Harmonizing the Trinity of Victory

Military strategy in Ukraine and Palestine through the lenses of two Prussian military geniuses: Carl von Clausewitz and Hans Delbrück.

When a nation goes to war, she tempts enemy incursions into her territory. During the post-WW2 era, the US waged wars against North Korea, Vietnam, Grenada, Iraq, Panama, and Afghanistan, yet none of these nations actualized their potential to attack the US. America wisely chose to go to war against weak countries, far away from her borders. Despite ultimately achieving victory in several cases, her adversaries either lacked the means or the will to strike America’s mainland. Hitting the US was not part of their winning grand strategy or theory of victory.

Since Russia's Kharkov offensive, Ukrainian campaigners have demanded the “right” to strike deep into Russia with long-range missiles supplied by the West. Throughout the war, Ukraine has regularly attacked Russian territory with drones and artillery. Ukraine has damaged Russia's oil infrastructure and targeted civilians in Belgorod, in addition to engaging in artillery duels against Russian military targets in the border regions. Ukraine recently struck the Russian missile early warning system (MWS) radar stations near Armavir and Orenburg, and an antenna in Crimea that warns of nuclear strikes. In fact, these radar systems also cover Iran, so these raids may be preparation for Western escalation in the Persian Gulf.

As most Western powers line up to publicly authorize Ukrainian cross border strikes on targets and people in Russia, many emotionally patriotic but frustrated Russians are demanding their government take much stronger action against both Ukraine and the West. As of this writing, the West has limited permissible attacks on Russia to artillery barrages, which typically have less than a 40 kilometre range.

With this permission granted, over the past few days, Ukrainian forces have destroyed several important targets within the Russian border areas: an S-400 air defense system, a warehouse of Iskander missiles, and a military convoy. There seems to be a temporary shift in battlefield momentum, with Russia’s advances slowing and Ukraine scoring more successes.

In response, Russian President Putin displays a cool and slightly autistic aura, and with laser-like intensity concentrates on the economic and diplomatic moves necessary to achieve victory.

Luckily for us today, the strategy of war falls into well-worn historical grooves that are chiseled by a universal human nature. By focusing on the highest levels of strategy and political policy of the past, today’s incessant jumble of details and particulars falls into order.

According to Prussian strategist Carl von Clausewitz’s trinitarian concept, all wars feature an irrational and hate-filled populace (passion) being harnessed by a rational and planning government (reason) supporting a military buffeted by probability and random happenstance (chance).

As we will see, there are two primary typologies of grand strategies: a war of annihilation and a war of exhaustion. A war of annihilation is what war is usually imagined in the popular mind: a great army marches into the enemy nation and destroys her forces. Afterwards the victorious general sets his terms for peace. This strategy relies primarily on military might to quickly defeat an enemy.

Wars of annihilation can prove very costly, demanding significant differentials in military potential between the two armies and requiring substantial resources to execute. They also entail considerable risk, as evidenced by Napoleon's ill-fated advance into Moscow, which ultimately resulted in defeat during his retreat from Russia.

Clausewitz’ disbelief in the possibility of the total annihilation of Russia led indirectly to Prussian historian Hans Delbrück’s theory of wars of exhaustion. Here, cautious military assaults combine with economic, diplomatic, and informational attacks aim to wear down an opponent's will to resist. These wars take much longer to execute, and the resulting peace deals may offer more modest gains for the victorious side.

Clausewitz, primarily a philosopher of wars of annihilation, also outlined a theory of victory for defeating Russia—later successfully applied by Germany in WWI. Today the West echoes this strategy, albeit with much less success than the Kaiser knew.

