The Grand Go-Board

While the Collective West fights short-term Chessboard battles, the Collective Rest build multipolar connectivity on the Global Go-Board.

Go is an ancient Chinese strategy board game. Unlike Chess, where the goal is to impose regime change by slaying the opposing king, in Go victory is attained by building large alliances and surrounding and capturing more territory than your opponent. The geopolitical implications of Chess vs. Go thinking are reflected in the different approaches leaders in the Collective West vs. Collective Rest-of-the-World are taking in Global War 6. Although BRICS+ geopolitical strategists may from time to time glance at The Grand Chessboard, they are far more comfortable implementing their own “Grand Go-Board” strategy.

Last week in Beijing, Chinese diplomat Wang Yi hosted a peace summit between Iran and Saudi Arabia, cementing their agreement to reopen diplomatic relations. Commitments were also given by the two Middle Eastern regional powers to stop their proxy wars in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq - and most urgently in Yemen. Over the past year, both Iran and Saudi Arabia have been holding intense negotiations to join the Collective Rest’s showcase BRICS+ economic order. But their smouldering conflict placed a ceiling on actual ascension of either nation, along with several of their neighbours.

Reaction in the US and Israel was muted. Perhaps they were fearful of the optics of launching an overt smear campaign against a peace deal? This might have led some observers to the conclusion that the West actually desired and even stoked the Sunni-Shiite conflict in a divide-and-rule Middle Eastern strategy.

With this move China seems to have effortlessly played a masterful Go move. If peace is indeed given a chance, the entire map of in the Middle East could flip to the BRICS+ bloc. The one major exception is, of course, Israel, which may soon find itself in a tactical BRICS+ encirclement. Luckily it’s only an economic alliance and not (yet) a military bloc. This geopolitical development has to be particularly painful for the US after investing 20 years and trillions of dollars in a futile campaign to democratize the Middle East.

But a deeper look at the Middle East example also shows that Go strategy cannot prevail all alone. China’s soft-power Go moves in the Middle East was only possible because of the much more mundane Chess game Russia has played in Syria in the preceding years.

Back in 2011, struggling in the aftermath of President Bush’s direct regime change operation in Iraq, President Obama chose a lighter-touch Chess move—indirect regime change—to checkmate the Syrian “king” and assembled an impressive coalition to execute it:

<…> ten years ago, NATO, the Gulf Cooperation Council, Turkey and Israel began a coordinated campaign of regime change against President Bashar al-Assad and the destruction of Syria. This has led to the death of over 500,000 people, millions of refugees, destroyed infrastructure and an economy in crisis. Despite numerous political manoeuvres, this alliance against Syria catastrophically failed and could not achieve regime change. Not only did Assad survive the onslaught, but the geopolitical situation dramatically changed as a result.

