Riding the Wake of Suicide Sanctions

A conceptual blueprint for a multipolar reserve currency regime apt to check the greenback's exorbitant privilege/burden.

As President Xi was leaving the Kremlin, his parting words to Russian President Putin set their summit into a larger historical context:

“Right now there are changes – the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years – and we are the ones driving these changes together,” Xi told Putin as he stood at the door of the Kremlin to bid him farewell.

The Russian president responded: “I agree.”

President Xi received a doctorate degree in Marxist Ideology in 2002. The Chinese leader’s comments bring to mind those of Lenin, “there are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.”

Roughly a hundred years ago, the Russian Revolution brought Marxists to power. But it took the Chinese to demonstrate that Communism is not an alternative to Capitalism—in Marxist theory Communism is Capitalism’s presumed happy ending. Early in the 20th century, as Lenin was founding the Soviet Union, the United States was culminating its climb to global supremacy. While history can only be told from a certain distance, this Xi-Putin summit may one day be seen as a key milestone in the US’ recent descent towards less lofty global heights.

A key item on the Xi-Putin agenda was an agreement to build the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, which will deliver to China a portion of the cheap gas which previously fuelled European prosperity. Unlike the hysteria in Europe, no one in Beijing claims Russian gas supplies will be a “weapon.” Instead they see it as just one more competitive advantage China will have over the rest of the world thanks to the increased capital accumulation this inexpensive gas will bring.

The US tactical objective of building a barrier between Germany and Russia has now been achieved. Going forward, Europe will have to pay four times more for American LNG shipments than they would have for that “weaponized” Russian gas. But the cost of this tactical win is a huge defeat on the strategic level for the US. Russia and Europe combined were never going to be a strategic threat to US power. Clearly China-Russia together are. That cheap gas, and the capital accumulation it will fuel, is now indeed a key weapon abetting the Primal Horde’s quest to displace the US from its throne of global power.

The first victim of churning global power relations may be the dollar system. Currently other nations of the world are forced to pay massive levels of “imperial tribute” to the US through purchases of US debt. But at the outbreak of war in Ukraine, the US and allies froze more than $300 billion in Russian monetary reserves. Together with blocking Russia from SWIFT, reactions to these suicide sanctions are boomeranging back on the West.

While Xi and Putin were clinking champagne glasses, the West was struggling to contain a growing banking crisis, which in turn is threatening the US dollar’s position of global reserve currency. While the long-term cause of the West’s financial troubles is persistent US deficits, a powerful contributing factor to the banking crisis is the inflation-inducing sanctions. While sparking “Putin’s price hike” in the West, the sanctions failed to reduce the Russian ruble to rubble. Silicon Valley Bank collapsed because its capital reserves were based on pre-sanctions low-yield bonds, which lost value with each rate hike the Federal Reserve Bank was forced to enact in response to rising inflation.

Credit Suisse’s (CS) collapse was triggered by wealthy individuals withdrawing deposits after CS “froze” several Russian bank accounts. With tensions rising between the US and the Rest of the World, rich Chinese and Middle Eastern investors executed a bank run in order to seek sanctuary from future US financial coercion.

Russia successfully defended itself from sanctions by achieving just enough monetary autonomy. This financial safe space remained beyond the the stinging whip of US sanctions. This sanctuary also quarantines Russia from contagion by sick Western banks. During their summit, Russia agreed to use the yuan earned from China through energy sales to settle trade with Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Step-by-step the Chinese yuan is becoming an important means of exchange for the multipolar Primal Horde. Meanwhile the BRICS+ bloc is working on future monetary arraignments fit for a multipolar world.

The US has spent the 21st century flailing across the globe deploying hard power in the form of invasions and coercive sanctions. In response China and Russia have been shrewdly employing compound soft power, a concept developed by American scholar Giulio Gallarotti, through multilateral organizations such as BRICS+ and the One Belt, One Road Initiative. Even the Russian use of hard power in Ukraine has reinforced BRICS+ soft power by triggering harsh Western countermeasures. These have not only failed to hurt Russia, but have further unified the rest-of-the-world, who after suffering centuries of Western malice, are now repulsed by what they see as an overbearing and hypocritical Western response to Russia’s invasion.

