Tides of Economic Change

Jake Sullivan's speech on international economics finds the US caught between capitalist cycles: the receding ebb tide of US financialization is superimposed upon by a Chinese wave of manufacturing.

US national security advisor Jake Sullivan recently gave an extraordinary speech on international economic policy at the Brookings Institution in Washington DC. Sprinkled liberally with partisan boilerplate; nevertheless, the speech is worthy of study as an obituary of the US-led era of unipolar globalization. Sullivan blames “non-market” economies such as China for forcing the US to now reject trade liberalization and the off-shoring of production. In its place Sullivan hints at, but never details, an era of protectionism, a US Industrial Policy, massive internal investments, and the return of manufacturing—all in the name of confronting the red menace of China.

The speech is a tacit admission that much of Donald Trump’s 2016 platform, at the time considered dangerous heresy, is now establishment orthodoxy. The once unthinkable notion of an American Industrial Policy is now, according to Sullivan, a geopolitical imperative. Sullivan proudly proclaims a coming era of unabashed economic nationalism for the US. He outlines a US-led global order that is clearly intended as an alterative to BRICS+ by financing infrastructure projects on the global periphery. He highlights the I2U2 Group, uniting Israel, India, US, and UAE. In doing so Sullivan now admits the American unipolar moment is over and that we are now in at least a bipolar global structure, a struggle where former “market” economies mimic the strategies of “non-market” economies.

Crucially, Sullivan’s speech marks a rhetorical rejection of US financialization and embraces a return to production, which in quoting Joe Biden, Sullivan calls “building.” However in a major disappointment, Sullivan subordinates domestic economic policy to foreign policy, “President Biden’s core commitment—indeed, his daily direction to us—to more deeply integrate domestic policy and foreign policy.” A better approach is to prioritize domestic economic power, which will in turn inevitably lead to geopolitical power. Simply “integrating” it will lead to domestic strongholds being sacrificed on the altar of foreign policy gains. This is what occurred in the 1970’s as the US steel and automotive industries were traded to Japan and Europe in return for their continued support in the fight against communism.

The primary focus of Sullivan’s speech is maintaining the current US supremacy in the global semiconductor industrial ecosystem. Not for the holistic health of the US economy as a whole, but for national security reasons. US innovation and high tech prowess developed this technology, aided by plenty of government seed money. The Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), funded research into breakthrough technologies that resulted in the internet, stealth technology, personal computers, guided munitions, drones, and GPS among many others. The stunning success of DARPA has inspired many other nations, in particular the People’s Republic of China, to fund innovative emerging technology.

Dominant military technology serving as the weapons of a fractured and deteriorating society is not a long-term winning formula. The key to the success of this “Biden Doctrine” will be if economic nationalism is spread much further than just protecting the vital semiconductor industry. The signs are not positive as Sullivan never addresses the true American diseases: overconsumption and underproduction. The history of the capitalist era shows that exporting nations create power while importing nations bleed it.

The Speech

Sullivan lays out the four major challenges the US faced as Biden entered office:

First, America’s industrial base had been hollowed out.

The second challenge we faced was adapting to a new environment defined by geopolitical and security competition, with important economic impacts.

The third challenge we faced was an accelerating climate crisis and the urgent need for a just and efficient energy transition.

Finally, we faced the challenge of inequality and its damage to democracy.

The first “hollowed out” and final “damage to democracy” points are recognition that abandoned post-industrial communities are not going to vote for an aggressive US foreign policy, nor are they likely to send their sons to die in the South China Sea, let alone the Donbass. The authoritarian option of indicting or jailing “dangerous” opposition leaders will only lead to further radicalization of the disgruntled in America. Given the lack of a substantial engagement with these first and final points, the only conclusion is that including them is a weak attempt on Sullivan’s part to co-opt anti-systemic challenges to the US political establishment.

What is clear, as would be expected from an economics speech given by the head of US foreign policy, is that fixing the economy is being driven by short-term foreign policy needs. What is missing is a deeper understanding that long-term geopolitical power emerges from the loading docks of factories.

