Oriental Despotism: History's Eternally Circular Return

The rise of the multipolar order led by strong centralized states threatens to jettison Liberal Democracy into the dustbin of history along with the idea of a linear progression of history.

In Fredrich Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil, the 19th century German philosopher wryly observes:

It is certainly not the least charm of a theory that it is refutable; it is precisely thereby that it attracts the more subtle minds. It seems that the hundred-times-refuted theory of the “free will” owes its persistence to this charm alone; someone is always appearing who feels himself strong enough to refute it.

A recent example of a theory so charming that it has suffered hundreds of refutations is Francis Fukuyama’s theory of permanent US global dominance proffered in his popular 1989 article, The End of History? Fukuyama prophesized that as the Cold War waned, and with the apparent collapse of the Marxist-Leninist orthodoxies in China and Russia, there were no more “grand ideas” to challenge Western liberal democracy:

The triumph of the West, of the Western idea, is evident first of all in the total exhaustion of viable systematic alternatives to Western liberalism. In the past decade, there have been unmistakable changes in the intellectual climate of the world's two largest communist countries, and the beginnings of significant reform movements in both. But this phenomenon extends beyond high politics and it can be seen also in the ineluctable spread of consumerist Western culture in such diverse contexts as the peasants' markets and color television sets now omnipresent throughout China, the cooperative restaurants and clothing stores opened in the past year in Moscow, the Beethoven piped into Japanese department stores, and the rock music enjoyed alike in Prague, Rangoon, and Tehran.

What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government. This is not to say that there will no longer be events to fill the pages of Foreign Affair's yearly summaries of international relations, for the victory of liberalism has occurred primarily in the realm of ideas or consciousness and is as yet incomplete in. the real or material world. But there are powerful reasons for believing that it is the ideal that will govern the material world in the long run.

Fukuyama’s long run hit a trenched line of defence in 2022, the year Russia invaded Ukraine. Western sanctions have not only failed to contain Russian ambitions, but have rallied many nations—China, India, and Iran among them—into seeking shelter from Western punitive tyranny. These moves accelerated the previously slow accumulation of global power by Eastern powers. One key node of resistance is the BRICS organization, a trade association looking to counter the despotism of Western sanctions.

Recently the 15th BRICS Summit in Johannesburg, South Africa ended with the multipolar trading organization’s original nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) extending invitations to six new members: Iran, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt, Ethiopia, and Argentina. This new BRICS-11 is intent on challenging US unipolar global power. There are three threads that loosely link the eleven: ancient civilizations, natural resources, and proximity to crucial sea-power choke points.

But in the arena of ideas, at least in Western narratives, the world has now broken down into a battle of authoritarianism versus democracy. The spectre of authoritarianism haunts the West so strongly that dynamic Western political figures and parties, deemed non-democratic by despotic elites, are indicted or banned from political activity. If democracy actually functioned, the people themselves would serve as a sort of immune system against authoritarianism. The absurdity of elites trying to forcefully vaccinate their people against authoritarianism begs the question of who the authoritarians really are?

Oriental Despotism

The term Oriental despotism has fallen out of use but its underlying concept of authoritarian governance is more meaningful than ever. The term Orient is discouraged in some English speaking nations, but it simply signifies the direction of the sunrise. Within the ideological confines of Marxism the concept is known as the Asiatic Mode of Production (AMP) and is highly controversial among Marxist scholars.

Oriental despotism rose with the dawn of hydraulic civilization in Babylonia, Egypt and in Asia in general. It refers to powerful elites who controlled massive irrigation systems to bring water to arid or semi-arid regions. Great civilizations developed thanks to complex irrigation systems that through a network of dams, dykes, canals and ditches, provided water to arid land and protected crops from periodic flooding. Such societies were by definition despotic since individual freedom was a luxury such economies could not afford. Forced collective labour was the rule in hydraulic farming, where massive collective waterworks were required for survival. Monumental architecture also thrived in such societies where in good times the mass labour was diverted towards ceremonial purposes. Despotic elites would serve planning, managerial and disciplinary functions: peasants donated months of raw labour on demand.

Such organization structures were rare in Western Europe where individualistic rain-water irrigation systems allowed farmers much more autonomy. Where supplies of rain-water are reliable, most of a farmer’s labour is spent on his individual lands and collective forced labour is rare.