A key BRICS+ soft power target is shelter from dollar hegemony. Global reserve currencies have been rising and falling since Byzantine bezants first appeared in the 5th century. History shows that the world has a need for such monetary devices. But with great monetary power comes great responsibility. No one likes the idea of one nation or empire unfairly profiting from their currency. But in the good times, this seems a small price to pay for the economic growth and convenience such a currency provides. But money is best when, like a referee, it is not noticed. Good monetary regimes should induce a stable inertia into the global economy. As Benjamin J. Cohen explains in Currency Power:

In fact, currency choice is notoriously subject to inertia owing to the often high cost of switching from one money to another. The same network externalities that promote the use of a first mover can long delay the rise of other currencies. Why would market actors go to the trouble of adapting financial practice to a different money unless they can be sure that others will make use of it, too? A challenger must not just match at least some of the qualities of existing international currencies. It must somehow also offer advantages sufficient to persuade agents to risk making a potentially costly change. (p. 14)

But when the leading currency wobbles, or is used as a sanctions whip—sleepy systemic inertia turns into an agitated desire within many to overturn the system. The first rebel goal is to seek autonomy from the corrupted dominant currency regime. These protective arraignments may then serve as the seed of a new reserve currency. But climbing to the top levels of global money is a Darwinian drama. The new system must survive a ruthless battle of monetary fittest to reach the top of the currency pyramid.

China-Russia lead a growing multipolar alliance. And so the idea of simply replacing the US dollar with the Chinese renminbi is to stay locked within the ideological framework of unipolarity. Instead of a Chinese “redback” replacing the US “greenback” a richer mix of currency devices may be required to nourish a multipolar economy.

The renminbi (People’s Currency) is China’s currency while the yuan is the currency’s unit of account. While the US dollar is both the name for the American currency and its unit of account, in Britain the currency is sterling and its unit of account is the pound.

One of the first paths towards understanding currency multipolarity is to examine the three functions of money and the three historic money forms that follow these functions.

Grand Currency, Ghost Money, and Petty Coin—the Three Forms of Money

As every economics undergrad is taught, money serves three functions: it stores value, it forms units of account, and acts as a medium of exchange. When a cache of gold coins is buried; when China buys US Treasures; or when a worker manages to deposit a portion of his or her pay check into a bank, money as acting as a store of value. Stability, or to express it negatively, resistance to change, is a key quality sought for a store of value. A grand currency (moneta grossa) should weather all economic storms and retain its value in the face of inflation. Gold is traditionally the metal most associated with grand currency, although in less wealthy societies silver can play this role. But the high value of gold means grand currencies appear in very large denominations. While facilitating major transactions is vital for governments, aristocrats, and international trade, most people require much smaller denominations to conduct their modest day-to-day exchanges.

Petty coin, typically copper, serves as a medium of exchange. Today’s pennies are a much diminished legacy of petty coin. Traditionally, copper currency served the domestic economy of a typical worker. In medieval times, salaries, rents, and commodities would have all existed within the petty coin range. Unlike today, most common folk in the Middle Ages rarely had any use for the higher forms of money.

But given the tiny value of copper coins, when larger loans were issued, they were often denominated in “ghost money” such as a ‘pound’—a unit of account that didn’t actually exist in actual money form. Many commodities were also priced in the ghost money as this allowed repayment of loans to be effected in barter as well as coin. Silver is the archetypical unit of account metal around the globe and throughout history.

The most famous example of ghost money is the pound (libra in Latin). They first appeared in the Carolingian reforms in the late 8th century. Western Europe was still deeply immersed in the Dark Ages and so issued no gold coins. Charlemagne introduced into his empire the now familiar libra (pound), solidus (shilling) and denarius (penny) monetary alignment. The penny was conceived of as 1/240 of a “pound”. But there were no pound or schilling coins, these two devices were simply units of account. If a large loan was issued to a peasant, instead of listing the number of pennies, the loan would be booked in units of pounds. This not only simplified accounting, it allowed repayment in other commodities which would also be priced in pounds or schillings.

The fixed ratios of the Carolingian system were 1 pound = 20 schilling = 240 pennies. In a small steady-state medieval economy, the fixed Carolingian system functioned well enough. But as Western Europe emerged from the Dark Ages and economic activity increased, it became clear that this system of rigid ratios was not feasible. With the emergence of capitalism, and its associated economic growth, a gold coin was also needed in Western Europe. So the monetary system required three moving parts.

