Arctic Encirclement

Geopolitical thunder on the tundra: As the noose tightens on the battlefield, a proxy may be sacrificed—Ukraine’s fate hangs in the balance between Trump’s brinkmanship and Putin’s relentless advance.

Along the Ukraine war’s front lines, Russian advances have shed their glacial pace. As Ukraine builds strong defensive structures in the Donbass, their lack of manpower means these fortification lines are quickly seized by Russian sabotage and reconnaissance groups, and once entrenched, Ukraine has no ability to dislodge them. As so often in war, the rampart erected for safety becomes, in the turn of a tide, the enemy’s throne.

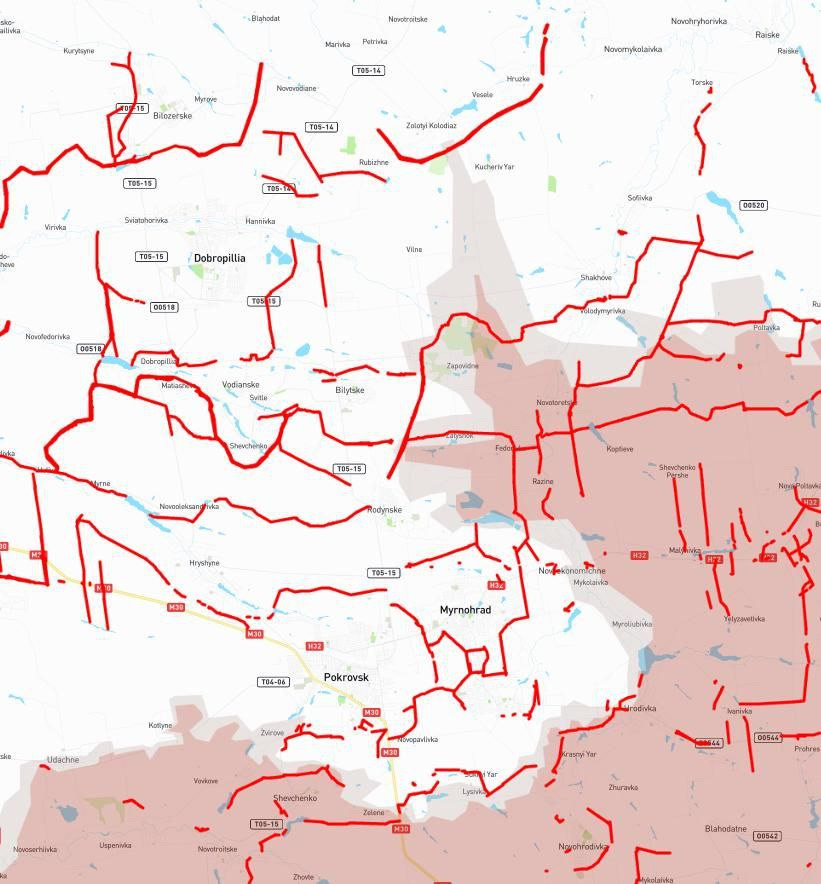

After nearly a year of attritional pressure, Chasov Yar was finally prised away, becoming the pivot for a broader operational design: four emerging kotyols—cauldrons—taking shape around Kupyansk, Seversk, Konstantinovka, and the logistics hub of Pokrovsk. Each is being sealed not through frontal assaults, but by the patient tightening of artillery arcs and the interdiction of supply routes—a calculated geometry of collapse drawn in deliberate strokes.

A kotyol—literally “boiler” in Russian military usage, often rendered in English as “cauldron”—carries the image of a kettle under heat: pressure mounting, steam building, escape possible only through the spout. On the battlefield, that “spout” may be slammed shut in Clausewitzian fashion, as at Stalingrad—an enemy fixed, surrounded, annihilated. Or it may be left ajar, creating a “semi-cauldron” in which a narrow corridor tempts the trapped into pre-sighted killing grounds. This is Sun Tzu’s counsel to leave an enemy an outlet—not from clemency, but to erode the desperation that fuels last stands. The illusion of escape breaks cohesion; retreat becomes rout.