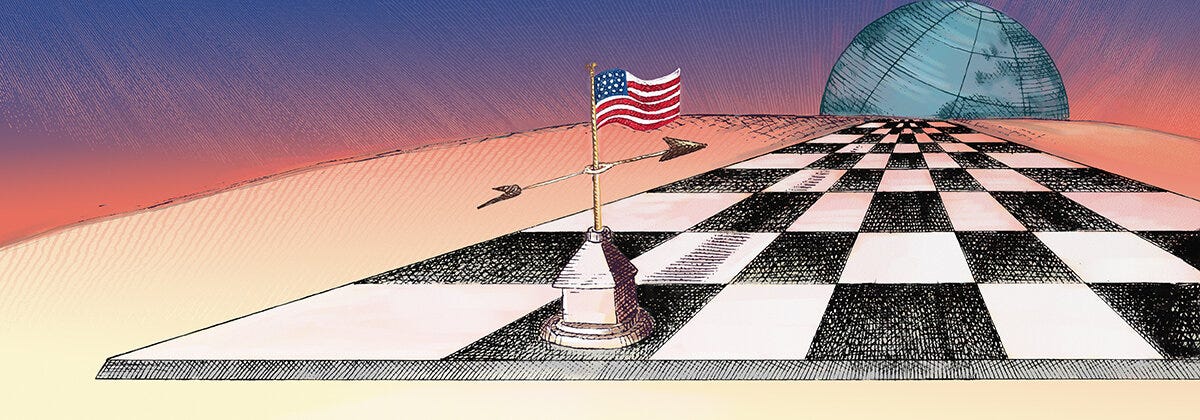

Today’s wars in Ukraine and Gaza can be best understood, not by only reading the day-to-day headlines, but through a deeper comprehension of grand strategy, including theories of victory based on Clausewitz’s trinity, and Delbrück’s concepts of wars of annihilation and exhaustion.

Grand Strategy

For a nation-state, whether at peace or war, developing grand strategy is the primary responsibility of political leadership. 20th century British military theorist Basil Liddell Hart emphasizes the non-military components of grand strategy in his succinct definition found in his classic, Strategy:

For the role of grand strategy—higher strategy—is to coordinate and direct all the resources of a nation, or band of nations, towards the attainment of the political object of the war the goal defined by fundamental policy.

Grand strategy should both calculate and develop the economic resources and manpower of nations in order to sustain the fighting services. Also the moral resources for to foster the people’s willing spirit is often as important as to possess the more concrete forms of power. Grand strategy, too, should regulate the distribution of power between the several services, and between the services and industry. Moreover, fighting power is but one of the instruments of grand strategy which should take account of and apply the power of financial pressure, of diplomatic pressure, of commercial pressure, and, not least of ethical pressure, to weaken the opponent’s will. A good cause is a sword as well as armour. Likewise, chivalry in war can be a most effective weapon in weakening the opponent’s will to resist, as well as augmenting moral strength. (p. 322)

Grand strategy is deployed against an opponent—just as in sports a game plan is produced to defeat a rival team. This is a dialectical process as the opponent develops a counter-strategy. Each side must weigh its ends and means and develop an approach to international competition. Since surprise and deception are paramount values, a paradoxical logic governs strategic thought. For example, in normal life, one would choose the best road and weather conditions for traveling. In war, the most precipitous mountain pass and foggy weather conditions can be the most propitious for launching an attack.

In normal times, economic trade relations between two peoples can often bring win-win benefits to both sides. But in a struggle between two belligerents, where the goal of each side is a win-lose outcome, boycotts, hard sanctions, blockades, and economic sabotage often result in lose-lose outcomes for all involved.

The Kremlin’s post-Soviet grand strategy can be inferred through Russia’s actions over the past 25 years. After Russia retreated to her own borders, it had two key goals: to integrate economically with the West while simultaneously defending her near periphery from Western co-option. These goals must have seemed complementary, as the West benefited from cheap and plentiful Russian resources, and so surely their desire to intervene within Russia and her near sphere of influence would diminish? This assumption was false.

The idea of a unified West was Russia’s key misconception. The US and EU have vastly different interests. As explained in "Ordered Off the World-Island," the US must never allow Germany and Russia to grow close.

