Trump’s American Rebuild

As Trump bets on tariffs to jumpstart a U.S. manufacturing comeback, the question looms: can America reindustrialize without reinventing the global economy and capping trade imbalances?

There comes a moment in every declining empire when its rulers are forced to face the truth: the engines that once powered their supremacy are sputtering. Factories sit idle, debts mount, and the old playbook—once so reliable—no longer delivers victory. Rising challengers like China and Russia, long dismissed as peripheral powers, have elbowed their way into the top ranks, reshaping the global order as American dominance begins to fray.

This is the crossroads at which the United States now stands. And Donald Trump—whether by gut instinct or calculated gamble—is rolling the dice on a sweeping economic rebuild. On April 2, 2025, he unveiled a bold new tariff regime: a 10% blanket duty on all imports, a 34% surcharge on Chinese goods layered atop existing penalties, and sharp retaliatory tariffs aimed even at traditional allies like the European Union and Israel. It’s a gamble that sacrifices the comforts of cheap imports and debt-driven overconsumption in hopes of rebuilding an industrial base hollowed out by decades of globalization.

Trump has branded it “Liberation Day”—a declaration of economic independence—from the easy life of overconsumption. But the aftershocks have already begun: oil prices are slipping, the dollar is softening, and markets are rattled, shedding a sliver of the inflated gains amassed in the era of easy money and financialization. So far these are positive signs on the road to reindustrialization, but Trump’s tariff gambit is a high-risk reset, with an uncertain horizon—one that may take a decade or more to prove its worth, or to unravel entirely in the fog of a global trade war.

From Dominance to Decline

The United States is caught in a trap of its own design, with the dollar as both crown jewel and Achilles’ heel—a gleaming asset that sustains a lifestyle far beyond the nation’s productive capacity, yet leaves it perilously exposed to internal decay. Cemented in 1971 when Nixon severed the gold peg, the dollar’s reserve currency status grants America unmatched borrowing and spending power. But that privilege comes at a cost: to supply the world with dollars, the U.S. must run chronic trade deficits, steadily hollowing out its industrial core.

This is the Triffin Dilemma on steroids—a structural bind in which the U.S. must maintain both budget and trade deficits to uphold the dollar’s supremacy. The result is systemic overconsumption, roughly 10% above actual output, financed by foreign surpluses—led by China’s relentless export engine, with contributions from dozens of lesser economies. America’s political class has assigned its citizens the role of consumers of last resort, and the average American has grown comfortable in this financially-engineered gluttony. Any genuine effort to close the twin deficits would trigger a depression-scale GDP collapse—an unthinkable prospect no mortal administration has dared approach.

Economist Robert Triffin warned that a global reserve currency comes with a paradox: provide the world with liquidity and erode your own economic foundations; hoard it, and global trade seizes. China understands this all too well—and has no desire to let the yuan inherit the dollar’s burden, avoiding the very trade-offs that have quietly eroded America’s once formidable industrial and geopolitical heft.

But in the wake of China’s rise, a looming debt crisis, and Russia’s impending victory in Ukraine—where it outproduced all of NATO in arms by a factor of three—America’s decline is no longer a matter of alternative media opinion. Like a once-dominant sports franchise now sliding into mediocrity, the U.S. faces a painful rebuild if it hopes to remain in the top tier of global power.

