Quelling the Fire in Ukraine

A look at potential endgames if a Russian victory materializes in Ukraine.

War is like a brushfire—its kindling accrues for decades. Brief smoulders can be extinguished, but once true war blazes, it must burn until the conflictual tinder is spent on one side. This is the point a defeated people must submit to the will of their new master. For the victor, aggression evolves into responsibility and leadership. For the vanquished, belligerence dissipates into obedience. Together these movements mark the dialectical overturning of a fiery state of war into a fresh and hopeful peace.

Peace is never eternal, but it endures at least a few generations after a true defeat. For example, today’s openly bellicose, anti-Russian rhetoric spouted by some German politicians would have been unthinkably just a generation ago. Memories of the Nazi aggression against the Soviet Union, and the Red Army’s subsequent crushing victory, were still fresh in German minds. But time, circumstances and outside interests have encouraged new conflictual kindling to gather under Germany and Russia, increasingly turning German measured restraint into open aggression.

The idea of total peace is as absurd as its contrary, total war. Both are idealistic bookends on an abstract war-peace continuum. Within a zone of peace, there is always some level of tension between two nations or groups. Once lost to the inferno of combat, peace can only be restored after war exhausts the stocks of manpower, armaments and the moral will to fight on the losing side to a level below a social “flashpoint of war.” Determining exactly where this elusive level lies is the work of diplomats, politicians and military strategists. Only after warmaking incinerates one combatant’s means to resist to within range of this flashpoint, can peacemaking begin to quench the remaining embers, opening a path to a zone of reconciliation.

President Xi’s bid for peace in Ukraine

Enormous amounts of war kindling—both psychic and physical—had been stockpiling in Ukraine for decades before an open conflagration ignited. While Chinese President Xi’s recent peace overtures make great PR, they are for the moment disingenuous. There is still far too much war potential remaining in Ukraine for any chance of a lasting peace. In other words, despite the horrific losses, the war there has yet to wear down either side to the flashpoint zone. Rather, Xi’s plan seeks to boost China into the prestigious role of global peacemaker, particularly following China’s recent diplomatic success shepherding Iran and Saudi Arabia towards reconciliation. Peacemaker is a position typically held by the global hegemon. By taking this stance now, China is staking a powerful position for the time when peace does become possible in Ukraine. Plus, the Chinese calls for a ceasefire in Ukraine also play very well to the Global South / Rest of the World.

In some ways an immediate ceasefire could benefit the Collective West as a delay provides time to build an industrial capacity to feed Ukraine’s insatiable shell hunger. But a ceasefire may destroy Ukrainian fighting morale, spawning suspicions of betrayal. Such a ceasefire would not at all serve Russia’s interests because their people would suspect a “Minsk-3” stab-in-the-back sell-out. Sadly the war in Ukraine seems to have many months to go until any thresholds are crossed. Wars of attrition require glacial patience.

The strategist’s cold calculations and emotionless abstractions hide the true horrors of war. In these rational analyses is little space for the agony of parents, spouses, children, siblings and friends of each dead or maimed soldier. But such sorrow does in time amass into the kindling of peace.

War of attrition—inducing plasticity into enemy lines

In On War, Carl Von Clausewitz articulates the purpose of warfare:

I have already said that the aim of warfare is to disarm the enemy <…>. If the enemy is to be coerced you must put him in a situation that is even more unpleasant than the sacrifice you call on him to make. The hardships of that situation must not of course be merely transient-at least not in appearance. Otherwise the enemy would not give in but would wait for things to improve. Any change that might be brought about by continuing hostilities must then, at least in theory, be of a kind to bring the enemy still greater disadvantages. The worst of all conditions in which a belligerent can find himself is to be utterly defenseless. Consequently, if you are to force the enemy, by making war on him, to do your bidding, you must either make him literally defenseless or at least put him in a position that makes this danger probable. (p.77)