As Margaret Thatcher once pointed out in a different context, “Russia has everything: oil, gas, diamonds, platinum, gold, silver, timber, marvellous soil, but has been poor.” Russia is also gigantic. And there is not only a long history of British Russophobia, but many nationalities from the former Russian Empire’s periphery still hold powerful ethnic animus towards all things Russian. And so in Georgia, Crimea, and finally Ukraine, Russia had a choice between protecting her near abroad or foregoing economic links with the West. She chose the latter, and in doing so, her post-Soviet theory of victory collapsed.

Trinity of Victory

In “On War,” Clausewitz presents his trinity of war—passion, chance and reason—which are embodied by—the people, the military and the government—as a universal description of the art of war:

A paradoxical trinity—composed of primordial violence, hatred, and enmity, which are to be regarded as a blind natural force; of the play of chance and probability within which the creative spirit is free to roam; and of its element of subordination, as an instrument of policy, which makes it subject to reason alone.

Since war is oppositional, strategy comes down to defending the interconnectedness, health and balance of your own trinity while seeking to undermine and destroy the coherence of your enemy’s. The plan to do just this is called a theory of victory.

British-American military strategist Colin Gray, who passed away in 2020, uses the terms “theory of war” and ‘theory of victory” interchangeably. Despite defense contractors CEOs prioritizing profits, typically a nation seeks victory when fighting wars. To avoid confusion I will exclusively use the phrase “theory of victory.” In his book War, Peace, and Victory, Gray explains:

A theory of [victory] explains how a particular war can be won. A theory of [victory] is a special, restricted case of grand strategy. It does not explain why a war should be waged, nor does it specify what the war aims should be—those are the realms of policy. A theory of [victory] explains how a particular country or coalition can be beaten at a tolerable cost.

A theory of victory is a statesman’s version of a writer’s précis—a brief synopsis of how victory will be achieved. For example, Gray explains the British theory of victory for World War 1:

In 1914 the British government intended that, <…>, allies in Europe would function as Britain's "continental sword." In the fall of 1914, the British theory of war envisaged that the allied French and particularly Russian armies would fight Germany (and Austria-Hungary) to a standstill during two or more years of campaigning. The British all-volunteer New Armies raised by Lord Kitchener—the minister of war and the dominant figure in war policy—were expected to peak in their strength in early 1917, by which time all of the great continental powers, enemies and allies alike, would be exhausted.

The German theory of victory in WW1 was to avoid a two-front war by quickly defeating France in a war of annihilation in the west, and then destroying Russia in a second war of annihilation in the east. Germany came close to victory in France but got bogged down at the First Battle of the Marne. Nevertheless, and of great interest to future generations, they did manage to defeat Russia, but through a war of exhaustion.

Russia’s initial theory of victory in Ukraine was to wage a shock and awe political invasion that would give the Ukrainian political class cover to agree to neutrality (renounce future NATO membership), grant autonomy to the Donbass within Ukraine, and eventually abandon Crimea. However, this accord was vetoed by the West, who encouraged Ukraine to fight on.

In such a war for limited aims, stirring passion within the Russian forces was a problem. While the Ukrainians had been trained for decades to hate Russians, for the typical Russian soldier, it was difficult to muster enough animus to kill their Slavic brothers. Once the West stepped in and blocked the peace deal, then flooded Ukraine with weapons, Russians developed a hatred of the decadent West which fuelled the war effort with little help from government propaganda.

In the aftermath of the failed peace deal in the Spring of 2022, Russia adopted a second theory of victory. Through a war of attrition, Ukraine and the West would be demilitarized, and increasing levels of economic destruction of Ukraine would force the West to abandon the war effort. Russia would annex areas of Ukraine, with the rump being forced to accept a pro-Russian puppet government. In an attempt to drive a wedge between Ukraine’s government and her people/military, Russia is highlighting Zelensky’s dubious presidential legitimacy.

Since the end of WW2, the West had its own theory of victory against Russia, partly based on the 19th-century Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz’s comment on Russia, and buttressed by the example of Imperial Germany’s successful campaign against Russia in 1917.

Clausewitz on how to defeat Russia

Clausewitz is well known for advocating wars of annihilation, where the enemy's military center of gravity is targeted and destroyed. However, Clausewitz's comments on Napoleon's failure in Russia opened the way to a second conception of war.

