halifax an intense religious antipathy, while both underrated her strength as much as they overrated Poland’s. If they now recognised the desirability of a defensive arrangement with Russia they wanted it on their own terms, and failed to realise that by their precipitate guarantee to Poland they had placed themselves in a position where they would have to sue for it on her terms — as was obvious to Stalin, if not to them. (p. 12)

We must turn to Winston Churchill to fully understand the scale of the blunder Britain made. Chamberlain’s appeasement is well known but what truly caused World War 2 was his wild veering from peace to war.

And now, when every one of these aids and advantages has been squandered and thrown away, Great Britain advances, leading France by the hand, to guarantee the integrity of Poland – of that very Poland which with hyena appetite had only six months before joined in the pillage and destruction of the Czechoslovak State. There was sense in fighting for Czechoslovakia in 1938 when the German Army could scarcely put half a dozen trained divisions on the Western Front, when the French with nearly sixty or seventy divisions could most certainly have rolled forward across the Rhine or into the Ruhr. But this had been judged unreasonable, rash, below the level of modern intellectual thought and morality. Yet now at last the two Western Democracies declared themselves ready to stake their lives upon the territorial integrity of Poland. History, which we are told is mainly the record of the crimes, follies, and miseries of mankind, may be scoured and ransacked to find a parallel to this sudden and complete reversal of five or six years’ policy of easy-going placatory appeasement, and its transformation almost overnight into a readiness to accept an obviously imminent war on far worse conditions and on the greatest scale.

Moreover, how could we protect Poland and make good our guarantee? Only by declaring war upon Germany and attacking a stronger Western Wall and a more powerful German Army than those from which we had recoiled in September, 1938. Here is a line of milestones to disaster. Here is a catalogue of surrenders, at first when all was easy and later when things were harder, to the ever-growing German power. But now at last was the end of British and French submission. Here was decision at last, taken at the worst possible moment and on the least satisfactory ground, which must surely lead to the slaughter of tens of millions of people. Here was the righteous cause deliberately and with a refinement of inverted artistry committed to mortal battle after its assets and advantages had been so improvidently squandered. Still, if you will not fight for the right when you can easily win without bloodshed; if you will not fight when your victory will be sure and not too costly; you may come to the moment when you will have to fight with all the odds against you and only a precarious chance of survival. There may even be a worse case. You may have to fight when there is no hope of victory, because it is better to perish than live as slaves. (p. 407-8)

The reality is the only reason Britain did not surrender was the hope the US would one day come to her aid. Just as Hitler foolishly invaded the Soviet Union, he just as recklessly declared war on America.

Putin as Chamberlain?

In recent days, President Putin has stated that, “the only thing we can regret is that Russia did not begin active operations in Ukraine earlier.” There is no question that if Putin had moved boldly in 2014 he would have easily solved the “Ukrainian Question” in a decisive manner. Instead he waited until 2022, and the price will be much higher.

So instead of the tired old Hitler analogy, a more fruitful comparison, and perhaps explanation for Putin’s strange comments on Poland, would be to see Putin as this generation’s Neville Chamberlain.

For the past year Putin has been giving “butthurt” speeches about how he miscalculated the West and rejected all his attempts at peace and partnership. Putin did indeed beg the West to accept Russia as the their geopolitical side chick but got spurned. Is Putin really so versed in history and yet remains unaware of the previous 200 years of outright Western hostility towards Russia? Is he not aware of the infamous “Testament of Peter the Great” a forgery that promotes a Russian conspiracy to conquer the globe that is eerily similar to "The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion,” a fabricated text that illustrates a plot for Jewish world domination?

There are strong parallels between the German humiliation after World War 1 and the Russian downfall following her defeat in the Cold War. Both suffered from a decade of economic and cultural depravity, which featured periods of hyperinflation. Both were coming off authoritarian glory days but struggled with their first experience of democracy. In Germany the Versailles treaty was imposed to punish Germany. In Russia, the US-led Harvard Gang of neoliberal economists imposed a punitive shock therapy which immiserated the common people and enriched a rising, pro-Western oligarch class.

The failures of the Weimar Republic brought Hitler to power. In a similar way, the catastrophe of the Yeltsin years was finally ended by a soft coup provoked by Yeltsin’s appeasement towards the West, resulting in NATO’s bombing and dismemberment campaign on Russia’s long-time ally Serbia.