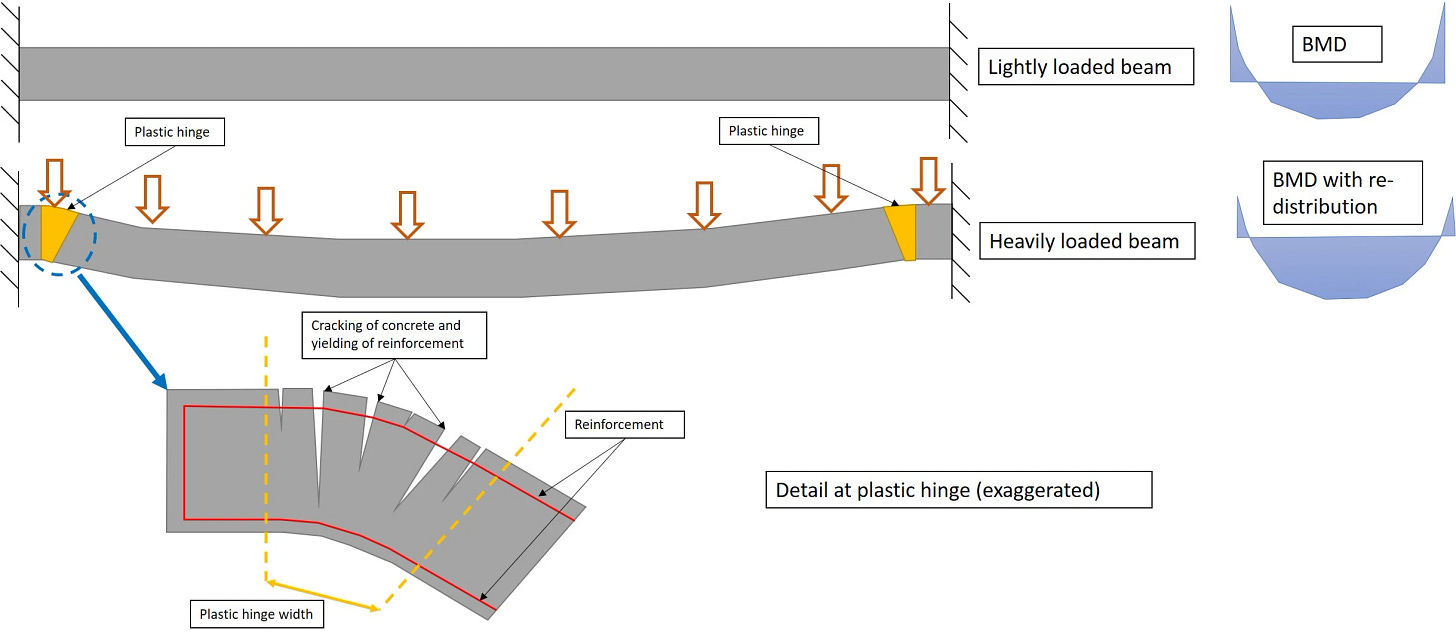

Armies along a front line behave like structural beams. Constant loading on a beam induces small deflections as well as strain and fatigue. Gradually increasing force upon the beam leads to small incremental movements. Eventually though, if enough force is added, the beam will reach the point of plasticity. Catastrophe quickly follows as any additional force produces dangerous bending and eventual collapse. This is Russia’s goal in Ukraine, to induce the Ukrainian armed forces into a state of plasticity where Ukraine will either be forced to sue for peace or watch their armies collapse allowing the Russians free reign to occupy any areas they wish.

Reducing your opponent to the point of plasticity means destroying their manpower, armaments, and fighting spirit. In wars between asymmetrically sized nations, the country with the smaller population must generate a higher kill ratio. With Russia having a population roughly five times that of Ukraine, a simple calculation shows Ukraine must achieve a 5:1 kill ratio to make their war effort sustainable. If the opposite were true, if five Ukrainians are dying for each Russian, then over time the war is untenable.

Many analysts see Russia’s modest territorial gains as a sign it is losing. However in a war of attrition, if capturing and holding vast areas of land mars an army’s kill ratio, such moves can lead to defeat. The objective is to hold strong positions which maximize enemy deaths while sparing your own fighter’s lives. The strategic defensive is the ideal configuration. Historically Russian armies have retreated and traded land for attrition. In Ukraine both the Kharkov and Kherson retreats by Russia changed the battlefield to ensure better kill ratios for Russian forces.