[Napoleon’s] campaign failed, not because he advanced too quickly and too far as is usually believed, but because the only way to achieve success failed. Russia is not a country that can be formally conquered—that is to say occupied—certainly not with the present strength of the European States and not even with the half-a-million men Bonaparte mobilized for the purpose. Only internal weakness, only the workings of disunity can bring a country of that kind to ruin. To strike at these weaknesses in its political life it is necessary to thrust into the heart of the state. Only if he could reach Moscow in strength could Bonaparte hope to shake the government’s nerve and the people’s loyalty and steadfastness. In Moscow he hoped to find peace; that was the only rational war aim he could set himself.

In occupying Moscow, Napoleon assumed the Russians would quit. However, the vast size of Russia and the continued functioning of the people, armed forces, and governmental triad meant his work was only beginning. Napoleon had exhausted himself in reaching Moscow; he needed a large enough force to continue the war north towards the Russian capital, St. Petersburg. Instead, Napoleon expected the Russians to act as rational Europeans who would admit defeat and submit to his terms after losing such a prestigious city. Nothing could have been more wrong. According to Clausewitz:

We maintain that the 1812 campaign failed because the Russian government kept its nerve and the people remained loyal and steadfast. The campaign could not succeed.

During World War I, Imperial Germany applied the lessons of Clausewitz effectively. They battled Tsarist Russian forces in Eastern Europe but sought a decisive victory by overthrowing a wobbly Tsarist regime. As with all empires under stress, the periphery zones are the most unstable. Germany aligned with revolutionaries from disgruntled nationalities of the Tsarist Russian periphery.

Living in exile in Switzerland during the great war, frustrated revolutionary Vladimir Lenin’s anti-Russian proclamations caught the eyes of German authorities. From Lenin: Life and Legacy by Dmitri Volkogonov:

In it [Lenin] penned the phrase that was to become sacrosanct in Soviet historiography: ‘From the point of view of the working class and the toiling masses of all the peoples of Russia, the lesser evil would be the defeat of the tsarist monarchy and its troops, which are oppressing Poland, the Ukraine and many other peoples of Russia.’ He went further in November 1914 when he wrote, “Turning the present imperialist war into civil war is the only proper proletarian slogan.’?

<…>

In a letter of 17 October 1914 to one of his most trusted agents, Alexander Shlyapnikov, then in Sweden, Lenin wrote: ‘. . . the least evil now and at once would be the defeat of tsarism in the war. For tsarism is a hundred times worse than kaiserism . . . The entire essence of our work (persistent, systematic, maybe of long duration) must be in the direction of turning the national war into a civil war.

While Lenin remained in Zurich, the Tsar was overthrown in March of 1917 in a moderate bourgeois revolution. Nonetheless, Russia continued to fight. The Germans were not satisfied and in April chartered a train from Zurich with 32 Russian emigrants on board.

The German chartered train was provided by Kaiser Wilhelm II with the aim of furthering the Russian Revolution. In one of the wagons sat none other than Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, better known as Lenin. With German help, Lenin left his exile in Switzerland and, a week later, reached his destination: Petrograd, which would later be renamed to Leningrad then changed back to today's Saint Petersburg.

<…>

Berlin's strategy was clear: Lenin and his Bolsheviks were meant to destabilize Russia thereby — in the middle of the First World War — easing the burden of fighting on the Eastern Front. The German Empire was relying on an old rule of diplomacy: The enemy of my enemy is my friend. And the plan worked.

The idea originated with a man who took the communist nom de guerre "Parvus," or the little one: Israel Lazarevich Gelfand. He was a Russian Jew who at the end of 1914 had already been using his influence to offer the German ambassador in Constantinople an alliance of "Prussian bayonets and Russian proletarian fists." He claimed that the interests of Germany and the Russian revolutionaries were identical. After some initial skepticism, he was granted an audience in Berlin.