At Korsun–Shevchenkovsky in February 1944, German forces west of the Dnieper were encircled but left a single corridor through frozen fields. Soviet artillery and aircraft turned that corridor into a slaughterhouse, annihilating men and materiel as they fled.

In the early phase of the Ukraine war, two brutal battles in the Donbas region—Ilovaisk in 2014 and Debaltseve in 2015—recreated the open-sided trap: the fiercest losses did not occur within the encirclement itself, but during the desperate flight through its narrow exit. These engagements were more than just military defeats; each semi-cauldron emptied directly into negotiation rooms in Minsk where Moscow leveraged battlefield gains for diplomatic concessions. The front’s geometry dictated the pace of diplomacy—the tighter the encirclement, the louder the calls for “peace.”

The Minsk accords, brokered under German and French mediation, were nothing more than holding patterns from the outset—designed less to settle than to forestall collapse while Ukraine avoided concessions and rebuilt itself as a NATO proxy.

Minsk I, signed in September 2014 after the rout at Ilovaisk, promised ceasefires, prisoner exchanges, and autonomy for the Donbas. Kiev treated it as a breathing spell; hostilities resumed within weeks.

Minsk II was born of Debaltseve’s encirclement in February 2015. Ukrainian forces in the strategic rail hub, under relentless artillery fire, petitioned for withdrawal. As casualty reports mounted, Merkel abandoned her studied detachment, flying to Moscow to plead for a halt. The accord signed days later froze the front just long enough to extract what remained of Ukraine’s garrison. It was less a peace than an act of triage—a political tourniquet disguising a military defeat. Merkel’s dash to the Kremlin revealed the West’s real posture: when Russia advanced decisively, “peace” meant damage control.

Minsk II came with the imprimatur of UN Security Council Resolution 2202, prescribing special status for the Donbas—amnesty, local elections, language rights—before Ukraine regained control of the border. In private, Western leaders knew Kiev would never comply. Their candour surfaced years later: in December 2022, Merkel admitted Minsk had been a device to “give Ukraine time,” while Hollande confirmed it was used “to strengthen its army.” Seven years of Western training, ideological radicalization, and encrypted communications followed. By the eve of the 2022 invasion, Russia’s local advantages had been eroded. The ceasefires had done their work: NATO’s proxy was ready.

As pressure builds in the four cauldrons today, are we on the brink of a Minsk III in Alaska?

Trump Slips a Neocon Cauldron?

If the kotyol is a battlefield trap, its political analogue is no less constricting. The man circling inside it today is not a Ukrainian general but the president of the United States. Six months into his second term, Donald Trump harbours no illusions about Ukraine’s battlefield trajectory. The war’s end is not in doubt: Kiev is losing, and much of the Western hardware that reaches the front is destroyed by Russian strikes or wasted in doomed offensives. For Trump, Ukraine is a distraction from his real priorities. Israel’s air-defense stockpiles are running down; U.S. arsenals must be conserved for the possibility of confrontation with China. The sooner the war ends, the better—and the terms matter little to him.

Others in Washington see profit in prolongation. Neoconservatives and their Republican auxiliaries, led by Lindsey Graham, are trying to lock Trump into a “political cauldron” of their own design: by forcing him to issue secondary tariffs on buyers of Russian oil. These would spike global energy prices, feed inflation, and erode Trump’s economic standing—costs his intraparty rivals would gladly pay. Trump answers with his familiar mixture of threat and hesitation, announcing sanctions or tariffs but often stopping short, and when he does act, he soon chickens out.