This means Russian offensives are effective—not if they take land—but if they induce Ukrainians into high-casualty inducing defensive stands, as seems to be the case in Bakhmut. Given the fog of war, nothing is certain, but there are many reports of high Ukrainian casualties coming out of Bakhmut. While NATO sources dutifully claim that Ukraine does indeed maintain the requisite 5:1 kill ratio, other Western sources announce 100,000 Ukrainian deaths against 60,000 Russian deaths. Other sources place the Ukrainian death toll much higher. S.L. Kanthan recently posted on Twitter troubling excerpts from a Washington Post, an article he argues is meant to prepare Western audiences for a defeat in Ukraine:

Media reports during wartime must be regarded as sceptically as TV commercials. What Dorothy Parker claimed about advertising holds true for war reporting as well:

Of course, there is some truth in advertising. There’s yeast in bread, but you can’t make bread with yeast alone. Truth in advertising … is like leaven, which a woman hid in three measures of meal. It provides a suitable quantity of gas, with which to blow out a mass of crude misrepresentation into a form that the public can swallow.

Given these precautions, there has recently been a remarkable shift in narrative-intent within Western war reporting. The exuberant optimism of the Ghost of Kiev-era is replaced by much darker reporting from the front about the Russians “tasting victory.”

Three endgame models

But what would an end to hostilities look like if Ukrainian forces approach plasticity? It’s a mistake to conclude that in the worst-case, Ukraine can call some sort of time-out and freeze the conflict on its current lines. Such agreements are possible, but it is unlikely that Russia would be interested. The stakes are much higher. Depending on how negotiations end, suing for peace can entail losing your entire nation. It’s crucial for leaders facing defeat to conclude a peace deal before passing beyond the point of plasticity. The complete collapse of armies destroys any leverage in negotiations. On the other hand, suing for peace too early, before a population has been properly prepared for defeat, beckons “stab-in-the-back” legends where war continues to smoulder within a disgruntled segment of the population, and can then reignite in the next generation.

Germany in 1918

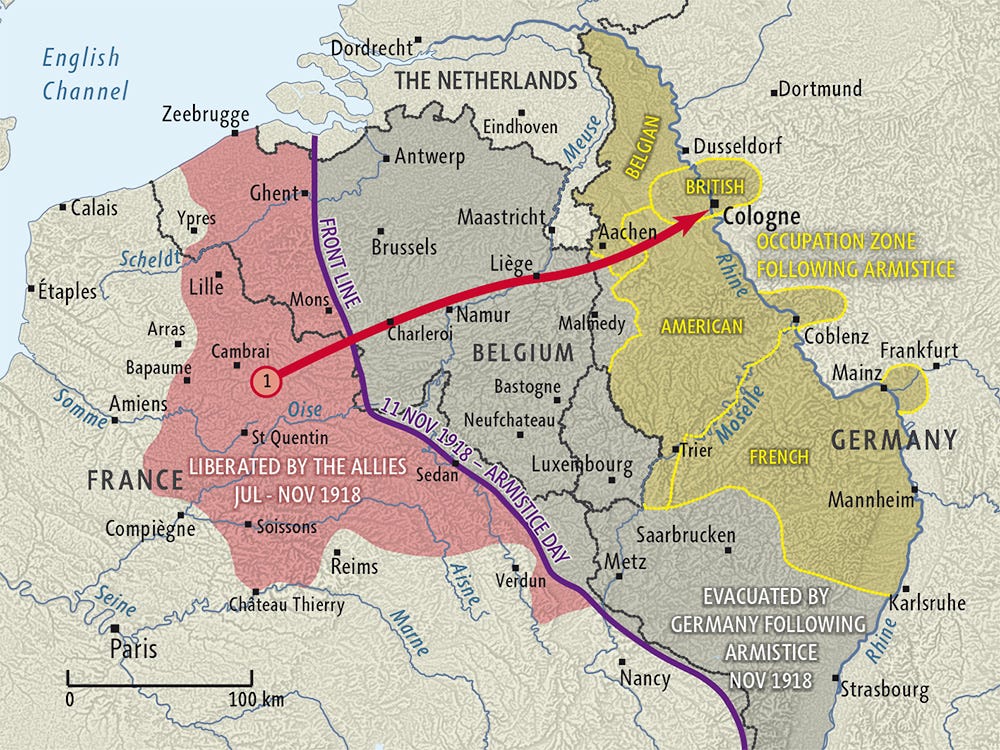

Despite being fought by far fewer soldiers, the Ukraine War has settled into a WW1-style war of attrition fought along a front with only relatively small territorial movements. In the spring of 1918, high on optimism following their crushing victory over Russia in the east, Germany launched a Spring Offensive and managed to capture what in WW1 were considered impressive amounts of territory in a last desperate attempt at victory for the exhausted nation. But the price in manpower and armament was too high. These tactical victories pushed Germany ever closer to strategic plasticity and collapse.

