Global War 6: Tariff Strife

Trump launches, then backpedals on a global tariff blitz primarily aimed at China. America's twin global roles—world cop and financial anchor—are burdens it must address to remain global hegemon.

Since the 1970s, the global order has rested on a grand bargain: the United States would supply the world’s reserve currency and, since the 1990s, serve as its unipolar military power—offering protection or provocation, depending on perspective. Today, that dual role is fraying. At the heart of it lies a hard truth: no nation, however mighty, can bear the weight of both financial and military hegemony forever. History moves in cycles—empires rise, rule, and recede. The U.S.-led system will eventually follow suit. This isn’t doom; it’s the rhythm of power.

Since the dawn of thought, humans have searched for shape in history’s storm—patterns that echo nature’s deep rhythms: the arc of the sun, the drift of seasons, the hush between birth and death. Civilizations, too, seem to breathe in cycles—rising, peaking, fading. This need to find order is more than curiosity; it is survival. Yet history is no wheel that turns of its own. It is not fate but memory—its echoes growing louder when we forget to listen. Studying these cycles is not surrender to what must be, but a warning that what has been may come again—unless we choose otherwise.

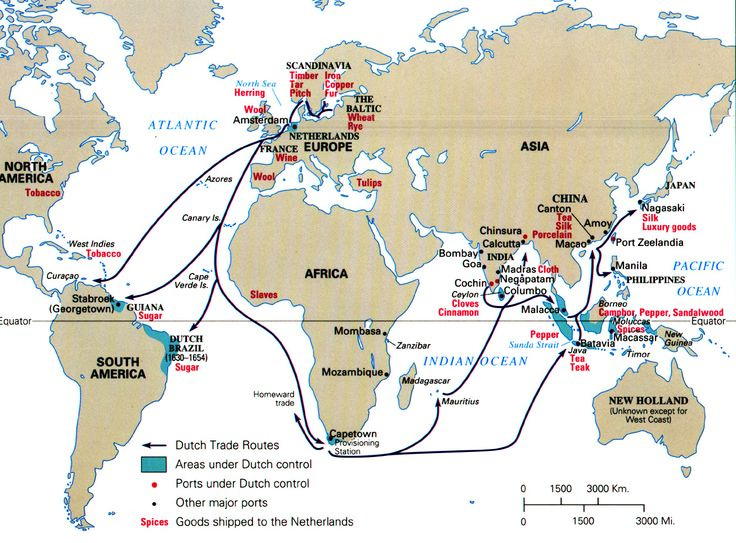

Among the many frameworks tracing the arc of global power, George Modelski’s Long Cycle Theory stands out for its sweeping clarity. Alongside Paul Kennedy’s concept of imperial overstretch and Immanuel Wallerstein’s world-systems analysis, Modelski offers a lens through which centuries of upheaval take on a discernible rhythm. In Long Cycles in World Politics (1987), he identifies five hegemonic cycles: Portugal (1516–1609), the Dutch Republic (1609–1714), Britain I (1714–1815), Britain II (1815–1945), and the United States (1945–present). Each cycle unfolds in two phases: an initial generation of ascendancy and relative order, followed by a decline marked by eroding legitimacy, rising challengers, and ultimately, a 25–30-year global war that ushers in a new order. The historical record lends weight to this structure, revealing power not as a permanent condition but as a tide that rises, crests, and inevitably recedes.

History’s great power shifts have often arrived not with a whisper, but with the thunder of global war. The first, from 1494 to 1516, saw Portugal rise through dominance of the Indian Ocean, outpacing Spanish land empires and Ottoman naval resistance. In the late 16th century, Dutch privateers chipped away at Spanish supremacy, their commercial fleets laying the foundation for a new order. Britain’s ascent, beginning in 1688 and culminating in 1714, checked France’s ambitions in the War of the Spanish Succession. A second British cycle, forged in the crucible of Napoleonic Europe from 1792 to 1815, ended with Russia’s pivotal stand in 1812 and Britain’s imperial zenith. Finally, the wars of American ascendancy—1914 to 1945—spanned two world wars, with the Soviet victory at Stalingrad crippling Nazi Germany, but it was the U.S. that emerged as the architect of the postwar global system.