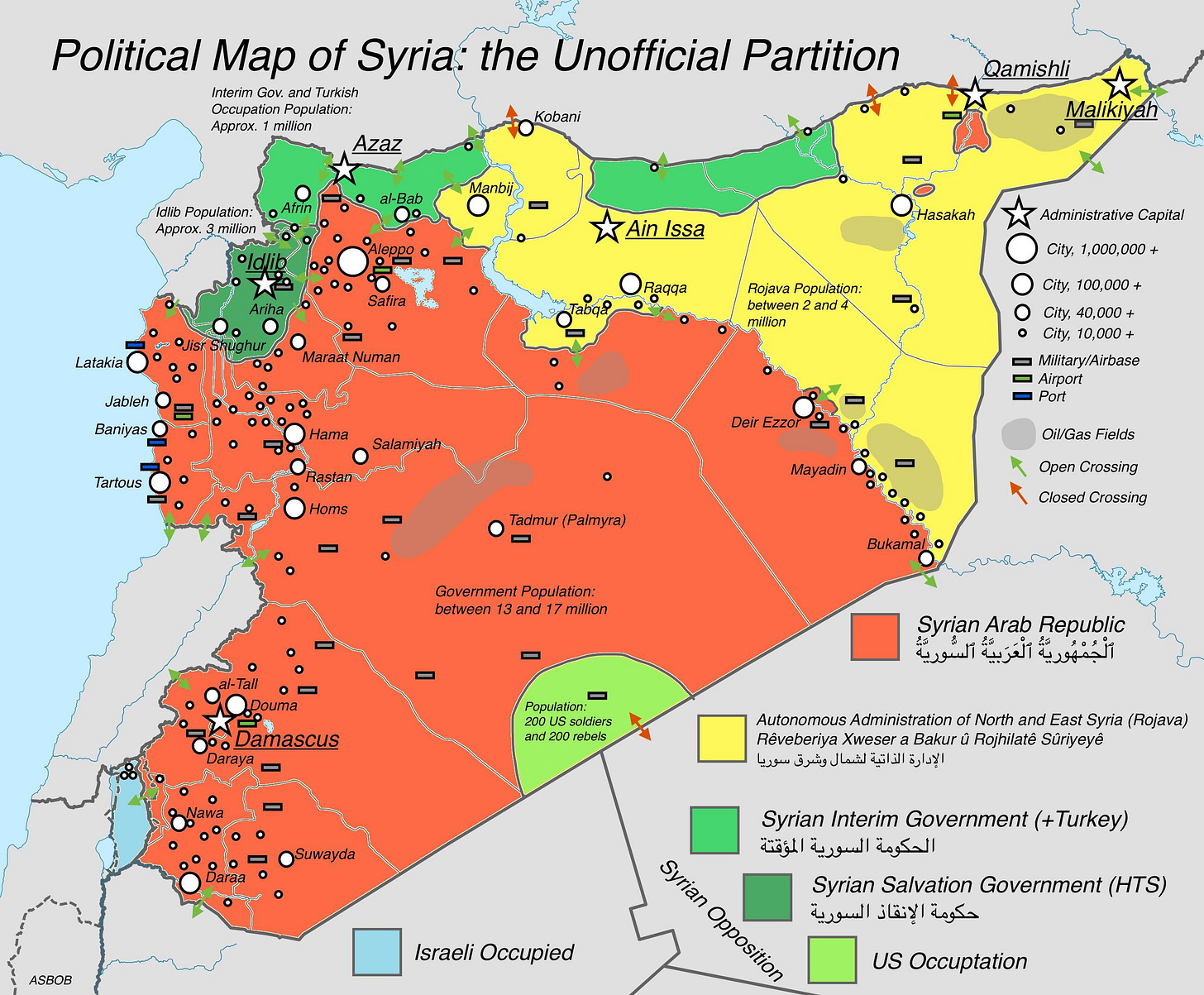

But Russians are renowned for their capabilities in Chess and it may be their successful defence of al-Assad which one day will seen as tolling the death knell of an already declining American-led Liberal World Order. But Syria was far from an outright Russian victory. While America failed to topple al-Assad, they do currently occupy a large portion of Syria, which by sheer coincidence, happens to contain many oil fields. Current Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense Dana Stroul admitted this back in 2019:

Resorting to classically colonial rhetoric, Stroul casually noted that “one-third of Syrian territory was owned via the U.S. military, with its local partner the Syrian Democratic Forces.”

She made it a point to stress that this sovereign Syrian land “owned” by Washington also happened to be “resource-rich,” the “economic powerhouse of Syria, so where the hydrocarbons are… as well as the agricultural powerhouse.”

This US occupation of Syria also provides ammunition to Russian information warfare efforts. Why does the Rules-based order condone an American occupation in faraway Syria yet condemns Moscow’s control over the Russian-speaking resource-rich Donbass? The common ground between the Chess-inspired US and Russia seems to be their proclivity towards occupying square kilometres of land.

Russia’s on-going successful defence of al-Assad has no doubt impressed Saudi leaders, who are wise enough to know that America’s crusade against authoritarianism may one day come knocking at their door, especially given their vast oil reserves. And so Russia’s traditional mastery of geopolitical Chess opened the door for China being able to flip the Saudi Go stone from West to Rest. As Russia battles the Collective West in classic hard-power Chess struggles in Syria and Ukraine, the larger Collective Rest is playing Go across the entire globe. They are scoring well in South America and Sub-Saharan Africa, though expansion of thin economic orders such as BRICS+ and China’s One Belt, One Road initiative.

