Clash of Hemispheres

Sundered are the peacemakers: Trump and Putin speak across a neurological fault line, where the left and right hemispheres wage their dissonant struggle over time, history, and truth.

By the forest’s edge, a figure stoops to a bone—grasping, parsing, labouring with care. The world is near, close enough to hold, to prise apart, to study in its grain; each detail a truth, each fragment a feast.

Yet this very act of consumption holds a dark reciprocity. The bone it savours was once the limb of another—a creature that, in its own narrow vigilance, saw only the beetle beneath the root, the glint of pattern on a leaf, the small, certain world before its nose. So fixed upon the details, the prey missed the pause in the wind, the silence of the birds, the heavier footfall drawing near.

In turn, the figure eats—but also pauses. Unconsciously a portion of its brain keeps watch; the forest gathers around it like a breath held , a form of prayer. Its awareness loosens from the half-consumed creature to the foreboding thicket at its flank. It prays, not for prey, but for pattern; not for movement, but for meaning—seeking, in that widening stillness, not to become prey itself.

In this double movement—to feast and to avoid becoming feast—are lodged the oldest divisions of mind: the capacity to grasp the particular and the need to sense the whole. Even our language remembers the split: prey and pray, twin syllables sitting cheek by jowl in the human ear, whispering that to live is to attend in two directions at once—to the bone in its immediacy, and to the horizon with a question—an anxious inquiry into what the waiting forest holds in store.

Our minds still bear the imprint of this ancient bifurcation, a lineage from the first animals who had to reconcile two modes of knowing: one that narrows, fixes, and makes the world graspable; another that widens, listens, and feels for its living coherence. Between the two runs the oldest tension in consciousness itself—the need to act, and the need to understand what one’s action belongs to.