The Pivotal Decade

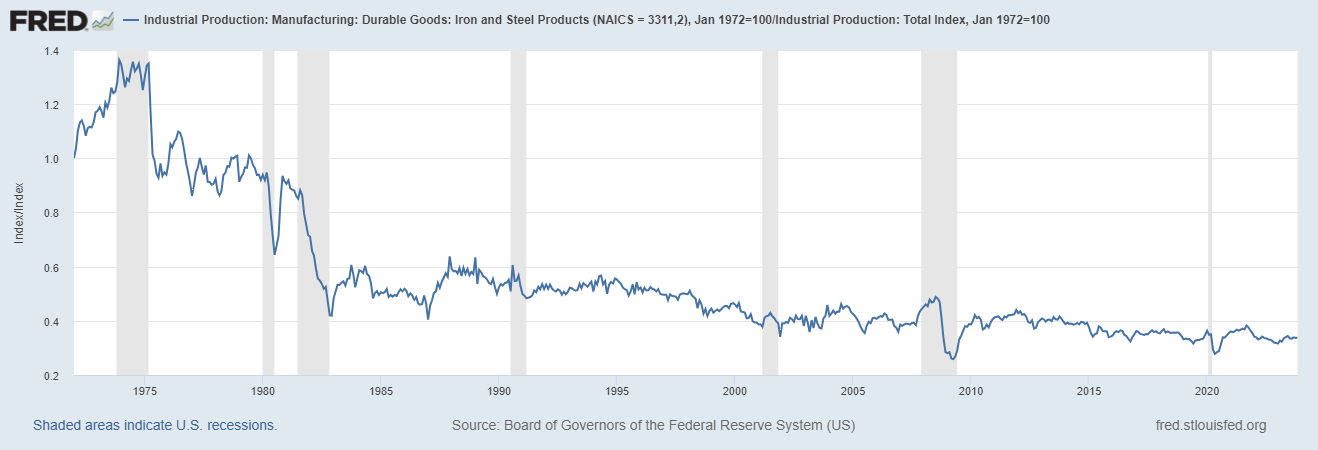

The stakes come into sharp focus when we examine what Trump is trying to undo. As Judith Stein documents in Pivotal Decade, the unravelling began in the 1970s, when policymakers from both parties sacrificed industrial strength on the altar of financialization and Cold War strategy. The creation of the petrodollar system—linking global oil transactions to the U.S. dollar—tilted the economy toward Wall Street, enriching finance while letting Main Street wither. Wealth was funnelled into speculation as the nation’s factories decayed.

Trade frameworks like GATT cemented this shift. While allies like Japan and West Germany protected their markets with subsidies and strategic barriers, American leaders welcomed waves of cheap imports—what Stein portrays not as oversight, but as a calculated choice. In their view, maintaining Cold War alliances outweighed preserving domestic industry. Factory closures weren’t a failure of policy; they were its very outcome. The resulting devastation across the industrial Midwest—what became the Rust Belt—wasn’t unforeseen. It was collateral damage. And it was that damage Trump tapped into in 2016.

Now, his sweeping tariff regime aims to reverse this half-century arc. But Stein’s analysis suggests the challenge runs far deeper. Revitalizing manufacturing won’t be accomplished with tariffs alone. It requires resurrecting supply chains long since dismantled, rebuilding vocational education systems gutted by decades of neglect, and confronting a financial sector that rewards stock buybacks over investment in production.

Stein further traces how the 1970s marked a decisive pivot—from a political economy built on production, union power, and high wages to one premised on consumption and credit. Confronted by stagflation and oil shocks, policymakers abandoned the post-war consensus and embraced a model that relied on cheap imports to contain inflation.

Nixon’s 1971 dollar devaluation, intended to boost exports, backfired as allies like Japan and West Germany doubled down on mercantilist strategies. Washington, preoccupied with détente and global stability, failed to push back. By the end of the decade, American steel and auto industries were haemorrhaging, and cities like Youngstown and Detroit were left behind in a trade war their own government refused to fight.

Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs echo the protectionist pleas of labour unions from that era. But Stein’s chronicle makes clear: the damage wasn’t just economic—it was institutional and ideological. Decades of underinvestment, offshoring, and a cultural shift that valorised MBAs over machinists created an ecosystem hostile to industrial renewal. Tariffs may be the opening salvo, but rebuilding the industrial base that once powered America’s rise will demand a far more comprehensive reckoning with the structural choices made nearly fifty years ago.

Liquidating the Rentier Class

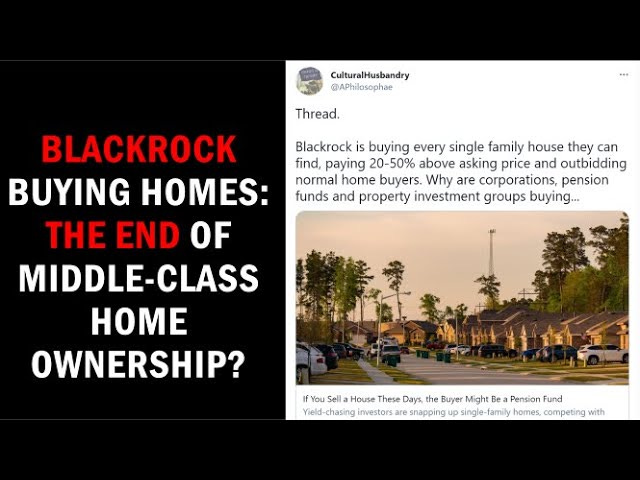

A formidable obstacle to US reindustrialization is the grip of rentier parasites inflating housing, education, and healthcare costs to unsustainable heights. During America’s industrial peak, competitive salaries coexisted with affordable homes, robust public schools, nearly free universities, and efficient private healthcare systems like Kaiser Permanente, which covered working families comprehensively.