Hemmed in by a ring of Neocon pressure yet holding no real leverage over Russian President Putin, Trump in mid-July donned his familiar tough-man mask. He issued a theatrical “50-day ultimatum” for Russia to end the war—“or else.” The bluff was obvious. Moscow answered with silence. After two weeks of studied indifference by Putin, Trump halved the deadline to ten days, naming August 9th as “T-Day,” when “bone-crunching” sanctions would fall. The calendar advanced, the war ground on, and Russia not only ignored the threats but unveiled its first Oreshnik missile batteries—already rolling off the production line.

Trump’s attempts to pressure India and Brazil—two of the most pro-Western members of BRICS—ended in open defiance. Tariffs on Indian imports were justified as punishment for its purchase of Russian crude, often refined and resold to Europe. In reality, the measures were riddled with carve-outs, including one allowing Indian sales of Russian oil to the United States itself. Only India’s gem industry really felt the pinch.

Washington tried to turn the dispute into leverage over India’s agricultural market, demanding lower tariffs and entry for U.S. food exports. For India’s hundreds of millions of small farmers, such competition would be ruinous—echoing the collapse of Mexican agriculture under NAFTA, when peasants displaced by cheap Big Ag products, crossed into the United States in the millions. For Trump’s Big Tech backers, the result would be a boon: a new desperately poor migrant labour pool ready to be shipped to America’s gates.

Narendra Modi responded with calculated provocation. He invited Vladimir Putin to New Delhi, confirmed his attendance at a Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit in China—his first visit there in seven years—and publicly denounced the tariffs. In geopolitics, the aim is to split adversaries; Trump has managed the reverse. “Divide and rule” has become “unite and lose.”

The trade war has now bled into the strategic sphere. China has begun restricting exports of rare earth elements, the essential inputs of advanced weapons systems. A century ago, communists promised to sell capitalists the rope with which to hang themselves; today, communist China will not sell them the very metals that could be forged into weapons against it.

Nor is this Trump’s first recoil. Several times he has sought to cut Ukraine off entirely, only to back down under combined pressure from Europe and Washington’s hawks. Each time, the Neocon cauldron has tightened another notch.

Diplomatic Thunder on the Tundra

But in the blink of an eye, Trump flipped from hunted to hunter. First, he feigned victory, claiming the Kremlin had “begged” for talks to stem the tide of his tariff threats. In reality, it was his personal fixer, real estate magnate Steve Witkoff, who flew to Moscow to beg for a summit—and the Kremlin eventually granted it. On August 15th, in Anchorage, Trump will sit down with Putin.

Suddenly, Ukraine, Europe, and American hawks shifted from anticipating bone-crushing sanctions across the globe to fearing Trump will force Ukraine to surrender land and withdraw from key eastern oblasts. With one deft move, Trump slipped free from the Neocon cauldron, pivoting from besieged to initiator—for the time being.

Vice President Vance has already signalled to European leaders that they will be expected to endorse any deal that comes out of Alaska. Europe is attempting to draw the line at allowing Russia to maintain de facto control over the Ukrainian land they actually occupy. But with Ukrainian resistance collapsing, why would Russia stop today? Moscow are already calculating the potential land they will amass in say the next six months.

For Europe and the hawks, as in 2014 and 2015, today’s imperative for a ceasefire in Ukraine is less about securing peace than avoiding humiliation. The danger is that a Ukrainian withdrawal decided at the negotiating table will signify a military defeat too loudly for their Mighty Wurlitzers of propaganda to drown it out. A frozen front offers a narrative shield: not a loss, but a pause; not failure, but a “platform for further negotiations.”

In the end Europe will swallow whatever they are told to, for fear that their tariffs will be spiked. They all know that Trump’s tariff bluster targets America’s own allies more than its adversaries. Without firm American and European backing, Ukraine’s military effort risks slipping into palliative care, with a “Do Not Resuscitate” order ominously pinned to its bedside. But considering the the peace process on the Iranian nuclear issue was used to cover a surprise attack on Tehran, can the Russians really trust Trump?