As China starts peace overtures in Ukraine, one nightmare scenario must be haunting the West. After investing so much into dominating the Middle East, China was able to flip this region with a effortless Go touch. What if lightening strikes twice and an eventual peace deal compels Ukraine—facing a catastrophic defeat—to not only foreclose on any future membership in NATO or EU, but worse, to agree to join BRICS+ and OBOR, in return for Russian concessions?

The smooth space of Go meets the striated space of Chess.

The Go vs. Chess dualism was articulated in Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s (D&G) ground-breaking 1980 work of postmodern philosophy, A Thousand Plateaus:

Chess is indeed a war, but an institutionalized, regulated, coded war with a front, a rear, battles. But what is proper to Go is war without battle lines, with neither confrontation nor retreat, without battles even: pure strategy, whereas chess is a semiology. Finally, the space is not at all the same: in chess, it is a question of arranging a closed space for oneself, thus going from one point to another, of occupying the maximum number of squares with the minimum number of pieces. In Go, it is a question of arraying oneself in an open space, of holding space, of maintaining the possibility of springing up at any point: the movement is not from one point to another, but becomes perpetual, without aim or destination, without departure or arrival. The “smooth” space of Go, as against the “striated” space of chess.

The distinction between D&G’s concept of smooth and striated space is crucial for grasping the deeper significances of the Go vs. Chess binary. Smooth space is one of open vistas and freedom of movement. An ocean, a desert, or pastoral lands are examples. An urban environment with its channelled means of mobility or an agricultural field divided by stone walls are striated spaces. In war, often an army on the offensive seeks smooth space, wide fields for their tank battalions to sweep across. Forces on the defensive seek to striate smooth space. A river is the classic line of defence as its windings striate the smooth space of rustic meadows. Trenches, fortresses, or urban buildings are striated spaces of protection against attack. In naval strategy, access to the smooth open seas is a vital objective. Linking island chains or controlling maritime choke points creates striated space designed to deny your opponent access to oceanic smooth space.

D&G emphasize that smooth or striated space is never absolute, they always combine, it’s their relative ratio that is crucial. Again from A Thousand Plateaus:

Smooth space and striated space—nomad space and sedentary space—the space in which the war machine develops and the space instituted by the State apparatus—are not of the same nature. No sooner do we note a simple opposition between the two kinds of space than we must indicate a much more complex difference by virtue of which the successive terms of the oppositions fail to coincide entirely. And no sooner have we done that than we must remind ourselves that the two spaces in fact exist only in mixture: smooth space is constantly being translated, transversed into a striated space; striated space is constantly being reversed, returned to a smooth space.

While at first glance the gridded nature of the Go-board and Chessboard are similar, through smooth and striated space analysis, their differences become clear.

The chessboard functions like a striated urban space—an alternating pattern of squares demarcate travel corridors. Mobility across the board is subject to strict rules-based constraints that are embedded into the rigid hierarchical identities of each piece. The Queen may have much more mobility than a pawn but is still subject to striated space restrictions created by rules. The delineated Chessboard pattern resembles the intertwined threads of a woven fabric when revealed by a close up view.

In contrast, Go-boards feature a gentle crisscross similar to the virtual latitude and longitude lines lain across smooth oceanic space. Go stones have no individual identity outside of their white or black team signal. During play, Go stones are placed over the intersection of horizontal and vertical lines and have no mobility. This mimics the placement of columns on an architectural plan’s grid line intersections. Any stone may be placed on any free grid line crossing. Value is attributed to a stone by its positional potential to interconnect and form larger groupings of stones that may work to encircle opposing stone arrays. A Go-Board resembles the smooth space of felt, which D&G describe as the “anti- fabric” because it "implies no separation of threads, no intertwining, only an entanglement of fibers.”

Chess is the unipolar game par excellence, pursuing a war of attrition until the challenger king is slain (checkmated). The singular focus of Western Chess-think is manifested when complex geopolitical events are personalized into a simple bad-guy-du-jour narrative such as, “Putin’s brutal and unprovoked war” The same evildoer trope was used against Saddam, al-Assad, Kadhafi, and increasingly Xi. High-intensity checkmating operations on a bad guy may be required from time to time but this narrow focus carries the risk of obscuring gathering storms on the grander global board.