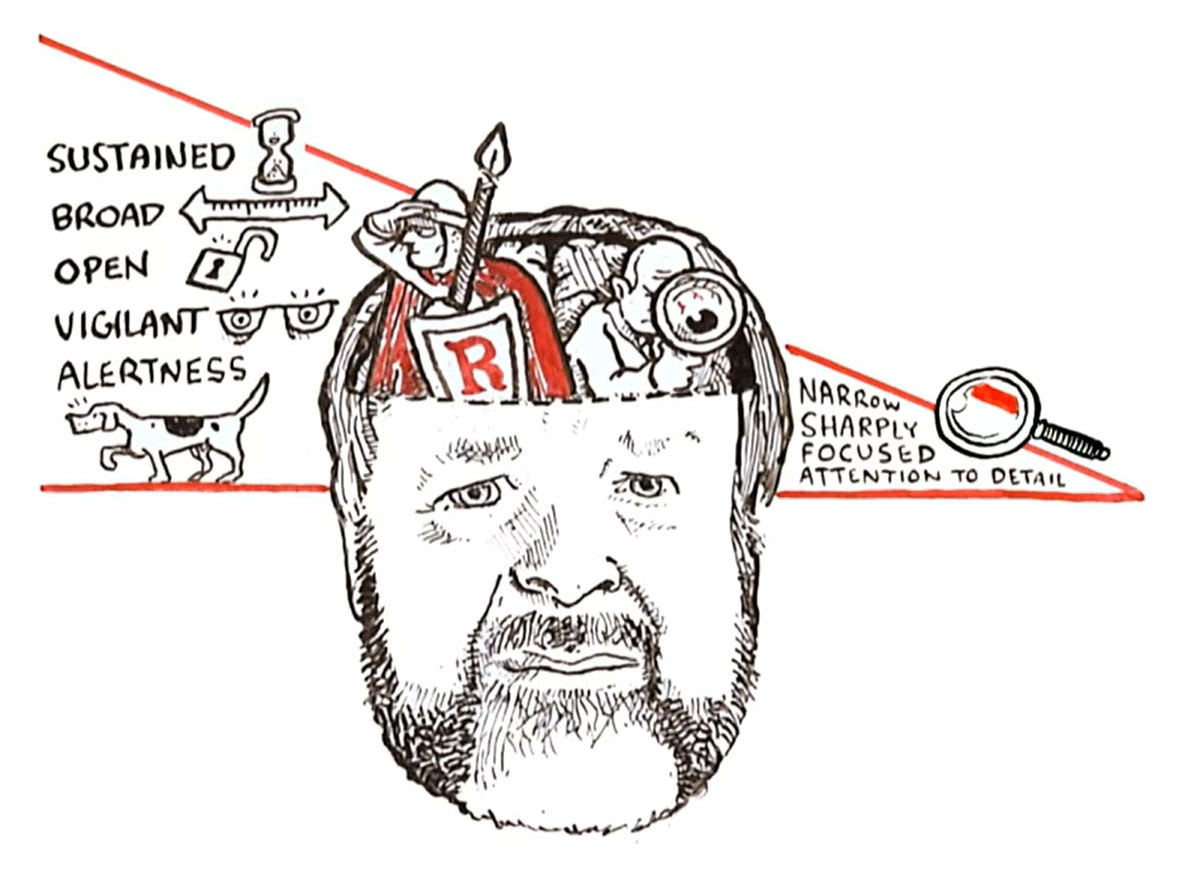

The philosopher and neurologist Iain McGilchrist—a thinker who moves between the metaphysical vastness of the humanities and the clinical precision of neuroscience—names these two modes of being the left and right hemispheres. What he describes is not a simple anatomical division, but a living clash of hemispheres: rival forms of attention that coexist, contend, and together shape the world we know.

They are like the sniper and his spotter. The left hemisphere (LH) presses its eye to the scope, isolating the target with lethal clarity; the right hemisphere (RH) sweeps the horizon, reading the wind, the light, and the meaning of the terrain. It is the difference between the emissary who executes and the master who understands, between tactical manoeuvre and strategic vision—each dependent on the other, yet unequally aware of the whole.

McGilchrist’s authority lies in his command of both domains. He moves fluently through the right hemisphere’s world—the realm of metaphor, context, and embodied continuity, long home to poetry, religion, and art—and with equal rigor through the left hemisphere’s world of data, definition, and discrete measurement, the bedrock of modern science. His warning is not moral but structural: the sniper must remain guided by the spotter. Yet our civilization has allowed the emissary to usurp the master, mistaking the bright clarity of his scope for the full field of truth. We have enthroned mechanism over organism, the model over the reality, precision over perspective—a triumph of the LH that risks making us prey to the contexts we have learned to ignore.

The Neural Counterweight: A System in Balance

To appreciate the high stakes of this cognitive divide, it is essential to move beyond a simplistic caricature. This is not a story of a logical left hemisphere versus an emotional right—a dated notion that belongs in the same basket of errors as the one which held margarine to be healthier than butter.