A dichotomy between Western individualism and Eastern collectivist power was first conceptualized in ancient Greece and was used as a key ideological distinction between the Greek nations of free peoples and the barbarian Persian Empire. While the Greeks may at times fall under the power of a tyrant, this type of government is illegitimate because Greeks were thought to be born free and should have a substantial stake in governing themselves. Orientals were believed to be born slaves to their Emperor and so the despotism of the Eastern authoritarians is considered legitimate:

In many respects, this was a crucial distinction which enabled the Greeks to theoretically justify their future attitudes towards Asiatic societies and political systems. First, Aristotle's theory clearly qualified despotism as incompatible with the natural character of the Greek people, who were free and could only temporarily be subject to tyranny because they would revolt against it as soon as possible. Instead, despotism was said to be the most suitable form of government for barbarous nations, mainly the Persians, who were thought to have a natural tendency towards subordination and would thus accept authorities which would be intolerable for the Greeks without opposition or apparent pain. Despotism, for Aristotle, was therefore not degeneration, but a proper and possibly durable system in radical opposition to the Greek world and mind. This judgment followed from the idea that different ethnic groups were naturally compatible with different systems of government, which is an important element of Aristotle's political thought.

When Alexander the Great invaded the Orient, a powerful cleavage was cut between his political personage and his soldiers. As his victories stacked higher, Alexander increasingly took on the appearance of a God-like Emperor. Alexander defended against any accusations of “going native” by emphasizing that he was obligated to assume a despotic role to convince his newly conquered Oriental subjects to obey him. We still see this ambivalence today. The West is fervently proud of its liberal democratic societies and yet attempts to rule the world as an absolutist authoritarian despot. International (Western) despotism is thus manifest towards outsiders, either directly in the past through European colonialism or indirectly today with US-led globalization. A variant of Oriental despotism was recently articulated in EU diplomat Josep Borrell’s analogy of the West being a “garden” and most of the rest of the world being a “jungle.”

However, there are indeed cultural differences between the West and the nation-states ruling areas where the great irrigation civilizations of the past: China, Egypt, Russia, India, Iran, Arabia, Ethiopia, etc, once thrived. These nations tend to promote the collective and may appear more authoritarian and centralized than the West. But in sharp contrast to their domestic systems, these up-and-coming nation’s conception of international relations is much more liberal and democratic. This is highlighted in the non-hegemonic features of the collaborative and multipolar BRICS-11 order.

The ancient Greek division of the world is still salient as Western liberal democracy battles Eastern authoritarianism on the pages of Western media.

Hegel’s End of History

Fukuyama based his theory of Western triumph on German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s concept of the end of history. Hegel’s mission was no less than to discern the ultimate purpose of mankind by revealing the inner kernel of human potentiality. The law of history according to Hegel is the incremental increase in Freedom and Rationality. Over time, as humans begin to understand their ultimate purpose—what the “ends” of history are—our societies will more easily climb the progressive ladder of history. For Hegel, the end of history is absolute knowledge of the world brought about by a benevolent state:

What distinguished Hegel's approach is that he placed despotism within a dialectical scheme which is chronological and logical at the same time, since it is the first phase of the historical and universal movement of the spirit. Despotism, which for Hegel was represented by Asiatic societies and governments, was conceived of as the first of four stages in the dialectics of the universal spirit, because it departs from the state of nature but does not yet permit the individual to be autonomous. A despotically ruled society cannot articulate itself, and the universal spirit is concentrated in a single free person, embodied by the despot himself. The logical analysis of the spirit's development implies an historical movement, and in Hegel's view "the History of the World travels from East to West, for Europe is absolutely the end of History."

<…>

Geographical factors interact with the logical development of the spirit, which Hegel divided into four great stages, that is, the Oriental, Greek, Roman and, finally, Germanic stage. The particular history of each people's spirit is also influenced by geographic factors such as the different lifestyles in the uplands or in the plains of the Eastern world. The Eastern world represents the first stage of the universal spirit's movement – "the childhood of History" – since it remains locked in a condition which, by restricting the role of the individual, does not permit any evolution.

One potential flaw in Hegel’s thinking is seeing the nation-state as the final structure of human development. There is an obvious progression towards larger political units and so why not conceive the global political structure as the direction history is trending? If so, the capitalist era of global hegemons, of which we are in the last stages of the American version, serves as a sort of International despotism. Only nation-states steeled by a powerful governments that demand freedom from US authoritarian global power will be able to move the international global order from a unipolar Oriental model towards the next stage, if we accept Hegel’s progression, a Greek model of multipolar nation-states.

For Hegel, Oriental despotism was a manifestation of stagnant land power. The Phoenician innovation of maritime power, with international trade and settler colonies, was what marked the transition from the Oriental to the Greek world.

The extraordinary theoretical strength of Hegel's thought reinforced the idea of an inexorable connection between despotism and immobility and an essential difference between the Eastern and the European world which had already been discussed in the Age of Enlightenment. Its influence, from a theoretical but also from a political and ideological point of view, was considerable. If Asia was located at the origin of the universal spirit's movement, its lack of dynamics placed it outside the development of civilization.