In late summer of 1918, the nearly equally exhausted Allies launched their own counter-offensive and managed to capture relatively impressive amounts of land (red zone in map above). At this point the alarm bells went off within the German general staff as they realized their armies had reached the dangerous point of plasticity. The generals instructed their political leaders to sue for peace. The resulting armistice forced Germany to both withdraw from occupied lands (grey zone) and even surrender German territory behind the Rhine (yellow zone). A defeated Germany meekly agreed to demobilize, turn over weapons and materiel, all while sanctions were maintained during the subsequent peace treaty negotiations.

If the Russian army were to suddenly collapse, this model would apply very well to the terms of a Ukrainian victory. However, current trends seem to show Ukraine approaching the point of plasticity much faster than Russia. What this example demonstrates is that Russia does not have to capture vast amounts of territory during the war in order to control it afterwards. What counts is fighting in a way that pushes the opponent towards plasticity while avoiding such a fate for your own army. In a war of attrition, only once the opposing army is broken can opportunistic land grabs begin.

Japan in 1945

Another possible blueprint for a victorious Russia to follow is the US occupation of Japan in WW2. During the war, the US never held a square inch of Japan’s home islands. But after Japan’s capitulation, the US occupied the entire nation with the exception of a couple islands the Soviet Union managed to capture in the closing days of the war. Once in power, the US proceeded to rewrite the Japanese constitution ensuring that Japan would many generations not pose a threat to the US. Only in 1952 did a pacified Japan regain sovereignty.

After their victory, the US kept Japanese Emperor Hirohito in place as a useful figure head. In Ukraine, the West has invested heavily in PR campaigns during the past year painting Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky as the global shining knight of democracy. If during occupation, Russia can flip Zelensky into a ceremonial puppet role, like the US did to the Japanese Emperor after WW2, it would represent a huge win for Russia. Just as the US accomplished in Japan, the long-term goal for Russia is to flip Ukraine from a potential threat into an enduring, obedient and faithful ally

However, Japan required a massive occupation with more than one million American soldiers taking part, reinforced by hundreds of thousands of additional allied troops. Russia may not have the capacity or desire for a huge occupation of Ukraine after any hypothetical defeat.

France in 1940

If Ukraine and WW1 are examples of slow boring wars of attrition, WW2 was a fast war of manoeuvre which featured exciting big arrow offensives and blitzkrieg penetrations. In one of the most spectacular military victories in the history of mankind, Germany between May 9th and June 22nd utterly destroyed the French army. After the breakthrough at Sedan and then the crossing of the Maginot line, the French army crumbled and quickly sought an armistice.

France was divided into three main types of zones. Alsace-Lorraine, while not officially annexed, were under strict German control. These areas have some resemblance to the Donbass as an culturally ambiguous borderland. The yellow zone was German occupied while the blue zone represented Vichy France, a nominally independent France but under the control of a German-aligned puppet government. Of special interest is the red coast zone, which was a special military area where Germany constructed their Atlantic Wall defence chain.

Potential Russian gains in Ukraine

In the event of victory, Russia may well be tempted to create a “Vichy” Ukraine in the blue zone of the Big Serge Annexation Map, run by a government sympathetic to Moscow. But a protection zone on the Polish and Romanian borders will be critical for keeping out NATO supplies away from any eventual insurgencies that form. The yellow and orange zones may be occupied by Russia and then danged as bait to be returned to a future well-behaved and Russian-allied Ukraine. The red zone will likely be annexed directly by Russia.

Ukrainian soldiers have proven their bravery and fighting skill. The survivors along their martial traditions and spirit could be incorporated into future Russian armies just as the Chechens were following their defeat to Russia.

Today Ukraine can no longer gently slow-dance with Russia in a grisly war of attrition. Under intense Western pressure to “show results,” Ukraine must now launch big arrow offensives. Only a spectacular breakthrough of Russian lines, similar to those in 1940 France, will reverse the current negative Ukrainian trendlines in manpower, armaments, and fighting morale. Failure will push Ukraine dangerously close to the flashpoint level where a lack of war kindling makes fanning enough flames to prosecute a war impossible.

For Russia, visions of an exposed charging opponent, naked of fortress, is the stuff their strategists dreams are made of. Will Russia’s glowing coal embers style of attrition war prevail over the onslaught of a Ukrainian firestorm? The coming months will tell.