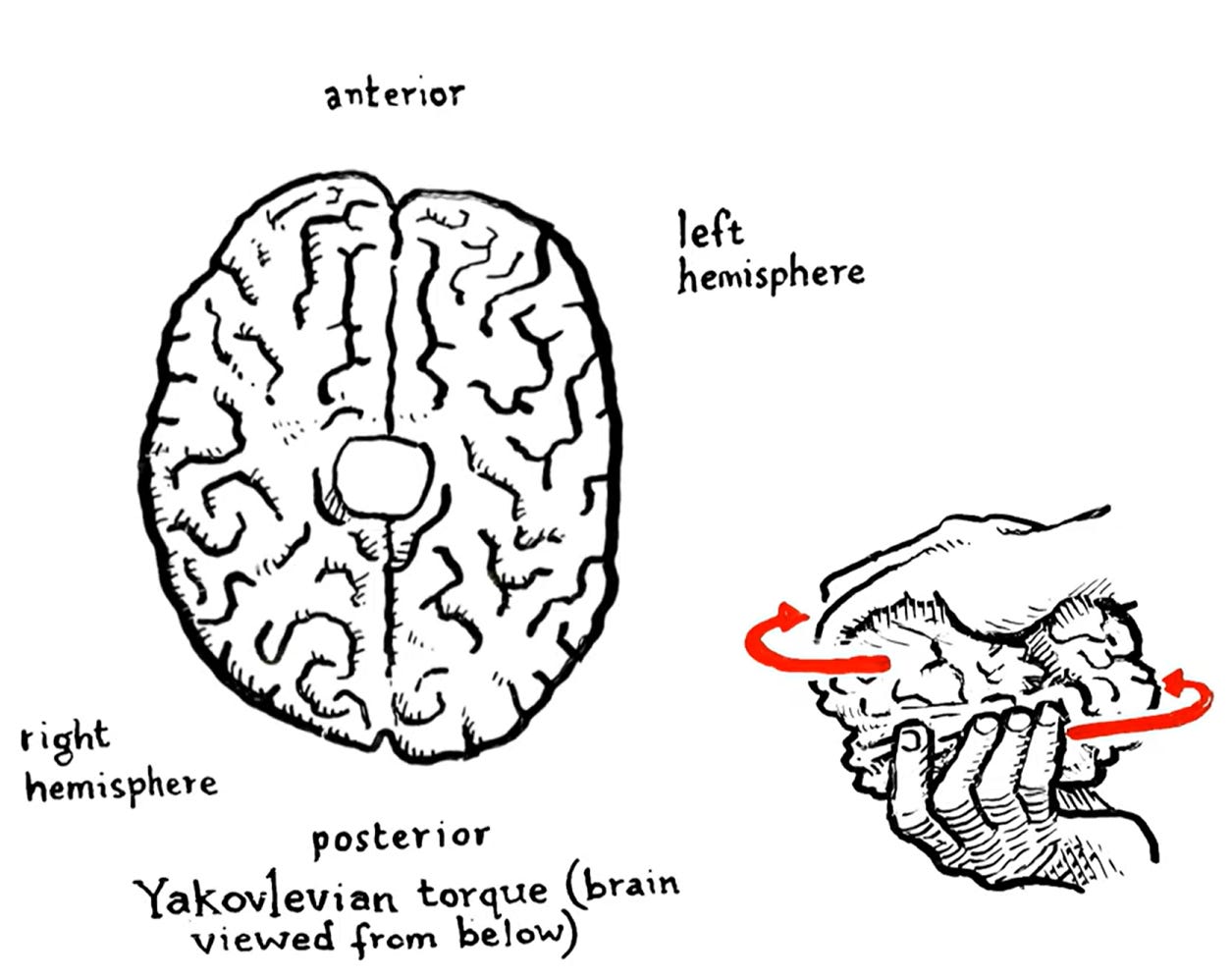

Instead, McGilchrist presents a more profound and subtle architecture: the brain is an organ of connection, yet it is also profoundly divided. Evidence from split-brain patients reveals two autonomous, parallel streams of consciousness. Intriguingly, this divide is deepening in our evolutionary history; the ratio of brain mass to the corpus callosum—the thick bundle of neural fibres that connects the hemispheres—is getting smaller. Far from being a simple bridge, one of its primary functions is to inhibit the other hemisphere, allowing for specialized, undisturbed processing. It is less a corridor of cooperation and more of a neural firewall.

This functional divide is etched into the brain’s very anatomy. The human skull may be symmetrical, but the brain is not. It is as if the whole structure has been given a sharp, clockwise twist: the right hemisphere is broader in the frontal lobe, the seat of contextual understanding, while the left is broader in the occipital lobe. This physical asymmetry reflects a deep functional one.