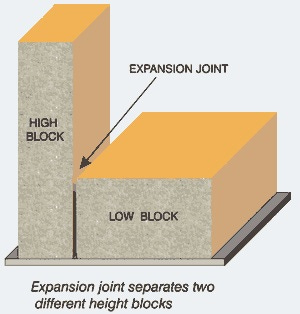

In architecture, a skyscraper often has a low building attached to it. For example a high-rise hotel may need a large conference centre near the ground floor. While these two building forms need to be attached to allow circulation, the structural movements between them may be radically different. For example the heavy tower may sink deeper into the ground than the lighter low-rise conference centre. Such differential movement would create cracks and risk system failures if it transferred between buildings. A movement joint is required between the two extremes.

A monetary system must provide the same flexibility. The silver level—the unit of account—typically acts as the monetary movement joint. First there is a ratio fixed between the “high-rise” of gold and silver. In Ancient Rome this ratio varied between 8 and 12 ounces of silver per 1 ounce of gold. In Western Europe up into the 19th century the ratio was around 15:1.

At the same time the “low-rise” of copper must be allowed to adjust to economic conditions. As economic growth surges or wanes, the amount of petty coin must vary. This is best accommodated by a free floating ratio between silver and copper. Traditionally pennies were set at a 1:240 ratio but this was not flexible since the original pennies consisted of 1/240th of a pound of silver. In other words, the value of a silver penny was intrinsic. A silver penny was both money and a commodity. So in hard times the peasants would hoard pennies and coin shortages would cause deflationary pressures which destabilized the system. As more coins were minted to facilitate exchange, these coins in turn would be cached away, leading eventually to inflation in the system’s store of value function.

Only once these pennies were struck in copper, in a metallic value much lower than their money value, did the needed flexibly appear between the units of account and the medium of exchange: between the silver and copper levels of a monetary system.

Of course this flexibility of petty coin values was often used as a weapon of class warfare. It was in the interest of those holding loans priced in the silver device to increase its ratio to copper. So for example if traditionally 240 pennies were needed to pay back a pound of debt, aristocratic forces would often manipulate this ratio to say 400 pennies per pound. If a manufacturer was producing commodities to be sold in silver, there was a strong incentive to devalue the petty coin paid for wages. Copper coin devaluations often led to popular rebellions.

We see a similar phenomenon today globally between strong and weak currencies. In Iceland during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), mortgages were priced in dollars but repayment was effected in Icelandic krona. When the ratio of dollars to krona became higher, many people were unable to pay back their loans. A similar scenario appears in many developing nations. The rich live their lives in dollars while the poor struggle to survive in their petty local currencies. If a poor nation wants to buy oil, it cannot do so in its “copper” currency, it must buy dollars to make essential purchases.

Let There Be Money—Fiat Currency

Once pennies stopped being minted with a quantity of metal equivalent to their money value, their worth became dependent on the currency issuer’s word. Fiat money has little to no intrinsic value. The qualifier “fiat” comes from a phrase in The Book of Genesis. “Dixitque Deus fiat lux et facta est lux” can be translated into English as, “And God said, ‘Let there be light” and there was light.” Fiat currency derives its value from belief in the declarations of a transcendent, God-like issuer of currency, that these printed pieces of paper or coins have their apparent value. “Let there be money” and the Fed saw that the money was good.

In 1270, Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis, began the process of issuing the world’s first fiat paper money currency. Up until that point China had primarily used copper coinage for their domestic economy, while foreign gold and silver circulated freely to serve the higher monetary functions. In 1270, the Great Khan demanded a monopoly over the production of circulating money. He made all other forms of currency illegal, particularly foreign gold and silver coins. He also made it illegal to refuse his money and he demanded taxes be paid with it. Although the Chinese people did have limited previous experience with paper money, they were hesitant to abandon their copper coin system. Khan built warehouses in each region and stuffed them full of gold and silver. People were told their new paper money was “convertible” to silver whenever they wanted. These reserves at first matched the value of the notes issued. As Marco Polo gushingly described the system:

With these pieces of paper, made as I have described, he [Kublai Khan] causes all payments on his own account to be made; and he makes them to pass current universally over all his kingdoms and provinces and territories, and whithersoever his power and sovereignty extends. And nobody, however important he may think himself, dares to refuse them on pain of death. And indeed everybody takes them readily, for wheresoever a person may go throughout the Great Khan’s dominions he shall find these pieces of paper current, and shall be able to transact all sales and purchases of goods by means of them just as well as if they were coins of pure gold. And all the while they are so light that ten bezants’ worth does not weigh one golden bezant.