Terms of Encirclement

NATO’s ideal Ukrainian intermission would lock the front along the current line of contact, leaving roughly 80% of Ukraine under Kiev’s control and Russia with the 20% it now holds. While in public the West may complain, in private this would be a stunning victory—Ukraine, bloodied but sovereign over most of its territory, with NATO arms and advisers flowing in to rebuild and rearm. NATO missile installations could be built in Kharkov, less than 700 kilometres from Moscow. Crimea and the Black Sea coast could wait for retrieval in the 2030s or 2040s, once time, training, and matériel had shifted the balance.

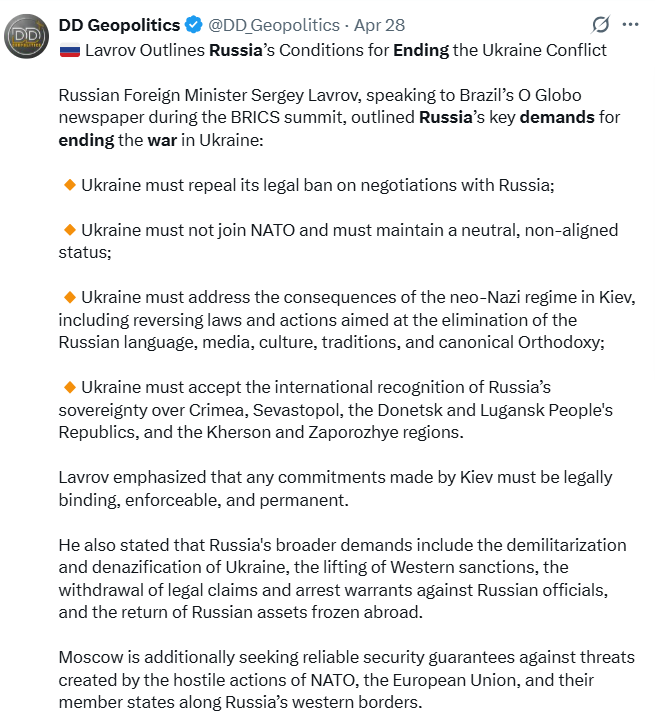

The Kremlin’s preferred ending is different in kind. What it seeks is not the cartographic freezing of a divided Ukraine but the submission of the whole—withdrawal from the four oblasts it claims, and binding assurances of perpetual NATO abstention. The model is not South Korea’s militarised stalemate, but Belarus’s docile alignment: a Ukraine with the form of sovereignty but none of its strategic substance.

For Zelensky, the constitutional bar on territorial concessions is a useful wartime flourish. But constitutions make poor shields against military realities imposed by force and ratified by exhaustion. If, after the Alaska summit, Trump instructs him to withdraw from specified regions, his generals do have the legal power to obey; the evacuation will hand Moscow de facto control, leaving the formalities—the de jure recognition of sovereignty—to be dressed up later in referenda.

Russian guns will fall silent once such withdrawals are announced, it would not make great optics for Russia to fire on retreating troops, despite the West not seeming to have a problem with starving civilians getting shot up in Gaza. But Putin would need to pre-empt an 80–20 NATO “victory” by warning that any post-ceasefire influx of Western arms or “volunteer” contingents—especially to Odessa—remains a legitimate target. Negotiations would then follow Ukraine’s pullback, by which point Kiev’s bargaining power will have ebbed still further, their political cohesion will be tested by the risk of nationalist militias rejecting retreat from “sacred” Ukrainian soil.

Russia’s maximal aims remain fixed: Ukrainian withdrawal from Kherson and Zaporizhzhia; codified neutrality; demilitarisation; and the pliable yet potent label of “denazification.” With Ukraine’s forces stranded behind shattered Donbass lines, Moscow holds the upper hand. In Brussels and London, outrage is strangely muted—as if Europe’s polished diplomats have already penned Zelensky’s fate in a ledger of sacrifice. Their temperance is a cold Judas kiss upon Kiev’s brow, while Trump compulsively scrubs at the blood of Ukraine from his hands—an echo of Lady Macbeth’s tortured guilt—treating the war as a stain he desperately wishes to erase, yet cannot escape.