<…>

Gelfand's cunning plan eventually bore fruit. On November 7, 1917, a coup d'état went down in history as the October Revolution. The interim government was toppled, the Soviets seized power, and Russia later terminated the Triple Entente military alliance with France and Britain. For Russia, it was effectively the end of the war. Kaiser Wilhelm II had spent around half a billion euros ($582 million) in today's money to weaken his wartime enemy.

The Germans reaped huge dividends from their minimal investment in the Bolsheviks. Once in power, Lenin sued for peace with Germany. The German-friendly Treaty of Brest-Litovsk soon followed which ended the war on the Eastern Front and allowed Germany to turn her full attention westward. A month later Lenin ordered the assassination of the Tsar, his ministers, along with his entire family.

Robert Tucker, in his book “Stalinism: Essays in Historical Interpretation,” carefully touches on the ethnic nature of the Bolsheviks. Writing in post-WW2 America, strong taboos blocked any reinforcing of the Judeo-Bolshevik slur. Nevertheless, there was an undeniable high concentration of peripheral nationalities among the 1917 revolutionaries in Russia. And why not? If they felt particularly oppressed by a Tsarist Russian occupation, why wouldn’t they join their equivalent of Hamas?

It is generally known that there were quite a few Jews, Latvians, Poles, Finns, and members of the various nationalities of the Caucasus, as well as many other “aliens” in the membership of the revolutionary parties. This was natural, since, in addition to the various forms of social oppression, these people of the Russian Empire also suffered from national oppression, something that most people are particularly sensitive to. (p. 221)

Due to the relatively high numbers of working-class Russians who made up the rank-and-file of the revolutionary armies, Robert Tucker hesitates to call the Russian revolution a “victory of the national borderlands over Great Russia.” Nevertheless, ethnic groups from the national borderlands did dominate the revolutionary elite. Germany successfully stressed pre-existing fault lines within Imperial Russia to the breaking point. In Clausewitzian terms, they toppled the Russian trinity by breaking the bonds between the people and the government.

They did this by promoting peripheral nationalities over the core Russian majority. A glance at the ethnicities of the various Soviet leaders tells the story. Lenin was Jewish, Stalin was Georgian, Malenkov was Russian but failed to consolidate power, Khrushchev and Brezhnev were Ukrainian, Andropov was Jewish, Chernenko was Ukrainian. The first unambiguously Russian leader to establish his rule over the Soviet Union was Mikhail Gorbachev, who then liquidated it less than seven years after taking power.

Today, the Western anti-Russian alliance is also highly overrepresented by the same ethnic nationalities, with Ukrainians, Jews, Latvians, Poles, Finns, and Caucasians. But after the collapse of the Soviet Union, a weakened Russia retreated within her borders, relinquishing many of her Soviet possessions, to a more cohesive and manageable core.

And yet, post-Soviet Russia was still incredibly diverse, ruling many non-Russian subjects. The West saw this diversity as Russia’s weakness. After President Putin came to power, he was able to quash the irregular war in Chechnya, fueled in part by Western intelligence agencies. The West has continually agitated to further the momentum of the Soviet fractures, by working to fragment the Russian Federation into even smaller bits.

The 21st-century Russian “revolutionary” who the West paid for and promoted was the mirror opposite of Lenin. After the failure of militarizing Muslim minorities in Chechnya, the West cleverly financed the ultranationalist Alexei Navalny, attempting to reverse the core/periphery disintegration dynamic. With Lenin, the periphery dominated the core. In contrast, Navalny’s ultranationalist ideology sought to establish a pure Russia free of minorities. Navalny’s intent was to repulse the non-Russian periphery into rebellion.

At the same time, pressure was applied from the now-free peripheral nations that escaped from the Soviet Union. The Baltic countries, along with Poland and Finland, have led the Russophobic charge in the 21st century. Descendants of former ethnics of the Russian Empire such as the Pole Zbigniew Brzeziński and innumerable Jewish neoconservatives with roots in the Russian Empire have kept the fire of hate against Russia burning brightly within the American foreign policy establishment.

If the maxim, “we are what we hate,” ever needed more confirmation, after a decade of anti-Putin tirades for imprisoning an opposition leader, the Russophobes in the US are trying to incarcerate the front-runner in the 2024 Presidential election.