Putin moved ruthlessly on Yeltsin-era oligarchs, replacing them with a group of his own men, but in doing so earned a deeper hatred from the West. Nevertheless, Putin continued Yeltsin’s policy of appeasement towards the West. Despite his recent rejection by President Clinton, immediately after 9/11, Putin was the first foreign leader to contact Bush II and opened Central Asian bases for American use. To thank Putin for his kind gesture, Bush II unilaterally pulled out of the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty which opened the way for the US to install ballistic missiles in Romania. The official justification was to defend against an Iranian missile attack but the installations can just as easily launch offensive missiles towards Moscow.

In the meantime NATO was expanding eastward. Yes, Western leaders had promised “not an inch eastward” but Putin understands geopolitics well enough to know Thucydides’ Melian Dialogue, “right, as the world goes, is only in question between equal power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” Russian weakness created a vacuum in Eastern Europe and naturally NATO rushed in to fill the power-void.

Back in 1939, Neville Chamberlain’s error was in flipping from one radically misguided policy of appeasement to an equally deluded policy of triggering a war he had no means to execute. Did Putin catch a clue after the ABM fiasco? No. The US went on to launch a coup d’etat in Ukraine, the so-called Orange Revolution. All the while, the US was funnelling money and Jihadis into Chechnya. In response to these Western provocations, Russia doubled-down on appeasement by voting for UN sanctions against North Korea in 2006.

Russia has always been split between reformers who look Westward and traditionalists who embrace her Eurasian roots. Putin, who served as a KGB officer in Dresden Germany, is fluent in German and speaks English well. He is from St. Petersburg, the capital of Russian pro-Western liberalism.

Finally in 2007 at the Munich Security Conference, Putin started to tack away from the West. His speech denounced America’s unipolar world. In contrast to Chamberlain, Putin did not exaggerate his transformation. A more cynical view is that his Munich speech bought him some time and space from the Kremlin hawks to continue his appeasement policies.

In 2008, NATO proclaimed their intention to expand into Ukraine and Georgia. In the same year Putin launched a limited invasion of Georgia, capturing a portion along the Black Sea coast.

In 2014, the US manufactured a coup d'état in Ukraine. in response the Donbass region erupted in violent opposition. With Russia’s vital Black Sea port of Sebastopol under threat of NATO occupation, Putin made a reluctant and minimalist move of capturing the Crimean peninsula. Even in this operation Putin meekly used “Little Green Men” to hide Russian complicity.

In hindsight Putin made a critical error in 2014. Instead of launching an outright invasion of Ukraine, which would have literally been a cakewalk. In one grand stroke he could have answered the Ukrainian Question for good. Yes he might have struggled with some sanctions. But instead he dithered and negotiated with the French and Germans, agreeing to the monstrosity of Minsk II and abandoning residents of the Donbass to nearly a decade of indiscriminate Ukrainian shelling.

This failure corresponds to Churchill’s “if you will not fight when your victory will be sure and not too costly”

And yet in 2018, Putin made another egregious error in agreeing to invest in the Nord Stream 2 pipeline to Germany. As Putin was forced to admit to Tucker, the CIA blew up Nord Stream 2 and with it Russia’s investment of nearly €5 billion.

Putin: From Failure to Success

During the run-up to WW2, in echoes of Putin’s failed attempts to couple with the West, Stalin offered twice to form an alliance during the Czechoslovakian and Polish crises. He was rejected both times and instead reluctantly accepted Hitler’s advances. Indeed in 1939, Germany, USSR, Italy and Japan formed a formidable alliance on paper and should have been able to obtain hegemony over the world-island of Eurasia during Global War 5. Hitler destroyed this possibility with his foolish invasion of the USSR, leading to a victory for the United States with a global runner-up position for the USSR.

Only in February of 2022 did Putin finally do a full-Chamberlain by unambiguously ditching the West and—eight years too late—launched an invasion of Ukraine. While Russia is still very likely to emerge victorious, before it is over, it may come at the price of one million Slavic casualties instead of the roughly ten thousand that would have perished in 2014.