American hawks, steeped in a reflexive animus toward all things Russian, will not slip quietly into irrelevance. In Washington, Neoconservatives may gamble on sabotage at home—engineering scandal, launching kompromat offensives, even dredging up lurid, Epstein-adjacent rumours—to weaken Trump’s hand before any deal can be struck.

If the summit fails and Putin holds fast—no NATO personnel in Ukraine, no foreign arms—the worst-case scenario for Russia would be roughly six months of continued Russian advance against an already demoralised Ukraine, before a total collapse. But if he hesitates and agrees to a premature ceasefire—and releases Ukrainians trapped in the Donbass cauldrons—NATO could seize the opening, lock in its share of the country, and call it “strategic containment” of Russia. In this duel of closures and encirclements, the margin for error is slender, and the price of miscalculation—total.

If Putin falls for a “Minsk III” trap, his continued rule in Russia will be in peril. Three “Minsks” and you are out.

Putin’s Alaska Summit: Shattering the Moral Chiaroscuro

The West’s information war thrives on moral chiaroscuro—a Renaissance conceit where light and dark clash in stark, unblended contrasts. In this propaganda palette, Zelensky is rendered in saintly whites, Putin in demonic blacks, a cartoonish duality that tidies away the messy greys of geopolitics.

Why would Putin risk a Minsk III deal with an America that is notoriously agreement incapable? By stepping onto American soil for the Alaska summit, Putin gains something subtler: the chance to swap this crude binary for moral pointillism, in which scattered dots of ambiguity erode the West’s rigid moral canvas. A handshake with Trump, the grey neutrality of the Alaskan backdrop, the optics of negotiation rather than isolation—each becomes a pixel in a more complicated portrait, one that blurs the edges of villainy and nudges the silhouette toward something recognisably human.

In Latin America there’s a word—malinchismo—for the fascination with the outsider, the reflexive privileging of the foreigner’s esteem. Some in Russia accuse Putin of a similar weakness, an overinvestment in how he is received in Western capitals. They see this as the flaw that led to the first two Minsk accords, where a lightweight like François Hollande walked away with the better hand.

The alternative reading is colder: in 2014, Putin simply lacked the economic insulation he now enjoys. Russia was then far more vulnerable to sanctions; today, with parallel trade routes and energy leverage in place, he can afford the luxury of a drawn-out game.

In either case, the Alaska summit offers rewards beyond the battlefield. It’s a chance to signal—to domestic elites and to a watching world—that Putin is not a pariah but a peer. It allows him to test Trump’s resolve in person and to deepen the fracture lines within the West. And, like a general loosening the lid on a kotyol just enough to let the pressure vent in the direction he chooses, Putin may see Alaska as a venue where US-Russian diplomatic steam can be released on his terms.

As always, Kevin enriches our understanding of geopolitical knots.

I am most attracted to a geopolitical understanding that America and Russia reach certain understandings:

1. Iran to rejoin the West due to its geopolitical and economic (easily a $1 billion-plus economy) heft;

2. Ukraine to become a Finlandanized nation (for the younger folks, Finlandization meant a western-oriented economy but with no political-defense ties to the West.

Russia has been wanting to stop US expansion and threats on its border via negotiations/ diplomacy for over a decade. US refused so russia used force. US now wanting negotiations and diplomacy is a clear sign that russia has won. It's forced the US to the table.

I find it hard to believe that the US will accept russian demands, so imo the conflict will be settled on the battlefield. Ukraine will be completely defeated and a pro russian government installed in Kiev.

US will continue agitation via both its standard covert methods and via its European proxies and others in the Caucasus etc.