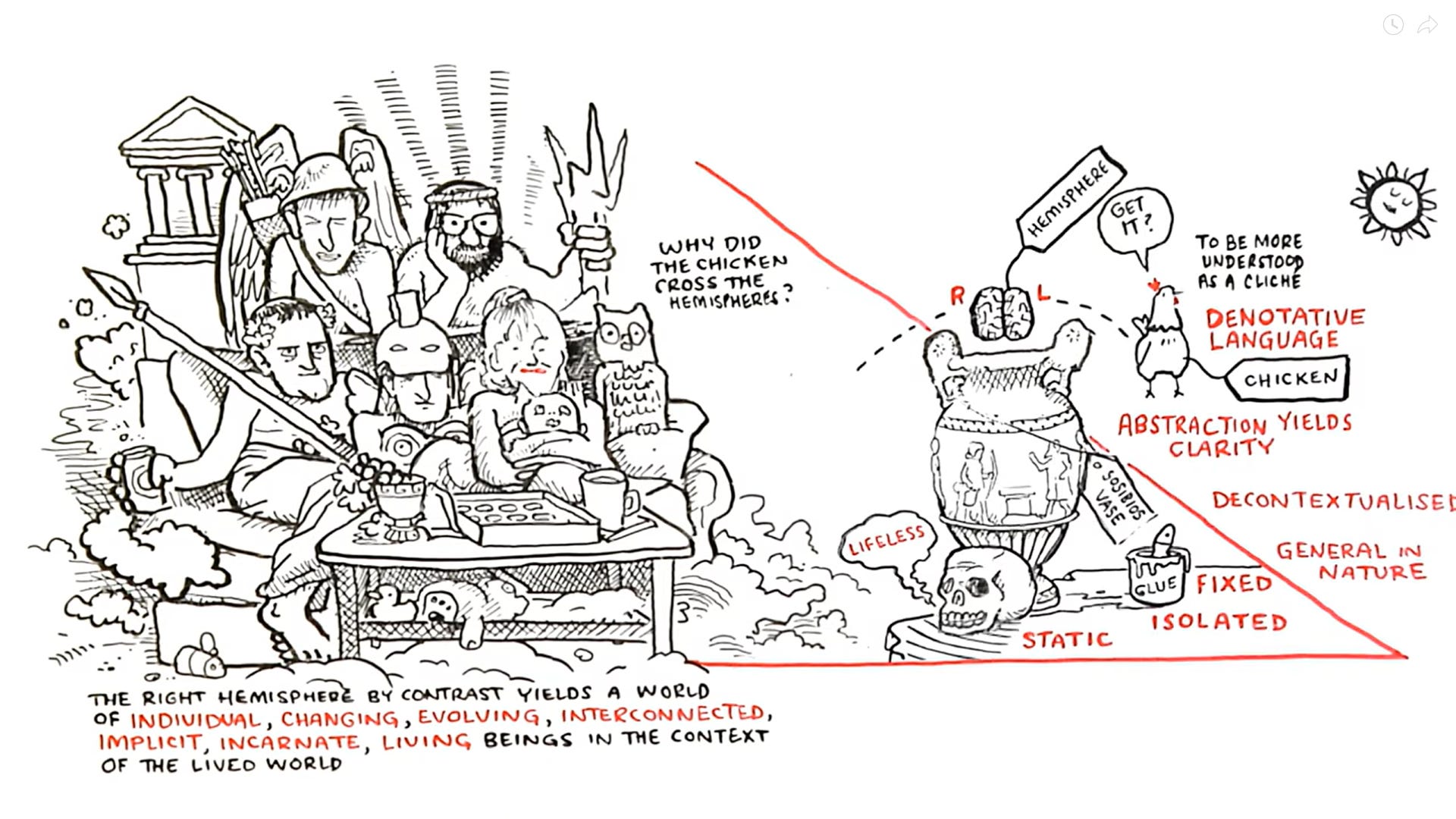

The LH’s gift is its narrowly focused attention, akin to a bird pecking food from specific pebbles on a beach. It is optimized to manipulate the world, and to do so, it requires a simplified, utilitarian version of reality—a cognitive map that “works,” even if it is not the territory itself. It operates within a closed, self-consistent system that can achieve a sterile perfection, but at the price of emptiness.

The RH, in contrast, is broadly vigilant, constantly scanning not just the pebbles but the entire beach, the sky, and the horizon for the shadow of a hawk. It is the source of our embodied engagement with a complex, flowing world. It understands individuals, not just categories; it grasps implicit meanings and metaphor. It is, in a sense, the brain’s built-in “devil’s advocate,” seeing everything in its context and challenging the left’s certainties.

The key to a healthy mind—and by extension, a healthy culture—is not choosing one over the other, but achieving a dynamic balance under the rightful guidance of the right hemisphere. We need the LH to manipulate the world, but we need the RH to understand the context well enough to manipulate it effectively. This is the neurobiological foundation of strategic empathy.