To protect his Clausewitzian trinity, internally Putin has prioritized conservative values and patriotic populism. He promotes unity by granting Chechnya true autonomy in return for unconditional loyalty. But where Putin has truly shone is in forging links on the international level. In the words of Marx, Russia must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere. His no-limits partnership with China anchors the BRICS, which may grow to over twenty members this year. In addition, Russia is making great headway in the Sahel region of Africa, rudely booting out the neo-colonial forces of France and the United States. Putin’s emphasis on traditional values also makes him popular among anti-woke Western factions.

Putin is currently profiting from NATO sabre-rattling by re-establishing the moribund Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which includes Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. There is hope in pro-Russian spaces of an imminent deal with Afghanistan to provide military forces to fight on the Russian side in Ukraine. These troops would need corridors through Russian’s Central Asian allies to reach Russia by ground transport.

Clausewitz’s trinity promotes the use of ignorant, black-and-white emotionalist thinking to forge emotional solidarity between the state and the people in support of the war effort. Russia’s branding of the Ukrainians as Nazis allows her internally-targeted wartime propaganda campaigns to accomplish this task. However, government leadership must rise above this swamp of hysteria and remain in an intellectual domain of rationality and nuance. Dangerous situations arise when statesmen get high on their own hate-filled speeches and internalize the Manichean duality of good and evil.

The Bipolar Strategy of Exhaustion

Prussian historian Hans Delbrück classified all wars into two types: wars of annihilation or exhaustion/attrition. A war of annihilation is what most people conceive war to be: a sharp struggle decided by a decisive battle. These are the wars fought by commanders who dominate the greatest-of-all-time discussions: Alexander, Caesar, and Napoleon.

In their 2023 counteroffensive, the Ukrainians childishly attempted to win a war of annihilation against Russia. Their Western propaganda-inspired theory of victory was that armed with the most modern and powerful Western arms, brave Ukrainian infantry would break through the ragtag Russian forces, who, armed only with shovels, would fight as pathetically as the Iraqis did in 1991. After the Ukrainians reached the Azov Sea, Crimea would tumble next, and the annihilated Russian forces would limp back home and sue for peace. As is common throughout the history of human warfare, the limited Ukrainian means did not match their grandiose political goal of crushing Russia’s will to resist.

In contrast, the West does not wish to directly confront Russian armed forces and is conducting a war of exhaustion through the use of sanctions, boycotts, information warfare, gaslighting, and arming proxies such as the Ukrainians.

In Palestine, Hamas, as an insurgent, is by definition conducting a war of exhaustion against Israel. For Israel, it is less clear. Despite Israeli rhetoric, it is exceedingly difficult to militarily annihilate an even halfway competent insurgent group. And so, Israel is implementing a Gazan version of her Dahiya doctrine, which seeks to target civilians and their infrastructure. The goal is to “exhaust” civilian support for the insurgents. As Mao claimed, “the guerrilla must move amongst the people as a fish swims in the sea”; the Israeli goal, then, is to evaporate the civilian sea through a barrage of high explosives.

The problem for both Israel and the Palestinian people is that Hamas are not Palestinian nationalists. They are universalist Islamists who see their “sea” as all Muslims. If a few have to suffer for the many, so be it.

In US history, the 1991 Gulf War was a war of limited annihilation. The 2003 version was an attempt by the US to execute a proper war of annihilation, which failed due to the Iraqi forces fading into the woodwork and avoiding annihilation. What followed was a long war of exhaustion. Vietnam was a war of exhaustion on both sides—as was Afghanistan.

These two types are not strictly dichotomous. Delbrück refers to wars of exhaustion as “bipolar” since a general can switch from a patient defensive stance to a sudden attack, depending on the situation. Towards the end of a successful war of exhaustion, where the tired enemy refuses to surrender, it opens the way to a quick and sudden coup de grâce final battle of annihilation. The American Civil War from the Northern point of view was a long war of exhaustion, ending with the exclamation point of Sherman taking Atlanta and then marching to the sea.