What renders these wars truly global is not the sweep of their land campaigns—often anchored in Europe—but their reach across the seas. It was maritime power that transformed continental struggles into planetary upheavals. Control of oceans, trade routes, and distant colonies shaped the outcomes more than battlefield victories alone. Sea power served as the hinge of hegemony. Thus, while Russia and later the Soviet Union achieved pivotal land victories in Global Wars 4 and 5, their limited command of the seas barred them from ascending to global leadership. In the end, it is the power to project across oceans—not just to win on land—that crowns an empire.

Capitalism and Victory

If global wars crowned new hegemons, it was economic mastery of capitalism that paved their path to victory.

These wars did more than settle rivalries on land or sea—they revealed which powers had forged the most adaptive, expansive economic systems. In Global War 2, the Dutch didn’t merely scatter Spanish fleets; they unleashed a financial revolution that made military success possible. Amsterdam became the nerve center of global capitalism, pioneering stock exchanges and chartered trading companies that rewired the economic map. Their swift, shallow-draft ships stitched together vast commercial networks, moving spices, grain, and silver with unmatched speed and efficiency. Lean, innovative, and flush with capital, the Dutch outpaced lumbering empires rooted in land and crown. Naval supremacy was not the source but the expression of their economic power—proof that in the modern age, control of markets precedes control of guns.

Britain and later America perfected the fusion of war-making and wealth-making, while landbound empires lagged behind. In Global War 3 and again in the Napoleonic storms of Global War 4, Britain’s command of the seas—immortalized at Trafalgar—was no mere tactical edge. It shielded the forge of the Industrial Revolution. British steam engines, spinning jennies, and mechanized looms churned out goods at unprecedented scale, saturating global markets and drowning French artisanal production beneath waves of cheap manufacture. Even as Russia secured a decisive land victory over Napoleon in 1812, its modest navy left it trailing behind Britain on the world stage. Despite Russia's military triumphs on land, the crown of global leadership remained firmly in British hands, sustained by its economic and naval dominance.

In Global War 5, the United States brought the model to its industrial peak. Through Fordism and mass production, America unleashed an unrelenting torrent of tanks, ships, and aircraft, overwhelming the Axis powers. German factories roared, and Soviet forces shattered Hitler’s eastern front—but the U.S. wielded the ocean as its economic superhighway. Its unparalleled naval reach and manufacturing might enabled it to project power across continents, shaping a new global order. In the battle for hegemony, sea lanes, supply chains, and assembly lines proved as decisive as armies.

American Supremacy or Chinese Ascendancy?

History’s ebbing cycles often crystallize only in hindsight, yet the contours of Global War 6 are beginning to take shape today. At its core is the battle for global supremacy: can the United States extend its leadership into a second century, or will China rise to claim the mantle?

Eighty years after assuming post-war leadership, the U.S. faces pressure on two fronts. Domestically, a shrinking middle class and widening inequality threaten the social cohesion and political flexibility that underpinned its rise.