Furthermore all merchants arriving from India or other countries, and bringing with them gold or silver or gems and pearls, are prohibited from selling to any one but the Emperor. He has twelve experts chosen for this business, men of shrewdness and experience in such affairs; these appraise the articles, and the Emperor then pays a liberal price for them in those pieces of paper. The merchants accept his price readily, for in the first place they would not get so good a one from anybody else, and secondly they are paid without any delay. And with this paper-money they can buy what they like anywhere over the Empire, whilst it is also vastly lighter to carry about on their journeys. And it is a truth that the merchants will several times in the year bring wares to the amount of 400,000 bezants, and the Grand Sire pays for all in that paper. So he buys such a quantity of those precious things every year that his treasure is endless, whilst all the time the money he pays away costs him nothing at all. Moreover, several times in the year proclamation is made through the city that anyone who may have gold or silver or gems or pearls, by taking them to the Mint shall get a handsome price for them. And the owners are glad to do this, because they would find no other purchaser give so large a price. Thus the quantity they bring in is marvellous, though these who do not choose to do so may let it alone. Still, in this way, nearly all the valuables in the country come into the Khan’s possession.

It’s easy to see a parallel between Khan’s system and the current US monetary regime where the nations of the world convert their wealth into green pieces of US paper.

And as Cicero once noted, “The sinews of war are infinite money.” War broke out, sometime after Marco Polo’s account. The precious metals reserves were removed from the provincial warehouses and taken to the capital, where they served to pay troops and buy weapons. Khan ended any conversion back to silver. At this point the only thing backing his paper money was his word. This was the fiat moment.

Within a few years the wars intensified, the precious metals warehouses were spent and inflation skyrocketed. Khan’s paper yuan lost 90% of its purchasing power leading the entire system to eventually collapse.

History of Reserve Currencies

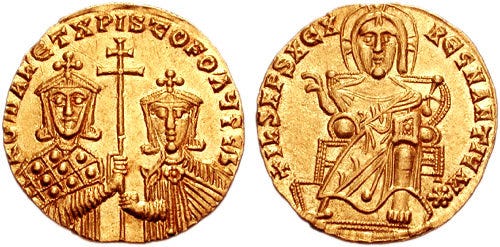

The title of Carlo M. Cipolla’s essay, “The Dollars of the Middle Ages,” refers to the Byzantine solidus, which was also called nomisma by the Greeks and bezant in Western Europe. This Byzantine gold coin functioned as the first true reserve currency throughout a large portion of Eurasia. Cipolla breaks the Middle Ages down into three eras, with three different reserve currency regimes:

In the first period (fifth to seventh century), throughout the Mediterranean—in the rich towns of the Near East, in the markets of North Africa, in the ports of Italy, around the monasteries and the castles of France and of Spain—one coin enjoyed an absolute prestige over the others, the gold solidus of the Byzantine Empire. (p. 15)

Towards the end of the seventh century, Calif Abd al-Malik, perhaps the President Xi of his time, rose to the helm with a project of unification and empire for a young, diverse and heterogenous Islamic civilization. After establishing Arabic as his empire’s language, Abd al-Malik attempted to consolidate his currency system. Previously, as the Islamic caliphate rose in economic power, the inertia of the Byzantine solidus reigned and Arab mints imitated the solidus even down to the Greek inscription of “Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.” Calif Abd al-Malik decided to change the Greek inscription to one in Arabic, “Allah is witness that there is no God but Allah.” and to put his own standing image on his gold coin.

The Arabs were obligated under treaty to send huge numbers of gold coins each year to the Byzantines. Not so unlike the current Chinese predicament of sending vast amounts of manufactured goods to the US in return for so many funny green pieces of paper. In 691, Abd al-Malik sent the coins struck with his image—the Standing Calif coin with Arabic script—to the Eastern Romans in Constantinople. In response, the Byzantine emperor invoked an early case of “suicide sanctions”:

Justinian fell into the trap by refusing the 691 instalment of tribute on the grounds of the new and definitely not Christian image, thereby breaking the treaty and removing Abd al-Malik's embarrassing and debilitating requirement to pay vast quantities of gold to the ideological enemy. Freed from any obligation to pay, and having conquered Iraq in 691 , he could surprise the Romans in 692 by invading Asia Minor and defeating the Roman army at Sebastopolis, all while proclaiming innocence from breaking the treaty.