In contrast, Go is a multipolar game where the winners must multitask by managing many low-intensity conflicts across different Go-board regions. With each capture of territory, more poles are interconnected, each reinforcing the other. There is no need to destroy your enemy, only to flip and control as much enemy territory as possible. The multipolar order expands thanks to the intricate arraignment of its Go stone multiplicity, not each stone’s individual strength.

Perhaps the West prefer chess because they believe their much smaller Golden Billion populations consist of so many Queens, Rooks, Bishops and Knights, while they see the seven billion Collective Rest as just so many pawns. In addition, many Collective Rest elites are controlled by, or highly sympathetic to, the West. At the same time the question of identity—immutability or flexible—is roiling Western conversations. Should Queens renounce their privilege and agree to move one square at a time like pawns?

Go Navy—China’s quest for blue-water smooth space

A recent Wall Street Journal article, while never mentioning Go, certainly brings to mind the image of Chinese leaders sagely gazing over maps of the Spratly Islands Archipelago in the South China Sea. and calmly planting Go stones on the Paracel Islands, Subi Reef, Mischief Reef, and Fiery Cross Reef.

China’s gradualist approach has often confounded its opponents, leaving them uncertain about whether, when and how strongly to respond without escalating tensions. “That’s the long game that they often play,” the U.S. Navy’s 7th Fleet Commander Vice Adm. Karl Thomas said in an interview last year. “They will build a capability—it’s there and they’ll just incrementally increase their presence.”

While events are progressing well for China in the Spratly Islands, the ultimate test of the Go vs. Chess struggle between Rest vs. West will occur on Taiwan, which is the keystone of the First Island Chain containment strategy. This island chain acts as a oceanic trench, buttressed together to pin Chinese naval power into a striated coastal zone. Through control of the “unsinkable aircraft carrier Taiwan,” (or Formosa as Portuguese mariners named it) American strategists have long sought to deny China wartime access to the vast smooth spaces of the Pacific Ocean. As General Douglas Macarthur reported in his Farewell Address to Congress in 1951:

I have strongly recommended in the past, as a matter of military urgency, that under no circumstances must Formosa fall under Communist control. Such an eventuality would at once threaten the freedom of the Philippines and the loss of Japan and might well force our western frontier back to the coast of California, Oregon and Washington.

While the People’s Republic of China must have military control over Taiwan to develop its full maritime power potential—it does not necessarily need political dominance. Both sides will be eager to avoid a Ukrainian-style tragedy. So one compromise would be an “Independence-for-Naval Bases” deal where Taiwan demilitarizes and grants the Chinese Navy basing rights while China grants some sort of political independence for Taiwan. Once past the First Island Chain, China will get to work on cracking the second.

Capitalist Go or Feudal Chess?

Geopolitical power in a capitalist system flows from the pipeline, the sea route, the rail line, the digital connection. in short from infrastructure facilitating interconnecting flows of raw materials, fuel, food, factory goods, labour, and capital all driven by an unquenchable human desire to consume. The smooth space thinking needed to dominate a Go-Board is, for better or worse, capitalistic. Sanctions, boycotts, barriers, seizure of currency reserves are attempts to obstruct capitalist flows with boundaries or barriers. Chess requires a hierarchical feudal mentality—striating economic space to frustrate the flows. Too many sanctions can stymie and increase friction within the capitalist machine to the point of inflationary blowback, which in turn can destabilize banking systems. Instead of the Ruble turning to rubble, Western banking is tanking.

Karl Marx in the Communist Manifesto recognized these Go-Board capitalist qualities, he could have been analysing a game of Go when he said:

The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases [capitalism] over the entire surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere.

Marx goes on to highlight capitalism’s dislike of feudal barriers,

[Capitalism], <…> by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilisation. The cheap prices of commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians’ intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate.

How ironic would it be for the Collective West, which owes it preeminent global position to its historic control over the capitalist accumulation machine, to lose its global hegemonic position due to the Collective Rest’s better understanding of the underlying smooth space logic of capitalism?