Our frontal lobes provide the crucial pause, the distance from the immediate present. This distance is the regulator of this balance. Stand too close to the world, and you simply “bite”—a reactive, LH-loaded state of literalness and impulse. Stand too far back, and you risk the ivory tower—an RH-loaded state of abstract theorizing untethered from practical reality, your head in the clouds. But find the right distance, and the same cognitive space enables both Machiavellian calculation and profound compassion. The ultimate wisdom lies in recognizing that the sniper must always take his cue from the spotter, for the spotter alone sees the true context of the shot.

The Cultural Cortex: East, West, and the Russian Liminal

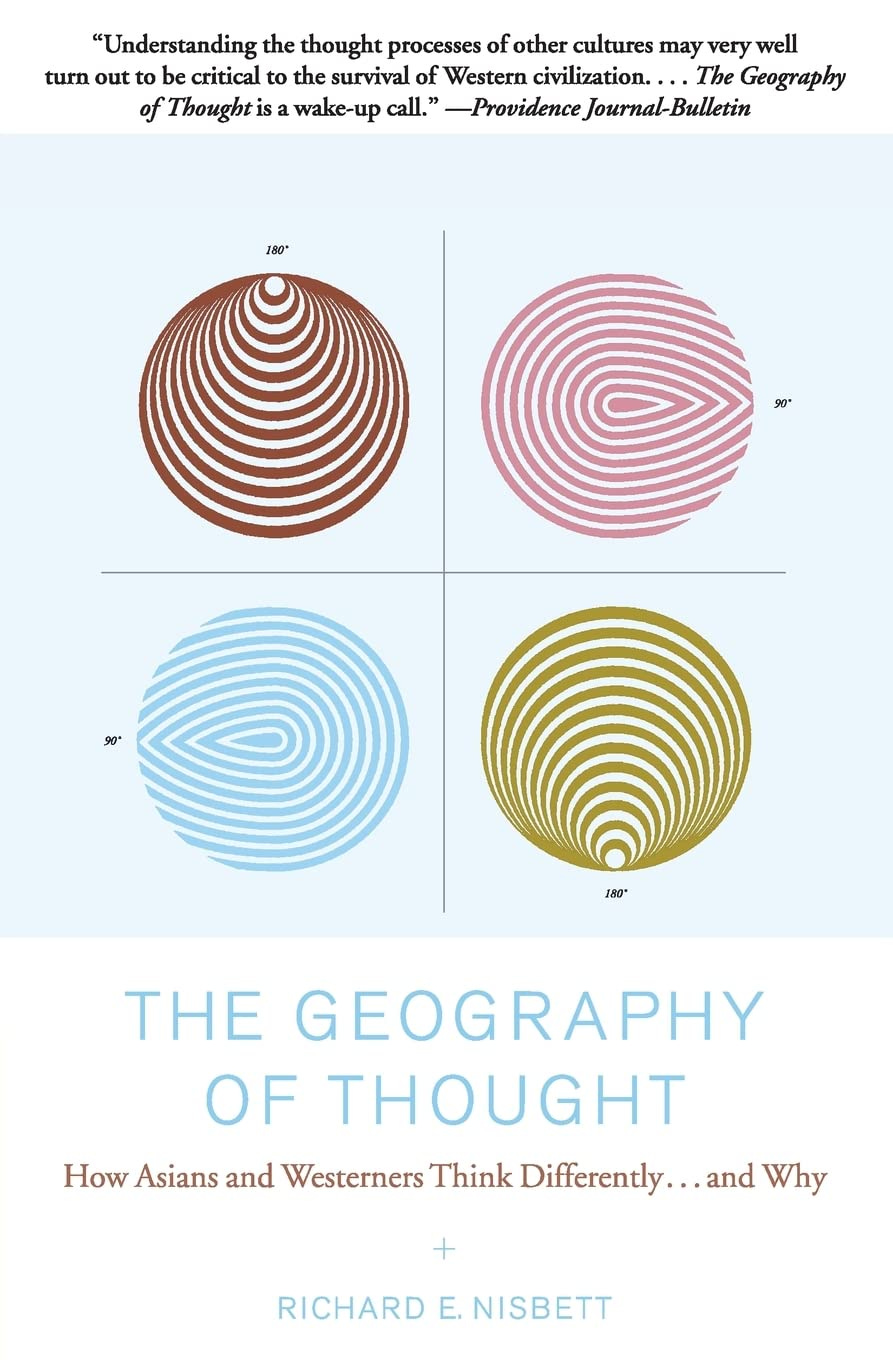

This neurological hemispheric clash finds a powerful and corroborating echo in the realm of social psychology. While McGilchrist’s primary focus is the Western trajectory, his framework is strikingly illuminated by the work of Richard E. Nisbett in his landmark study, The Geography of Thought. Through decades of empirical work, Nisbett identifies a profound cultural divergence: Eastern Asian societies, shaped by interdependent, agricultural, and Confucian traditions, tend toward holistic thought—perceiving the entire field, valuing context, and accepting contradiction. The Western mind, descended from the individualist, mercantile, and disputatious Greek city-states, leans toward analytic thought—focusing on central objects, categorizing with linear logic, and applying abstract rules.

Though McGilchrist and Nisbett operate from different disciplines, their maps of the mind are strikingly convergent. The holistic thinker, with their attention to the entire field and its relationships, operates in a mode aligned with the right hemisphere’s wide, contextual awareness. The analytic thinker, focusing on decontextualized objects and linear causality, mirrors the left hemisphere’s narrowing, utility-driven focus. It is crucial to stress that this is a matter of cultural emphasis and degree, not a rigid, absolute divide. No society is purely one or the other; rather, cultures cultivate and privilege different balances of these innate human capacities. McGilchrist himself theorizes a civilizational rhythm where nascent cultures lean RH-heavy, but as they consolidate success, the LH inevitably usurps control—often presaging a period of rigidity and decline.

This cultural lens reveals Russia as the world’s quintessential liminal case. Straddling the continents and the cognitive traditions, it has perpetually digested both the holistic, context-laden worldview of the East and the analytic, universalizing impulses of the West. Its history is a long, turbulent negotiation between these two orientations. And in a modern world dominated by a West in thrall to a left-hemisphere worldview, Russia’s own identity has been pushed, in reaction, toward its right-hemispheric pole.