The Eastern Roman Empire almost collapsed following their defeat but managed to hang on for nearly another 700 years of steady decline. From that point on the Byzantine solidus and Arab dinar shared duty as Eurasia’s reserve currency until the rise of capitalism in northern Italy brought Florence’s fiorino to a position of absolute prestige in the 13th century. In the 15th century, Venice’s gold coin ducato “represented the international currency par excellence.” (p. 21)

With the rise of oceanic naval power in the 15th century, the modern capitalist system allowed for the first truly global reserve currencies:

Since 1450 there have been six major world reserve currency periods. Portugal (1450–1530), Spain (1530–1640), Netherlands (1640–1720), France (1720–1815), Great Britain (1815–1920), and the United States from 1921 to today. If you notice the average currency span is 94 years. The US dollar presently has been the world’s reserve currency for roughly 99 years.

In fact the transition from one reserve currency to another is not as clear cut as the quote above would have us believe. For example the sterling-dollar competition was neck to neck between 1921 and WW2. The transition was only finalised at the Bretton Woods summit in 1944.

Moreover, the idea of a single reserve currency hides the reality of multipolar configurations. In 19th century Europe, there were three separate reserve currency regimes. Britain and her colonies used a gold-based system. Germany and her satellites based their currencies on silver. And a coalition headed by France used a combination of gold and silver known as bimetallism—this bloc included the United States.

As the BRICS+ are further motivated by a desire to escape the dollar zone, as we see there are historic examples were two or more currency regimes reign at once.

Triffin dilemma

This is fundamentally a conflict between a reserve currency’s store of value (gold) and medium of exchange (copper) functions. As Cohen explains in Currency Power:

The earliest warnings came from Triffin in his classic book Gold and the Dollar Crisis. Negotiators at Bretton Woods, he argued, had been too complacent about the gold-exchange standard. In fact, as he sagely pointed out, the regime was fatally flawed because it was based on an illusion—an unquestioned faith that its fiduciary element, the dollar, would always be convertible into gold at a fixed price. The system relied on US deficits to avert a world liquidity shortage. But those deficits, by adding to the swelling total of US liabilities, seemed bound in time to undermine confidence in the greenback’s continued convertibility. In effect, governments were caught on the horns of a dilemma—what came to be known as the Triffin Dilemma. To forestall a flight from the dollar, US deficits would have to cease. But that would confront policy makers with a liquidity problem. To forestall the liquidity problem, US deficits would have to continue. But that would confront policy makers with a confidence problem. The quandary was real. Governments could not have their cake and eat it, too. (p. 163)

At Bretton Woods a decision was made for fixed exchange rates and some US dollar convertibility to gold. This worked for two decades but increasing spending on Vietnam and domestic social programs led to a similar problem that Kublai Khan faced. In 1971, Richard Nixon fighting rising inflation spurred on by the Vietnam war, “closed the gold window”, which meant, in a move similar to Kublai Khan’s, he disallowed foreign governments recycling their excess dollars into gold. This was the moment the US dollar became fiat money.

But the US dollar did not collapse into an inflationary spiral as Khan’s currency did. Once backed by Saudi oil, the petro-dollar became so powerful that manufacturing in the United States became unprofitable. This problem was exasperated as the US gave sweetheart trade deals to the Asian Tigers and to European competitors. In return, these nations promised to continue being faithful anti-communist allies. Deindustrialization followed and the “Rust Belt” emerged. The productivity of manufacturing was replaced by parasitic financialization. The key to US global power in the early 20th century was exactly the same as China’s base of power today: manufacturing and global trade. The dollar’s role as the global reserve currency helped destroy America’s power base.

China doesn’t want the corrupting influence of imperial tribute associated with a reserve currency. Lasting Power is based on economic productivity. Parasitical extractions are corrupting. One benefit of a multipolar currency regime would be to diminish this freeriding activity.

A multipolar gold, silver, and copper reserve currency mix

A global reserve currency also serves the three main functions of money. On the “gold” level, it must act as an international store of value. It must also function as a unit of account, a role traditionally served by silver. And it must provide liquidity for international trade settlement, a role analogous to that served by copper in traditional economies. But in a multipolar currency order, these roles would not be performed by one national currency.

Given that the Chinese economy is the largest manufacturing and trading economy in human history, its yuan could serve a major “copper” role as a primary global medium of exchange, proportional to their economic clout. This wouldn’t mean the yuan is the only medium of trade, just that since China’s economy is the largest, it is natural that its currency would be used for much trade settlement. The highest priority on this level is for the BRICS+ countries to finalize an alterative to the SWIFT payment messaging system.