Sullivan’s solutions are centered around protecting US dominance in the microchip sector. He argues that following the rules of the Washington Consensus—trade liberalization and market freedom—will doom this sector to eventual Chinese control. He accuses China of practising “non-market” strategies such as subsidizing industries and controlling imports. In short, like all successfully rising economies, China practises economic nationalism. Historically the US did exactly the same thing with the American System.

Sullivan articulates a “small yard, high fence” concept of limited, but severely strict protectionism, around the most powerful semiconductor supply chains. Elsewhere he hints at broader protectionist measures but never provides any details.

Twice Sullivan mentions the US must remain competitive in the recruitment of international talent, in other words to stay active on the human capital free agent market. Never does Sullivan say that the US must make the investments and reforms of its own educational system to produce homegrown technical talent.

Capitalist Cycles

Sullivan does not embed his economic ideas into the historical context of capitalist cycles. As Fernand Braudel and Giovanni Arrighi, among many others, have emphasized in their work, capitalism works in both secular and cyclical trends. The secular trend is one of ever larger nation-state epicentres of capitalist accumulation. The journey from Northern Italian, Dutch, British, and American centers of power is capitalism’s secular progression. China, as the greatest manufacturing economy in global history, is now the epicenter of global industrial capitalism.

Each capitalist hegemony goes through two cycles, first a productive manufacturing stage and then, once the rate of profits starts to decline, a financialization cycle. As finance takes control, capital flows outward to seek cheaper labour and higher profits and inevitably finances the next epicenter of capitalist power. From Giovanni Arrighi’s Adam Smith in Beijing:

One is the tendency of over-accumulation crises to bring about long periods of financial expansions which, to paraphrase Schumpeter, provide the means of payments necessary to force the economic system into new channels. As Braudel underscores, this tendency is no novelty of the nineteenth century. In sixteenth-century Genoa and eighteenth-century Amsterdam, no less than in late nineteenth- century Britain and the late twentieth-century United States, "following a wave of growth . . . and the accumulation of capital on a scale beyond the normal channels for investment, finance capitalism was already in a position to take over and dominate, for a while at least, all the activities of the business world. While, initially, this domination tends to revive the fortunes of incumbent capitalist centers, over time it is a source of political, economic, and social turbulence, in the course of which the existing social frameworks of accumulation are destroyed; the "headquarters of the capitalist system," in Schumpeter's sense of the expression, are' relocated to new centers; and more encompassing social frameworks of accumulation are created under the leadership of ever more powerful states. (p. 93)

This power transfer begins with formerly profitable economic sectors attracting too much competition and then being sent off to the periphery. China is currently climbing the value ladder, seeking ever higher and more technically advanced areas of production. Having recently risen to a dominant position in the manufacturing of electric cars, China’s highest priority now is independence from US-controlled semiconductor supply chains. But these chip technologies are both extremely challenging and always advancing forward, driven by Moore’s Law.

One of the key national security goals of the Sullivan speech is “decoupling” China away from the latest and most powerful microchips and the complex industrial machinery needed for their manufacturing. The US and allies seek to maintain a “chip gap” with China of several generations in order to frustrate Chinese development of high-tech weaponry and Artificial Intelligence (AI) capabilities. China’s primary role in the microchip supply chains is as the consumer of last resort. Blocking sales to China implies a bifurcation of the global economic system into separate blocs. But in the meantime corporate profits of US semiconductor giants are being hit by the ban on high performance microchip sales to China.

From social prosperity to a hollow void

The previous cyclical transition from financialization (British) to productivity (US) occurred at the end of WW2. This was also a time of global bifurcation into two blocs. American leaders feared the Marxist menace in the Soviet Union and so offered a peace deal to the American working class. From Minqi Li’s China and the 21st Century Crisis written in 2015:

The post-1945 “New Deal” included a “capital-labor accord”, a welfare state, and Keynesian macroeconomic policy. The “capital-labor accord” promised that the Western working classes could expect steadily rising real wages in proportion with the growth of labor productivity. In return, the working class would refrain from challenging the capitalist ownership of the means of production. The welfare state provided that the government would guarantee a minimum lifetime income (in the form of pensions and unemployment benefits) and cover a substantial portion of the cost of labor power reproduction (in the form of socialized education and health care). In addition, the government was expected to use Keynesian macroeconomic policy to ensure a reasonably high level of employment. (p. 6)