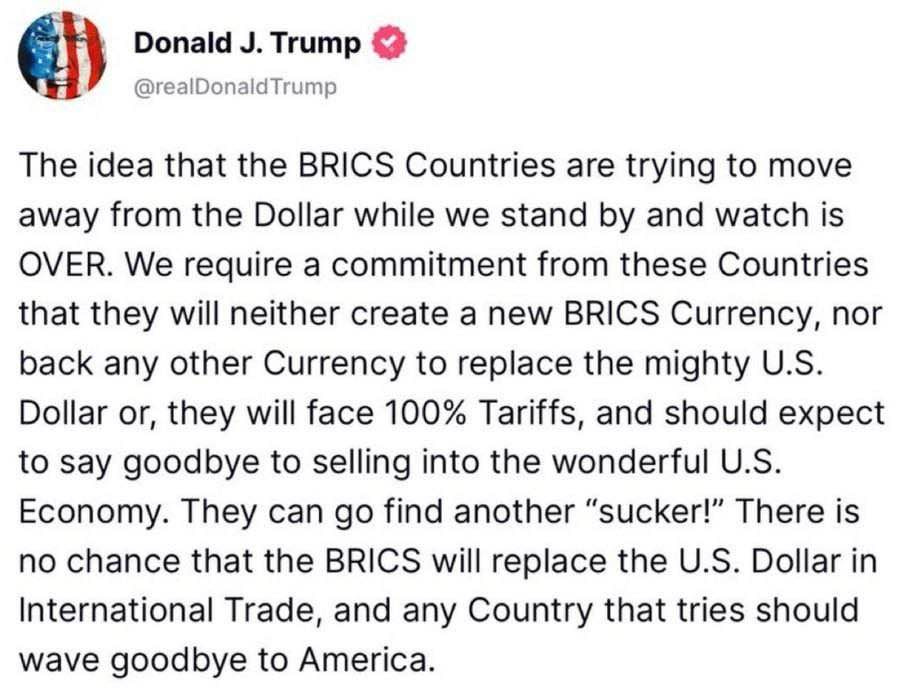

Internationally, a coalition of revisionist powers—China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea—are challenging the Western-led order. Meanwhile, BRICS nations like India, Brazil, South Africa, the Gulf Monarchies and Indonesia find themselves walking a tightrope, cultivating good relations with both sides as the global struggle unfolds.

In response, the U.S. has turned inward, prioritizing its own economic stability and security, much like a passenger securing their oxygen mask before helping others. This shift, though necessary for self-preservation, risks straining ties with long-time allies and complicating efforts to maintain global leadership.

The unravelling of open trade often signals the start of broader conflict. In 2022, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine set the spark. Within weeks, the West responded with sweeping sanctions—financial blockades that froze Russian assets and severed its ties to global markets. Russia swiftly adapted, pivoting eastward and establishing new trade routes. By April, the U.S. had escalated its involvement, providing Ukraine with intelligence and weaponry.

Global War 6 has now expanded into a global economic battlefield, with China at the forefront. Recently, the U.S.-China trade war escalated to new extremes, with tariffs reaching 145% on Chinese imports and 125% in retaliation. Beijing dismissed the move as “a joke in the history of world economy,” but the intent is clear: to disrupt China’s trade flows, much like navies once interrupted shipping lanes. However, if key allies start gravitating toward China’s economic orbit, the global power balance could shift dramatically.