To understand the sputtering diplomatic encounters between a Russian President like Vladimir Putin and a Western leader like Donald Trump is to witness this cognitive liminality crashing against a Western analytic frame. It is precisely at this volatile juncture—where Russia’s deep, contextual time, hardened in reaction, meets the West’s demand for immediate, transactional solutions—that the stage was set for the Alaska summit.

Anchors Away in Anchorage

The Alaska summit between the U.S. and Russia can be read as a clash of hemispheres, both cognitive and temporal. President Putin operates with a distinctly right-hemisphere lens: he situates the war in Ukraine not as a momentary border dispute but as a chapter in a millennium-long narrative. In interviews and speeches, he traces a historical line from the 9th-century founding of Kyivan Rus, through the Mongol invasions, Catherine the Great, and the Soviet period, framing the modern Ukrainian state as a historical anomaly. The present conflict is not an isolated event but a disruption in a long civilizational arc.

This temporal depth was concretized in his June 14, 2024, speech—what can be called Istanbul Plus. The “Istanbul” refers to the tentative agreements reached in 2022, which provided a baseline: Ukrainian neutrality and interim security arrangements. The “Plus” is Putin’s subsequent escalation—the formal annexation of four regions and the hardening of terms into non-negotiable realities. His demands—Ukrainian withdrawal from Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson; neutral status; demilitarization; and recognition of Crimea and the new territories as Russian—functioned as a hard anchor, rooted in a coherent historical narrative. The right hemisphere thrives on such temporal and contextual continuity: the anchor is stable, rationalized, and capable of withstanding short-term disruptions.

In contrast, the U.S. approach, particularly under Trump, reflected the left hemisphere’s temporal orientation: compressed, immediate, and transactional. Left-hemisphere thinking seeks resolution in the present, measuring success by rapid, concrete outcomes rather than coherence over time. The West’s task is made more difficult by the fact that its own hard anchor—the strategic defeat of Russia and the restoration of Ukraine’s 1991 borders—is no longer achievable, if it ever was. The best the West can now hope for is a frozen conflict along the current front lines, an outcome that would see roughly 80 percent of Ukraine melt into the NATO fold—not a negligible success by any means.