“Labor power reproduction” refers to post-WW2 family policies that allowed the baby boom to occur. Worker salaries were high enough to allow a single bread-winner to comfortably raise a large family. This led to a flourishing industrial base and relative social harmony. But eventually this prosperity led to decreasing profit margins:

By the 1960s, strengthened by the long economic boom and welfare state institutions, the western working classes demanded an even bigger share of the world surplus value. The semi-peripheral working classes (in the former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and Latin America) also demanded a share of the world surplus value. Squeezed by higher wages, higher taxes (to pay for the welfare state expenditures), and rising energy costs, global capitalism was in deep crisis. The global capitalist classes responded with a counter-offensive. (p. 7)

In the 1970’s the tidal wave from the American production stage, that had deposited so much wealth and power, cycled into an ebb tide of financialization, as accumulated middle class prosperity started flowing outward back towards the rest of the world:

The essence of “neoliberalism” was the dismantling of the global social contract established after 1945 (the “New Deal”) in order to recreate favorable conditions for global capital accumulation. The neoliberal triumph in the 1990s led to the global redistribution of income from the workers to the capitalists. The drastic decline of living standards in many parts of the world reduced the global level of effective demand. Trillions of dollars of speculative capital flowed across national borders, generating financial bubbles followed by devastating crises. The neoliberal global economy was threatened by the tendency towards stagnation and amplified financial instability.

In the late 1990s and the early 2000s, the United States acted as the “consumer of last resort” for the global economy. The US current account deficits helped to absorb surpluses from the rest of the world, allowing China, Japan, and Germany to pursue export-led growth. Within the United States, economic growth was led by debt financed household consumption. The global economic expansion in the early 2000s rested upon a set of financial imbalances that soon became unsustainable. (p. 3)

Nowhere in his speech is Sullivan offering a “New Deal” of any sort outside of rhetorical recognition of hollowed-out communities. Sullivan avoids these uncomfortable cyclical issues and prefers to linger over the one area of indisputable US geopolitical power: the semiconductor industry. But the key economic question of the coming decades is how the United States will rebalance its economy away from the consumption trap?

The Consumption Trap

G.W.F. Hegel’s master / servant parable is an uncanny description of the evolving relationship between the US and China. Often mistranslated as master / slave, one of its many possible readings is the dialectical relationship between consumption and production. Two feral men—caught in the gap between nature and humanity—fight to the death in an archaic forest in a battle for recognition. The man whose animal instincts for survival trump his human desire for recognition surrenders. He accepts a state of economic bondage in service to the triumphant master, whose deepest strength is his all-too-human desire for recognition from another man, which once achieved, creates self-consciousness within himself.

That means that truly human desire would overcome the most basic and most significant animal desire, the desire to preserve life. Truly and thoroughly human desire means desire orientated toward another desire without concern for the preservation of life, without concern for one's animal desire -- in other words, desire seeking recognition even at the risk of life. Two men, or two desires, confront one another in this fight, and one of the two will establish himself as the superior, the other as inferior: he who is not willing to sacrifice his life in this struggle, giving in to the other, establishes that he is still bound to the natural, still essentially slavish; while the other, willing to sacrifice life for a non-vital end, recognition, establishes that he is master over himself, and master over the other. Thus, while the master will be recognized by the servant, the servant will not be recognized by the master.

Once in service to his master, the servant learns to skilfully manipulate the natural world and produces goods for his master’s consumption.