The primary “gold” reserve currency role could eventually be played by a BRICS+ basket of currencies known as R5+. This name is springs from the coincidence that the currencies of all five BRICS members begins with “r” (real, ruble, rupee, renminbi, rand). The R5+ would also include currencies from oil-rich nations such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the UAE. Given China’s economic strength, the renminbi would have a heavier weight within the basket while a weaker economy like South Africa’s would have a much smaller proportion. The R5+ currency would not replace the BRICS+ national currencies like for example the Euro did. It would act in a similar fashion to the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) device. The BRICS New Development Bank (NDB) is also issuing non-dollar denominating bonds.

While these multilateral institutions are growing, China itself is increasingly acting as the global emergency lender of last resort:

New data shows that China is providing ever more emergency loans to countries, including Turkey, Argentina and Sri Lanka. China has been helping countries that have either geopolitical significance, like a strategic location, or lots of natural resources. Many of them have been borrowing heavily from Beijing for years to pay for infrastructure or other projects.

While China is not yet equal to the I.M.F., it is catching up fast, providing $240 billion of emergency financing in recent years. China gave $40.5 billion in such loans to distressed countries in 2021, according to a new study by American and European experts who drew on statistics from AidData, a research institute at William & Mary, a university in Williamsburg, Va. China provided $10 billion in 2014 and none in 2010.

By comparison, the I.M.F. lent $68.6 billion to countries in financial distress in 2021 — a pace that has stayed fairly steady in recent years except for a jump in 2020, at the start of the pandemic.

Gold may also make a return to the scene to play its traditional role. There are reports of BRICS+ central banks buying gold on the international markets and increasing domestic production. As the Financial Times recently commented:

The anxiety of investors is apt. Gold is the currency of fear and distrust. The financial systems of the democratic west and authoritarian east are pulling apart amid mutual recriminations. That extends the potential role of gold for national reserves and for transactions where no questions need be asked.

As for the “silver” level of a ghost money unit of accounting, the R5+ BRICS+ reserve currency would be the natural choice. Given the increasing overlap between OPEC+ and BRICS+ as Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, and Venezuela seek to join, pricing oil in a R5+ units will send shockwaves throughout the world and give the R5+ unit of account global prestige. A properly conceived multipolar unit of account would facilitate trade between the “copper” currencies of poorer nations without the mediation of a more powerful “gold” currency.

During the 1944 Bretton Woods negotiations, Maynard Keynes presented his Bancor concept as an international unit of account. It would have been ghost money used to price global commodities. National currencies would have a floating relationship to it and gold could be used to purchase Bancors. The Bancor concept’s fundamental goal was to encourage balanced trade. The US delegation rejected this idea in favour of the dollar as a classic reserve currency. Ironically, had the Bancor concept been in use, China would have never been able to build so much economic power based on their huge trade surpluses, and the US would not have been able to run such high deficits. There is little doubt that the US global power position would have been much better today under a Bancor regime.

In 2009, in response to the Global Financial Crisis, Zhou Xiaochuan, the governor of the People’s Bank of China, called Keynes’s Bancor approach `farsighted,´ with Russia, India and Brazil supporting this statement. Although there has been little Bancor discussion since, it will remain an idea on the table in the middle-term if the R5+ device is a success and needs to be expanded to the entire post-dollar globe.

The status of the dollar has rarely appeared high on the American agenda:

Most Americans appear to share the cynical view of John Connally who, shortly after taking office in 1971 as Richard Nixon’s secretary of the treasury, told a group of European finance officials that the dollar “is our currency, but your problem.” (p.166)

But following the China-Russia summit, Americans may soon realize that our dollar is our problem. There will be arguments for and against maintaining US dollar hegemony. Clearly Wall Street has benefitted while working class America has suffered under the weight of dollar power. Any official attempts to resist the dollar’s decline must overcome naïve illusions of power that led to the recent unleashing of suicide sanctions. Actions always provoke counteractions.

All monetary systems must be flexible and so must contain elements of fiat money. The lesson of unipolar systems is that financial hegemons will use this flexibility to their advantage—gold and silver will always look to cheat copper. There is at least a hope with a multipolar system that the “copper” nations may achieve a fair deal with monetary power more widely spread.

Best explanation I have read, also interesting historical background. Worth its weight in gold.. :-)