BRICS-11 Expansion: Controlling Naval Choke Points

One manifestation of the rising multipolar order’s desire to push beyond the limits of International despotism and to create a new global architecture is their increasing interest in naval power. For example one theme in the recent BRICS-11 expansion was a desire to grab control of global naval choke points. Choke points are geographical features that funnel human activity into a narrow band. The Panama Canal and Suez Canal are manmade naval choke points, created to avoid other choke points and to shorten the length of shipping routes. The Panama Canal allowed shipping to pass from the Pacific to Atlantic ocean while avoiding circumnavigating South America. The Suez Canal allowed similar passage from the Mediterranean to the Indian ocean by avoiding a long detour around Africa. As the globe bifurcates into two blocs pitting the American-led G7 against the Chinese-led BRICS11, control of these choke points will be crucial when Global War 6 ignites into all-out war.

The addition of Iran, Saudi Arabia and UAE gives the BRICS-11 a power position in the Persian Gulf and in particular the critical Straights of Hormuz. Egypt provides the BRICS with control over the Suez Canal and a powerful position on the Red Sea, with Saudi Arabia on the opposite shore. China’s existing naval base in Djibouti gives the BRICS control over the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait entrance to the Red Sea.

If Argentina joins the BRICS then the multipolar alliance will have a strong position close to the Strait of Magellan is at southern tip of Argentina and Chile. This southern oceanic passage lost importance with the opening of the Panama Canal but in the event of a global war—assuming the US would shut down the Panama Canal to Chinese shipping—it would serve as a crucial route to supply Brazilian and Argentinian agricultural products to China. In addition, large US aircraft carriers, which are too wide for the Panama Canal, must pass through this narrow strait. Eventually adding Chile to the BRICS-11 line-up would further secure this sea route since they officially control the Strait.

Oriental Despotic Capitalism

China hydraulic agricultural economy was led by a powerful emperor — today China’s electric vehicle industry is led in a similar fashion. For decades the Chinese government has subsidized battery makers and has helped industry dominate the complicated supply chains, including over critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel and manganese. From the Financial Times:

The complaint that China’s success is down to a multi-decade government-planned effort is both true and slightly academic at this stage. The country’s accumulated advantages are daunting. It controls two-thirds of global capacity for processing lithium, the raw material for batteries, and dominates every aspect of battery production. It produced 10 times as many battery vehicles last year as Germany. It has a manufacturing cost advantage of perhaps 20 to 25 per cent. Shipping costs (as well as 10 per cent tariffs) have narrowed that gap but will become less important as China’s exports rise, particularly of the affordable mass-market vehicles that face little European competition.

Erecting trade barriers is a terrible option for an industry reliant on selling to China, and for policymakers wary of the costs of energy transition for consumers. The European industry body this month called for a “robust industrial strategy that guarantees a level playing field” with both China and the US. It is true that UK and European policy — either through complacency or ineptitude — has been heavy on setting targets, like the 2035 halt to sales of combustion engines, and light on planning and support to get there.

Meanwhile the liberal democracies in the West refuse to implement industrial policies and as a result are slowly losing the capitalist struggle. In the West, government intervention is conceived of like in rain-water agricultural societies: the farms/business are autonomous but taxes are collected. In China, the Oriental despotism practises of management, planning and discipline are still practised on industry, just as they were centuries ago on rice farmers.

History’s Merry-go-round

The concept of Oriental despotism was not universally accepted. Adam Smith for example raved about the Chinese economy and saw it as a powerful example for Europe to emulate. Lawrence Krader, in his work The Asiatic Mode of Production, comments on the cynical political motives of pushing the Oriental despotism narrative:

The speculations about the Oriental despotism or tyranny, the forms of landownership in Asia, the Oriental society, supported at one time the mercantilist policies, the advocates of free trade, the East India Company, at another the utili¬ tarians, the liberal interests, and the colonialists throughout.