[T]he master is not truly satisfied by the recognition of the servant. Nevertheless, the master forces the servant to work for him, and thus the master has the benefit of enjoying and consuming the product of the servant's work -- the master idles away his time in partial satisfaction; the servant toils away in service to the master. While the servant works, he works upon (i.e. he becomes master of) nature. The servant became a servant because he was subject to nature, or unwilling to sacrifice his life for a non-natural end. Through work, however, the servant overcomes nature, and overcomes his own nature as well: in order to work and produce a product for the consumption of the master, the servant must repress his natural instinct to consume the material. The master had overcome nature and himself by risking his life for a non-vital end, had become master over the servant, who had shown his servileness by being tied to nature. Now the servant overcomes nature and his own nature through work. The master's action was destructive simply, while the servant's action, work, destroys in order to create -- he does not destroy but rather he sublimates. Progress, technological and historical, requires this sublimation that is work, which is to say that it presupposes the era of mastery and service. The master remains identical to himself, he is required to spark the historical process, but he doesn't get anywhere. The servant will ultimately become the ‘absolute master’, satisfied by a universal recognition, rather than the sort of first-moment master who is doomed to remain unsatisfied.

China’s Century of Humiliation (roughly from the Opium Wars to the Communist Revolution) represents her fight and ultimate surrender into a servile acceptance of Western mastery.

After several decades of Maoist orthodoxy, a counter-revolution in the late 1970’s transitioned China towards a market economy just as the West was launching neoliberalism. As Minqi Li states:

China’s counter-revolution changed the global balance of power. The “opening up” of China made it possible for the western industrial capital to be relocated to China, exploiting China’s massive cheap labor force. By the beginning of the twenty first century, China became the center of global manufacturing exports.

This transition allowed the US to run increasingly large trade deficits, which means Americans consume more than they produce. Of course, decades earlier the opposite was true, when America ran huge trade surpluses, she had to suppress domestic consumption to gain foreign markets and accumulate both capital and power. Minqi Li explains how today the US benefits from its trade deficit:

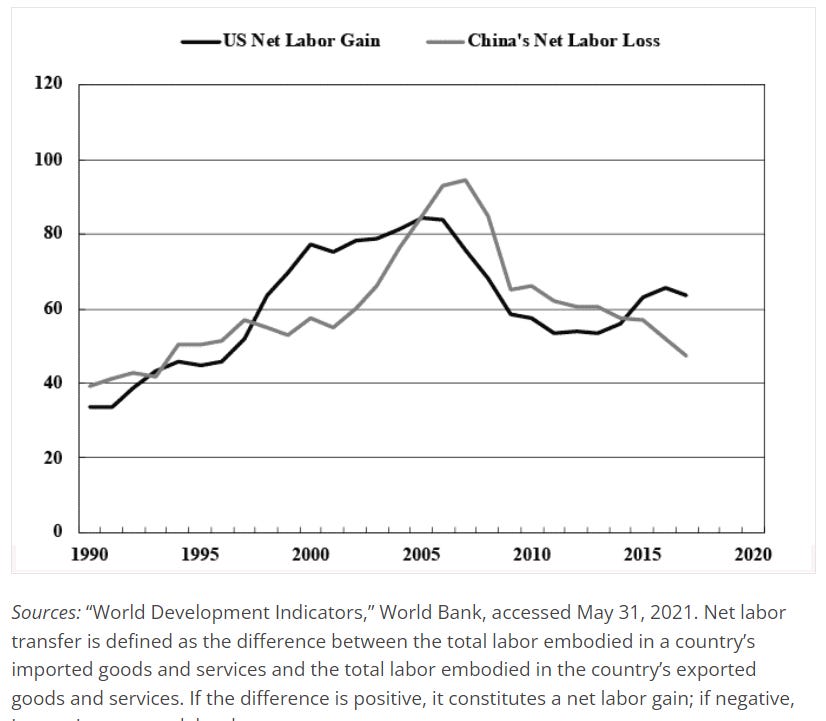

In 2017, the U.S. net labor gain was sixty-three million worker-years and China’s net labor gain fell to forty-seven million worker-years.

<…>

Had there not been unequal exchange, the massive amounts of material goods currently supplied to the United States by the rest of the world would have to be produced through domestic production to maintain existing levels of U.S. material consumption. About sixty million workers (38 percent of the total U.S. labor force) would have to be withdrawn from service sectors and transferred to material production sectors. This would result in a massive reduction of services output (by about two-fifths of U.S. GDP) without raising levels of material consumption.