But to reach even a frozen conflict, Putin’s anchor had to be dislodged. The deployment of Steve Witkoff to Moscow was the left hemisphere’s masterstroke: a tactical, improvisational gambit aimed at reframing the entire engagement. The proposal he carried was a classic re-anchoring manoeuvre. It reportedly required only a Ukrainian withdrawal from the Donbas, seemingly leaving portions of Zaporizhzhia and Kherson under Ukrainian control—seen as a significant retreat from Putin’s “maximalist” demands. Astoundingly, Putin initially accepted this as a new basis for talks. For a fleeting moment, Trump’s left-hemisphere ingenuity had succeeded: present-tense pragmatism had opened a crack in the wall of historical continuity.

Yet at the Alaska summit, the manoeuvre unravelled. When Putin sought confirmation, Trump hesitated, deferred to allies, and then performed a devastating pivot: he recast the Witkoff proposal as Russia’s position, transforming a potential shared baseline into a unilateral ceiling. The negotiations were suddenly cast into an anchorless void. This incoherence culminated weeks later when Trump first announced, then abruptly cancelled, a Budapest summit, blaming Moscow’s return to “maximalist” demands. In this sequence, the fatal limit of the left-hemisphere mode was laid bare: its brilliance in destabilizing the old is unmatched, but its capacity to build and sustain a new reality is brittle. It can pull up an anchor but cannot set a new, durable one.

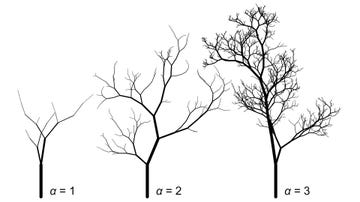

Meanwhile, Putin’s right-hemisphere cognition is engineered to endure such turbulence. Deprived of his previous anchor by Witkoff, Putin can simply re-anchor the discussion in his own deep time. He can revert to Istanbul Plus or advance to an Istanbul Plus Plus, now invoking the open-ended historical concept of Novorossiya—a move that requires no listing of specific oblasts but implies an endless frontier. The structure is fundamentally fractal: the core demands for neutrality, demilitarization, and territorial acquisition are repeated and enlarged, replicating the same strategic shape at different scales. Like the branching of a tree, the form renews itself while remaining recognizably whole. This recursive self-similarity is the genius of right-hemisphere cognition, which perceives—and weaves—coherence through the chaos of change.

The left hemisphere, by contrast, demands closure—an endpoint, a result, a frozen snapshot. But the right sees time and history as living forms, ramifying like rivers, growing in asymmetry yet retaining order. It is not a linear progress toward resolution but an unfolding of meaning that deepens with each return.

In this light, the fraught dialogue between Washington and Moscow itself functions as a kind of geopolitical corpus callosum—a necessary, if flawed, connection between two irreconcilable cognitive worlds. Its purpose is not to create harmony, but to manage the tension, to transmit signals of threat and opportunity across the divide, and to inhibit one side from fully overwhelming the other. That the talks in Alaska occurred at all is a testament to this imperative. That they failed so spectacularly reveals the weakness of the connection.

In the end, the right hemisphere abhors the very drift the left hemisphere creates; it seeks a coherence across time that the left, in its pursuit of a conclusive present, is blind to. This is the perennial tension—not just of the Alaska summit, but of the mind itself: the need to act and the need to belong to a story that outlasts the action. It is the ultimate lesson of the forest: to see only the immediate target or tree is to miss the pattern of the whole, and to risk, in the final reckoning, becoming a feast for a timeline you never learned to see.

Well woven neuro-cultural analytical overview that knits the paradox nicely, whilst minimising the contradictions…thank you…it’s a dance with the devil & the damsel, in themselves spawned by the marriage of Jekyl & Hyde lurking in the shadows, anima wrestling with animus, lurching along the cliff of disaster in the un-aligned ongoing pursuit of a perfect world soul…which archetype will each persona manifest in its collective course of individuation…??…Gaia weeps in anguish, whilst Sol sighs in resignation…where will this errant human evolution flow next…!?

So well written, one of your best pieces (next to the world island and GRC articles).