Today, the essentials of a stable life—housing, healthcare, education—have morphed into luxuries, with wealth siphoned upward to a bloated financial elite. If Trump is serious about reindustrialization, he’ll need to confront this parasitic class—BlackRock, Wall Street, and their peers—with the same ruthless resolve China has shown in disciplining its own oligarchs. Tariffs are only a starting point. To lay the groundwork for a true manufacturing revival, the financial aristocracy must be dismantled—its parasitical grip on American labour and industry pried loose.

Colonial Precedents

Britain’s fall a century ago offers a sobering preview of the peril America now faces. In the 19th century, Britain was hailed as “the workshop of the world,” its industrial dominance built on locomotives, steam engines, textiles, and global trade. But by the early 20th century, that edge had dulled. Rising powers like Germany and the United States began to outproduce it, eroding Britain’s lead. Desperate to preserve the pound’s global stature, Britain leaned heavily on its empire to mask industrial decline.

The 1919 Key Industries Act imposed tariffs on goods from outside the empire, shielding domestic producers. Meanwhile, colonial resources—rubber from Malaya, cotton from India, gold from South Africa—propped up the shrinking industrial base. The 1932 Ottawa Agreements created a captive market by forcing colonies to buy overpriced British goods. But this was a stopgap, not a solution. Rather than restoring competitiveness, Britain papered over its weakness. By the 1930s, its industrial heartland had hollowed out, debt levels soared, and its overextended empire was already fraying—vulnerabilities that World War II would fully expose.

Crushed by war and economic exhaustion, Britain ceded global leadership to the United States—the new industrial juggernaut. It survived the transition, barely, thanks to its “special relationship” with Washington, which offered aid and strategic cover.

Today, that dynamic has flipped. China now plays the role America once did: an industrial colossus powering global supply chains. And in a historic irony, it was the U.S. that financed China’s rise—outsourcing manufacturing, offshoring capacity, and assuming Beijing would remain a compliant workshop. It didn’t. China has emerged not just as a peer competitor, but a plausible successor.

A New Colonial Model?

One way to read Trump’s tariffs is as a short-term gambit to strong-arm allies into a modernized version of Britain’s colonial trade scheme. In the near term, the U.S. may attempt to compel countries like the European Union, Japan, and South Korea to absorb American goods—regardless of price or quality—as a kind of imperial tribute, intended to jumpstart domestic production. Slashing the budget deficit would normally require curbing military spending—a nonstarter for the Military-Industrial Complex. But what if that burden could be exported?

Washington is already leaning on Europe to funnel 5% of its GDP into American-made weapons—bloated contracts for overpriced jets, obsolete missile systems, and surplus hardware. This isn’t trade; it’s tribute. A geopolitical shakedown masquerading as defense cooperation. The U.S. is exploiting its strategic dominance to offload fiscal burdens and industrial overcapacity onto its allies, effectively asking them to bankroll America’s reindustrialization by overpaying for second-rate output. And why wouldn’t it? Europe, long reliant on American protection, shows little appetite to defend itself when it can outsource the blood and burden to U.S. forces.

Europe, primed by years of threat inflation portraying Russia and China as existential menaces, has largely accepted the logic. Yet it makes little difference if the danger is overstated: Russia’s ambitions are regional, China’s are economic. The quality of the weapons is irrelevant—they’re not meant to be used, only bought. They are symbols of submission in a transatlantic relationship increasingly defined by coercion rather than partnership.

As tariffs rise and demands for military purchases grow, Europe doubles down—confusing dependence with security. Japan and South Korea, tied to U.S. defense pacts, face the same pressure: to keep Washington happy, they must buy American, even at the cost of their own industrial competitiveness.