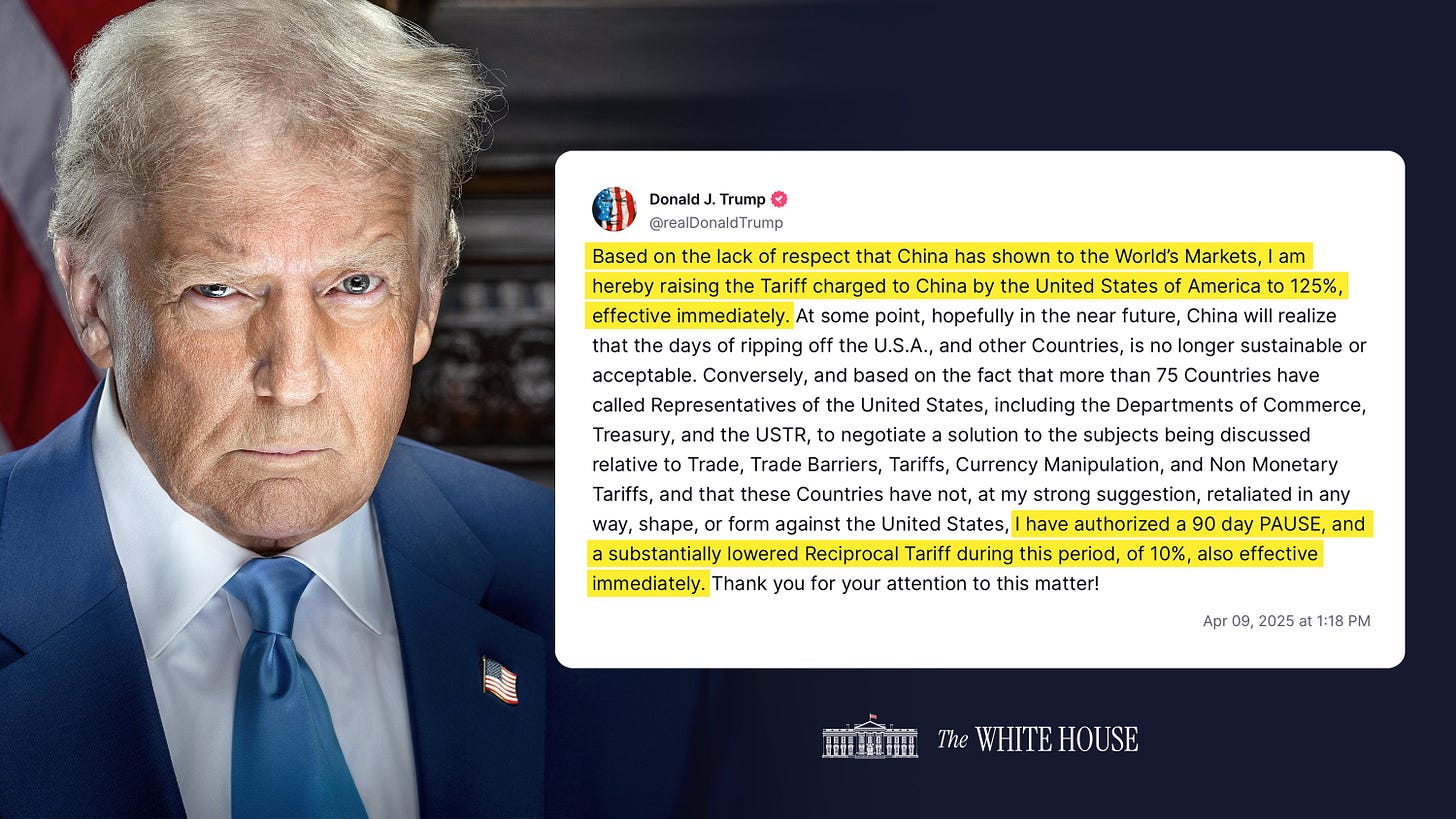

Trump’s Probing Attacks on Trade

A well-timed retreat can often shift the future tides of war. On April 9, 2025, President Trump eased back from his initial global tariff salvo on April 2, scaling most duties down to 10% for 90 days—except for China’s, which soared to 145%. Markets reacted with a surge, fuelled by hopes of de-escalation. Critics dismissed it as a “phony trade war,” while supporters saw it as classic Trump: a high-stakes bluff, a signature “Art of the Deal” move, laying the groundwork for the next round of the trade conflict.

But beneath the noise, a quieter shift went largely unnoticed. The White House confirmed a “substantially lowered Reciprocal Tariff” of 10% on all imports—a far cry from the original fire and fury. In truth, this was no reciprocal tariff; it was a general tariff introduced by stealth. If it holds, it’s not a retreat but a calculated early win for Trump in what promises to be a long, grinding economic battle.

While the 10% general tariff may appear modest next to the headline-grabbing 145% on Chinese goods, it signals a powerful shift. Trump has effectively seized tariff-setting authority from Congress, repositioning the presidency as the lead architect of trade policy. This subtle but seismic change breaks from tradition, where Congress held the power to regulate tariffs under Article I, Section 8, and passed legislation like the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930 and the Trade Act of 1974. Trump bypassed this process, invoking national security under Section 232 of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act—a rarely invoked executive lever last used for steel tariffs in 2018.