In the larger global picture though, things are brighter. During these early days of Global War 6, Russia finds herself aligned with China, Iran, North Korea, along with much of the Global South, as well as being embedded in the BRICS-10 trade grouping. Just as Stalin never imagined he would one day be in cahoots with Nazi Germany, the current global alliance structure is not the way a young Putin, fawning over Tony Blair, saw Russia’s future.

In the runup to WW2, the US was the heir apparent to the capitalist productive machine. Today this role is held by China. For all the talk of China’s economic problems, they pale in comparison to the depression the US suffered in the 30’s.

Currently the Global War 6 alignments are as follows:

For the Globalist West:

Today’s USA equals WW2’s Britain and France.

Today’s EU equals WW2’s Italy.

Today’s South Korea and Japan equal WW2’s Australia and New Zealand.

For the Realist Eurasians:

Today’s China equals WW2’s USA.

Today’s Russia equals WW2’s USSR.

Today’s Iran equals WW2’s Japan.

Today’s North Korea equals WW2’s China.

Despite his years of appeasement, Putin has now landed on his feet and is a key member of the stronger alliance. Putin to his credit did not react hysterically to his multiple public humiliations at the hands of the West. This is in stark contrast to how Neville Chamberlain handled Hitler’s humiliations, as Liddell-Hart emphasizes:

Within a few days, however, Chamberlain made a complete ‘about-turn’ — so sudden and far-reaching that it amazed the world. He jumped to a decision to block any following move of Hitler’s <…>

It is impossible to gauge what was the predominant influence on his impulse — the pressure of public indignation, or his own indignation, or his anger at having been fooled by Hitler, or his humiliation at having been made to look a fool in the eyes of his own people. (p.11)

Instead of attempting to execute a Neville Chamberlain-style instantaneous geopolitical U-turn, Putin has gently tacked from appeasement to aggression over nearly15 years of hesitant shifts.

Russia’s Eurasian Future

During Putin’s reign, a strong Eurasian faction, headed by intellectual Aleksandr Dugin, operated as a loyal opposition to challenge the pro-Western Putin faction. Dugin represents tradition, religion, respect for antiquity and embraces classical philosophy. To Dugin, the West stands for materialism, atheism, secularisation, humanism and ultimately nihilism. He insists the culminating point of the West’s unipolar expansion was the rising of the Donbass against the 2014 globalist coup d'état in Kiev.

Today traditionalists across the globe look to Putin for leadership. Tucker Carlson feigns respect for Putin. Tucker’s father Dick Carlson almost certainly worked for US intelligence and it is likely that Tucker does as well—Putin certainly hinted so. Tucker’s interview can be seen as an initial US attempt to peel Russia away from its alliance with China. For Global War 6, if the US is to emerge victorious, it must by all means change the current global line-up. Just as Churchill rued Chamberlain’s hasty dismissals of Stalin’s offers of alliance, he couldn’t believe his great fortune the day Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa and threw the power of Russia into the Ally’s laps.

Currently the schizophrenic American political alignment has the Republicans leaning pro-Russian, moderately anti-Chinese and rabidly anti-Iranian. The Democrats are the mirror image, leaning pro-Iranian, moderately anti-Chinese, and rabidly anti-Russian.

And so one way to decipher Putin’s “Danzig tick” is that he was placing himself in the appeasing shoes of Neville Chamberlain and not Hitler’s. His historical analogy as to why Poland couldn’t accept Hitler’s terms were from a place of an appeaser’s regret. Why couldn’t the Ukrainians simply accept the reasonable deal contained in Minsk 2? That way Putin’s twenty years of appeasement might have born fruit, or at least gotten him into retirement. During his discussion of Poland, Putin was silent on the wild swings between appeasement and impotent warmongering that characterize Chamberlain’s culpability.

The question remains of whether Hitler really would have stopped his expansionist ways after Danzig? And in a similar manner, would the West’s more than two centuries of jihad against Russia have really stopped at Minsk 2? It is true that during both Global War 4 and 5—the Napoleonic Wars and WW1-2—there were indeed temporary truces between the West and Russia. Both times this worked to the great benefit of the West, with Russia taking the brunt of an invasion first by Napoleon and then by Hitler. Will Tucker’s tentative offer of détente with Putin lead Russia to dump its current alliance to come running back to the West—this time for Global War 6?

No.