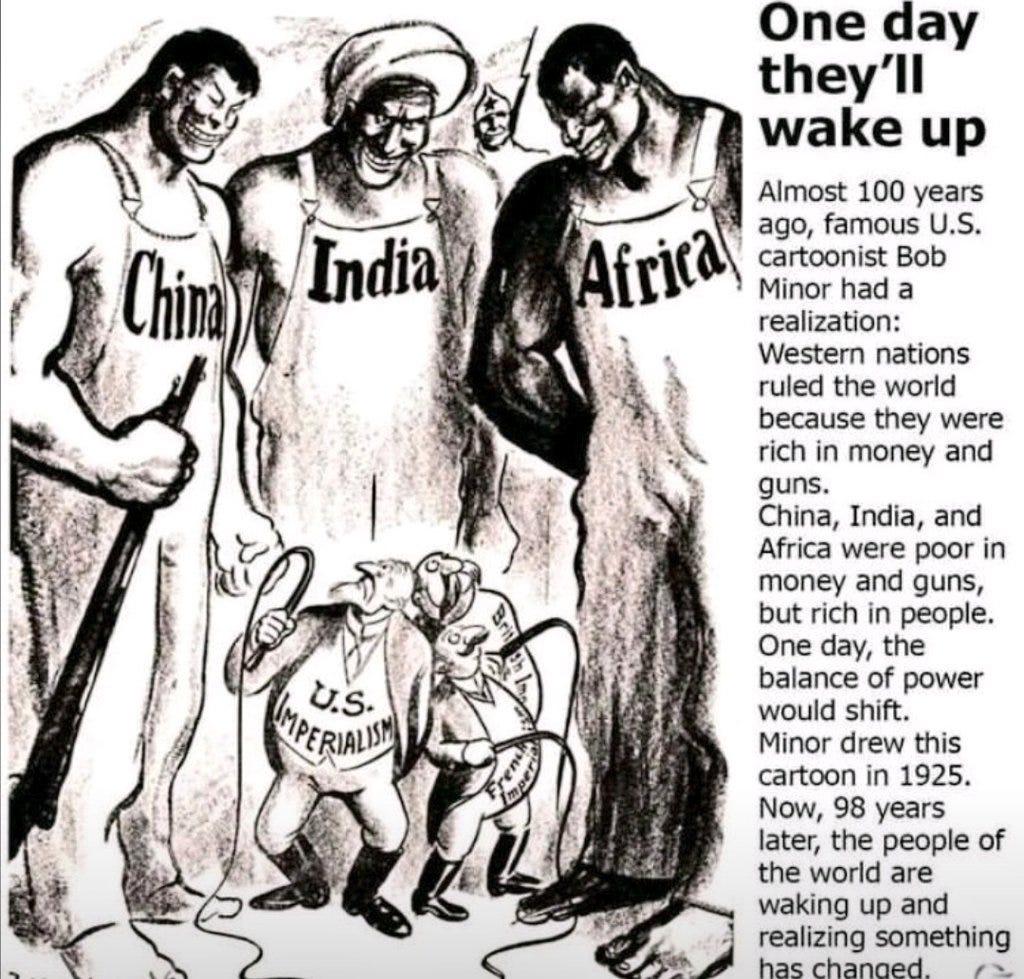

Modern day liberal interventionists are still using a sanitized version of the Oriental despotism narrative to promote US global hegemony. No doubt they are in part driven by the fear illustrated in Bob Minor’s political cartoon above. By the second half of the 20th century, the West’s relative decline became apparent and a future of waning liberal democracy loomed:

"When the twentieth century opened," wrote Geoffrey Barraclough in the mid 1960s, "European power in Asia and Africa stood at its zenith; no nation, it seemed, could withstand the superiority of European arms and commerce. Sixty years later only the vestiges of European domination remained . . . . Never before in the whole of human history had so revolutionary a reversal occurred with such rapidity. " The change in the position of the peoples of Asia and Africa "was the surest sign of the advent of a new era. " Barraclough had few doubts that when the history of the first half of the twentieth century-which for most historians was still dominated by European wars and problems-came to be written in a longer perspective, "no single theme will prove to be of greater importance than the revolt against the west."

The first half of the 21st century has only seen this revolt deepen. As the BRICS-11 add members, as the West’s inability to produce ammunition in quantities required to fuel proxy wars worsens, as the Primal Horde of rising nations starts stretching the capacities of the Western powers on both the economic and military fronts, the second half of our current century may indeed be Asian. Commentator Martin Wolf wrote about this in the editorial section of the Financial Times already in 2003:

Should [Asia's rise] proceed as it has over the last few decades, it will bring the two centuries of global domination by Europe and, subsequently, its giant North American offshoot to an end. Japan was but the harbinger of an Asian future. The country has proved too small and inward-looking to transform the world. What follows it-China, above all-will prove neither. . . . Europe was the past, the US is the present and a China-dominated Asia the future of the, global economy. That future seems bound to come. The big questions are how soon and how smoothly it does so.

The merry-go-round of history will continue; the reports of history’s death, as charming as they are, have been greatly exaggerated. The West must engage the reality of a pirouetting history and reject grandiose narratives that hail liberal democracy’s victory at history’s finish line into a 1000-year utopia of eternal domination.