Now, with this legal foothold, Trump can adjust his general tariffs at will—10% today could rise to 20% or 40% tomorrow, reminiscent of the late-19th-century protectionist era—all without the constraints of legislative gridlock.

Historically, American protectionists insisted on broad tariffs for all, wary that negotiating one-off “deals” could open the door to lobbying influence and government favouritism. Trump’s general tariff, while nodding to that tradition, also paves the way for future hikes. So while the headlines focused on his climbdown, Trump may have quietly won something much bigger: the first victory in a renewed tariff war. Yet, the true, more brutal battle trade remains ahead.

China Strikes Back

As the U.S.-China trade war escalated, President Donald Trump quietly urged Chinese officials to have President Xi Jinping initiate tariff talks, offering a subtle diplomatic off-ramp. Beijing, however, declined. On April 11, 2025, China retaliated by raising tariffs on U.S. goods to 125%, responding boldly to Trump’s 145% levies, signalling its intent to meet economic fire with fire.

With rivalry unlikely to subside—and America showing no signs of retreating from global leadership—China has every reason to test the strength of its economic independence. Just as Russia navigated Western sanctions following its 2022 invasion of Ukraine by pivoting trade eastward, China is positioning itself to weather similar pressures. Dismissing its economy as a “paper tiger” risks repeating the West’s earlier miscalculations with turning the Russian ruble into rubble.

Trump Blinks

On Saturday, April 12, President Trump largely conceded in the tariff war, exempting smartphones, computers, and many key electronics and components, including memory cards, solar cells, and semiconductors. Reports suggest tech giants like Apple lobbied for this significant hole in Trump’s tariff wall. This move contradicts the traditional American protectionist mantra that tariffs should be broad and free from the influence of insiders and lobbyists. As of now, China has not altered its stance, continuing to impose 125% tariffs on U.S. goods.

Trump’s climbdown underscores that, in many ways, China holds the upper hand. It can redirect exports to its massive domestic market or to expanding allies within the BRICS bloc, supported by initiatives like the Belt and Road. By stimulating internal consumption—through incentives, infrastructure development, or even military retooling—China can gradually elevate living standards that have long been tied to export-driven demand. Shifting economic focus from producing consumer goods for Americans to building a blue-water navy could also help China evolve into a formidable maritime power.

The U.S., in contrast, faces more immediate fallout: cutting off Chinese goods still under tariffs—machinery, furniture, pharmaceuticals, apparel—threatens widespread shortages and rising costs, endangering decades of consumer-driven prosperity, in exchange for the ever receding promise of reindustrialization. Without ironclad general tariffs, corporations will invest in lobbying Trump for exemptions, not investing in new plant in America.