A war of exhaustion combines military attacks with blockades, economic destruction, and the occupation of critical territory, all working in combination to exhaust the enemy. One key element of an exhaustion strategy is that it allows the nation to employ limited means to accomplish her goals. This strategy requires greater command skill and flexibility, as decisions are made on where and when to launch limited attacks and when to conserve forces in defense. Strategic patience is a must.

In Ukraine, Russia, through a combination of limited ground warfare and aerial attacks, is exhausting Ukraine’s manpower reserves and the West’s surplus military equipment, including air defense systems, artillery shells, guns, tanks, and armoured personnel carriers. By destroying the Ukrainian economy, Russia seeks to exhaust Ukrainians and their Western sponsors.

Russia’s Likely Response to Western Escalation

Ukraine’s current theory of victory is to escalate the situation to the point where NATO troops will act as their “continental sword” against Russia. Given NATO’s conventional war superiority, a large NATO intervention in Ukraine would almost certainly prompt Russia to respond with tactical and operational nuclear weapons in Europe. Any subsequent counter-strikes on Russian territory would trigger a massive attack on the United States. Just as Ukraine has the option of striking Russia, if the U.S. joins the war against Russia, U.S. territory may also be targeted.

Elites in New York, Washington D.C., Los Angeles, and Silicon Valley intuitively understand the meaning of “socialization of danger,” making a direct military intervention by the U.S. highly unlikely. Additionally, the U.S. is preoccupied with the conflict in Palestine and a potential war in East Asia.

Nevertheless, the prospect of nuclear-capable Western cruise missile strikes deep into Russia, combined with Ukrainian attacks on Russia’s early warning system, represents a dangerous escalation towards nuclear war. In response, Russia has conducted exercises with tactical nuclear weapons. The problem is that, outside of a few airbases being prepared to base F-16s, there are no good targets in Ukraine for a tactical nuclear strike.

If Russia were to break the nuclear taboo in Ukraine, it would likely benefit Israel, which faces significant challenges in the north. Already struggling with hapless Hamas, Israel would face severe difficulties if they attempted to invade Lebanon to root out Hezbollah. A few tactical nuclear devices would do the job effectively. However, in a conventional war, Israel's only option would be a brutal bombing campaign of civilian infrastructure around Beirut. This approach would likely shift global opinion even further away from the US and Israel and towards China and Russia.

Russia is better served to hold off on any nuclear action in Ukraine. However, if Israel uses nuclear weapons against Hezbollah, the rest of the world might then encourage Russia to follow suit in Ukraine and elsewhere.

In the meantime, Russia has brought down a US drone over the Black Sea using electronic warfare measures. This action will help soothe frustrated Russian hawks. Even high up in his temple of rationality, Putin must occasionally feed the emotional needs of the masses to keep his trinity stable.

The most likely tit-for-tat response to Western artillery systems killing Russians in Russia is for Russia to provide weapons systems to proxies around the world to hit Western targets. Recently, the Houthis in Yemen announced successful strikes on the nuclear-powered US aircraft carrier USS Dwight D. Eisenhower in the Red Sea. Circumstantial evidence confirms the strike, but no accurate reports of damage have been released. Additionally, Hezbollah has recently intensified its attacks in northern Israel.

The summer of 2024 may see increasing escalation as all sides seek to exhaust their enemies. Victory will not fall to the side that conjures a few spectacular events. If history is our guide, the side that manages to keep its Clausewitzian trinity in harmony while undermining its enemy’s cohesion will prevail.

Putins admission of the numbers of Russian losses surprised me. He must be very confident in support for the war to admit 10k a month's in total casualties.

If he is willing to confirm those kinds of numbers then it's clear recruitment is well ahead of those figures and Russia is building combat power continuously. It also seems Putin does not see an end anytime soon, still I feel the war grows short. Once Trump gets in and in Europe various right wing populists embed in parliament there will be a change in war policy, it will literally be supported only by the ex soviet/warpac states and Britain, and they will quickly fold when Trump glares at them. If we can avoid an escalation spiral before November then new possibilities will open.

exactly