The consequences are predictable. Europe—and to a lesser extent, Asia—will continue to hollow out. Financialization will deepen as capital flows to the U.S. to finance the deficits born of this enforced patronage. Germany’s recent unravelling is an early warning. Since the U.S.-linked sabotage of the Nord Stream pipeline in 2022, its industrial engine has sputtered, energy costs have soared, and trade surpluses have vanished—redirected westward.

This isn’t alliance; it’s extraction. A neo-imperial squeeze without the formal trappings of empire. For the U.S., it’s a desperate lifeline: selling subpar goods to captive markets to buy time for a true industrial revival that may never come. Whether America’s allies will endure this long enough for it to regain its footing—that’s the high-stakes wager behind Trump’s tariff play.

Saving the Dollar: Keynes’ Bancor Concept

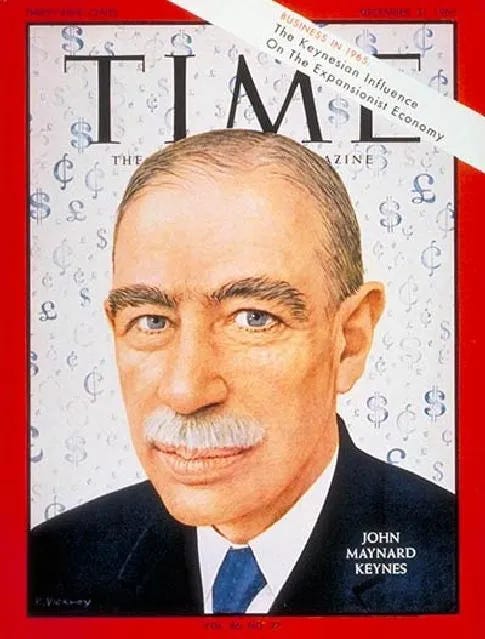

Trump’s tariffs, though a blunt short-term instrument, expose a deeper dilemma: how to rebalance the global economy without simply replacing one hegemon with another. The dollar’s dominance—fuelling America’s deficits and deindustrialization—is unsustainable, yet a yuan-led order threatens to reproduce the same asymmetries under a different flag. A forgotten alternative lies in John Maynard Keynes’s 1940s proposal for the Bancor, a supranational trade device envisioned at Bretton Woods but ultimately cast aside in favour of a dollar-centric system. Today, Keynes’s model offers a path to stabilize a global economy distorted by imbalances too deep for tariffs alone to fix.

The Bancor wasn’t merely a new currency—it was a structural mechanism for restoring balance. Issued by an international clearing union, Bancors would serve as trade credits and debits: nations earning them through exports, spending them on imports. Crucially, persistent surpluses (like China’s) and chronic deficits (like America’s) would trigger penalties—interest charges or currency adjustments—designed to correct the underlying asymmetries. Keynes aimed not to punish trade but to prevent it from becoming an engine of dominance.

Think of it as a salary cap for the global economy: just as sports leagues impose spending limits to level the playing field, the Bancor would limit imbalanced trade, nudging countries toward economic equilibrium. Surplus nations would be incentivized to revalue currencies or boost domestic demand; deficit nations to curb consumption or invest in production. Unlike today’s dollar-driven system—where the U.S. overconsumes and China overproduces—the Bancor would align incentives to correct, not entrench, structural flaws.

Importantly, this wouldn’t require abandoning the dollar overnight. The greenback could retain its symbolic reserve role, preserving U.S. prestige, while actual trade settlement occurs in Bancors—decoupling global trade from the domestic distortions of any single economy. The U.S. could eventually rebuild its industrial base without coercing allies; China would be compelled to pivot inward, moderating its export-driven model. It wouldn’t end geopolitical competition, but it could defuse the currency wars and economic coercion that Trump’s tariffs now risk inflaming.

Reviving Keynes’s vision wouldn’t just update the plumbing of the global economy—it could offer a principled way out of a system warped by decades of dollar privilege and the absence of accountability for imbalance. In an era grasping for a new order, the Bancor may be the best forgotten idea whose time has finally come.

A very insightful analysis, which is lacking in the dominant and the alt media.

BRICS++ is the 21st Century "Bancor" shaped and fitting for current geopolitical trade and economics.