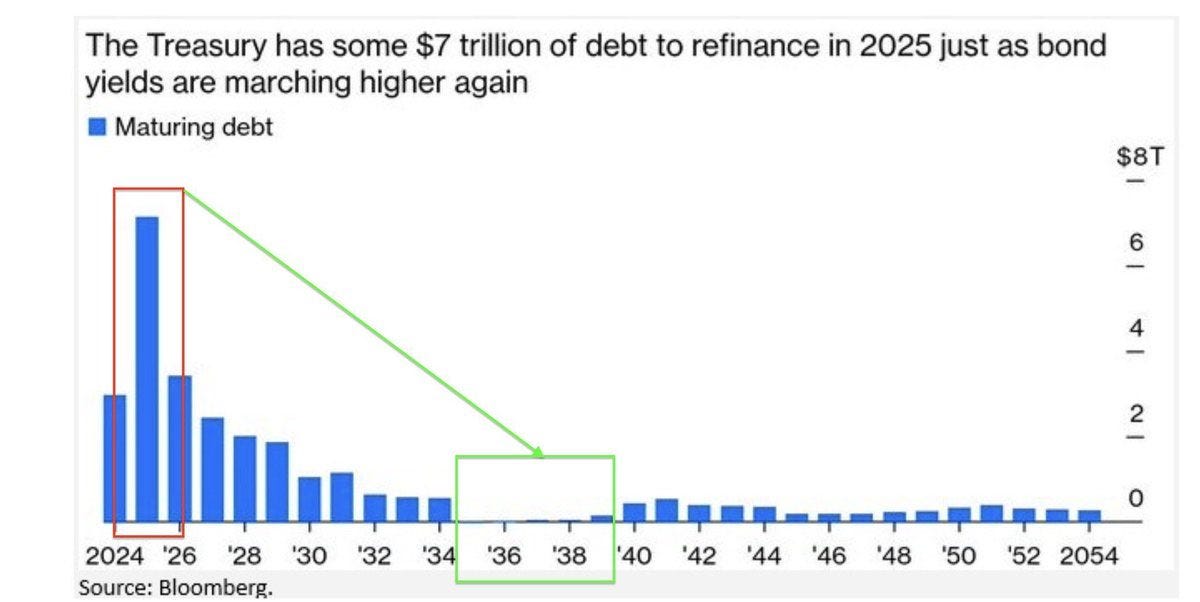

The stakes are further amplified by mounting financial pressure. With $7.6 trillion in U.S. debt maturing in 2025 and a $2 trillion deficit—even after efficiency measures—rising Treasury yields are poised to strain federal budgets. Wall Street is growing increasingly anxious, urging Trump to ease tariffs to avoid economic fallout. Yet politically, confronting China plays well with his base, framing the conflict as a bold stand against an assertive rival—unlike trade disputes with allies such as Europe, which generate more discomfort than applause.

If the tech giants managed to punch a hole in Trump’s tariff wall, it will be the iron fist of the bond market that eventually shatters it completely.

China’s 125% tariff—strategically set 20% below the U.S. rate—allows Xi to position the U.S. as the aggressor on the global stage. A planned EU-China summit in Beijing in July 2025 signals a shift in alliances, as some U.S. allies hedge their bets in response to Trump’s hardball tactics. Meanwhile, Xi sees little reason to interrupt what he perceives as a strategic misstep. Napoleon’s old adage rings true: “Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake.” By stress-testing its economy now, China is preparing for the long game—one it hopes will culminate in its ascension to the top of the global order.

Dollar Dominance

The paradox is striking: a global move toward de-dollarization is not just inevitable, it is essential for America's reindustrialization. The very "mighty dollar" that has long fuelled global dominance is also the root of America's trade deficits and its growing inability to compete in global manufacturing. Trump can choose the dollar or he can begin the hard road to reindustrialization, but he cannot have both.

Nations historically bank trade surpluses to amass geopolitical power—Britain in the 19th century, the U.S. in the 20th, and now China in the 21st. But trade deficits over time weaken a nation, and America’s geopolitical retreat in the 21st century is a case in point. Soon, Ukraine will likely fall, more or less, to Russia.

The axis of China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, and their BRICS allies is steadily gaining strength, accruing geopolitical weight within the very system they once aimed to resist. As Antonio Gramsci observed, "The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum, a great variety of morbid symptoms appear." We are now standing on the edge of such an interregnum.

At the heart of the conflict lies a contradiction: the United States still shoulders the dual mantle of global military enforcer and financial hegemon. But the internal strains of this dual role—both political and economic—are increasingly unsustainable. Meanwhile, the China/BRICS bloc is not yet prepared—or perhaps not yet willing—to assume these global responsibilities.

Note: In my next article, I will explore in greater detail why it is impossible for the U.S. to run budget surpluses while the dollar remains the world’s reserve currency.

Always very educating to read your articles. I enjoyed the perspective of global wars (I know it’s not the first time you wrote about it but this time you elaborated more).

Looking forward to your next article on GRC vs budget surplus.

In the meantime, what makes you think China is not yet prepared or unwilling to lead?