The transition Minqi Li describes will happen one way or another. China’s rising salaries and standard of living mean one day she too will start consuming more than she produces. In a few decades, China will start championing free trade and start running a trade deficit, just as all previous capitalist hegemons have done. The exceedingly difficult challenge for the United States is to perform the opposite trick, to return to manufacturing so that trade can be at least balanced and geopolitical power can stop leaking towards the rest of the world.

Beyond Master and Servant: Distributism

As the gap between the wealthy and others has increased during this terminal phase of US financialization, working habits have adapted. A job for life is a distant memory. With the recent technological revolution, individuals are increasingly free from traditional employment patterns. This trend acceletated with the pandemic and working from home. People, in particular men, are ”dropping out” of the corporate rat race in what some call the Big Quit. This coincides with men increasingly avoiding higher education:

American colleges and universities now enroll roughly six women for every four men. This is the largest female-male gender gap in the history of higher education, and it’s getting wider. Last year, U.S. colleges enrolled 1.5 million fewer students than five years ago, The Wall Street Journal recently reported. Men accounted for more than 70 percent of the decline.

Some of this is just churn between jobs but many people are starting their own small businesses. This phenomenon will only increase as Artificial Intelligence makes redundant large numbers of the “laptop class.”

Such jobsite fragmentation should help undermine the master / servant dichotomy. In capitalism, the means of production are owned by a small oligarchic master-class. In socialism property is concentrated into state hands. A sublimation of the master / servant dialectic entails both roles being embodied in the same person: the small business person, who owns a fragment of the means of production.

Widespread small property ownership is the fundamental concept behind Distributism. Michel Houellebecq, in his novel, Submission imagines a future France under the rule of a moderate Islamic Party and its President Ben Abbes, who is a powerful advocate for Distributism. Houellebecq describes the days following Ben Abbes election victory:

Beneath these surface agitations, France was undergoing deep and rapid change. It turned out that some of Ben Abbes’s ideas had nothing to do with Islam: during a press conference he declared (to general bafflement) that he was profoundly influenced by Distributism. He had actually said so before, several times, on the campaign trail, but since journalists have a natural tendency to ignore what they don’t understand, no one had paid attention and he’d let it drop. Now that he was a sitting president, the reporters were forced to do their homework. So, over the next few weeks, the public learned that Distributism was an English economic theory espoused at the turn of the last century by G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc. It was meant as a ‘third way’, neither capitalism nor communism – a sort of state capitalism, if you like. Its central idea was to do away with the separation between capital and labour. For Distributists, the basic economic unit was the family business; when in certain sectors consolidation became necessary, the government had to ensure that the workers remained the owners and managers of their own enterprise.

Houellebecq goes on to explain how officials in the European Union would react to Distributism:

It soon became clear that although their doctrine [Distributism] was avowedly anti-capitalist, Brussels wouldn’t have much to worry about. The main practical measures adopted by the new government were, on the one hand, to end state subsidies for big business – which Brussels had always fought in the name of free trade – and, on the other, to adopt policies that favoured craftsmen and small business owners. These measures were an instant hit: for decades, every young professional in the country had dreamed of starting his own business, or at least of becoming his own boss. The measures also reflected changes in the national economy: despite the costly efforts to save heavy industry in France, factories continued to close, one after the other, so farmers and craftsmen managed to compete and even, as they say, to grow their market share.

Small family operations internalize the class war between capitalist and worker within each individual. In the morning she is the boss, in the afternoon the worker, and in the evening the marketing executive; and before going to sleep, she takes care of the accounting duties. Since the foundational principle of Distributism is the mass fragmentation of property, there is a sort of tethered meridian of wealth distribution embedded within its concept. Interestingly China currently features strong protections for small business against disloyal competition by large firms.

And while a radically non-radical idea such as Distributism is hardly likely to appear in any future speeches by US national security advisors, the problem remains of how America is going to survive any eventual rebalancing of trade. With social cleavage already so large, and political power so concentrated in the few, this coming rebalancing act will very likely be done on the backs of the former middle class. To avoid this, people must already prepare by downsizing and acquiring property. If enough follow suit, by 2030, people will own something and be happy—and very busy.