Moving Home: Roots, Routes and Ruins

An introductory essay to a series on Zionism's five main ideological currents and their legacy for modern debates on belonging, migration and estrangement.

To survey Jewish history is to confront a persistent oscillation between catastrophe and triumph, between the effort to transform adversity into vitality and the recurrence of destruction that echoes through the ages. From the bondage of Egypt to the conquest and settlement of the Promised Land, the narrative registers both human agency and divine orchestration: the jubilation of arrival is commemorated in sacred space, yet the threat of annihilation looms always on the horizon.

The First Temple, built by Solomon, symbolized a moment of national consolidation, a locus of triumphal identity, while its destruction by the Babylonians became a paradigmatic catastrophe, etched into collective memory. Yet even in exile, catastrophe gave rise to renewal: in Babylon, the Jewish people began to reorganize their religious, social, and legal structures, laying the foundations for much of later Judaism. The exile demonstrates the persistent cycle of disaster and consolidation, where the loss of homeland and temple paradoxically became a crucible for communal and spiritual creativity.

The Second Temple period, beginning with its construction under Zerubbabel with Persian support and later expansion by the client-king Herod the Great, witnessed a renewal of Jewish life in Judea—a renewal increasingly darkened by the shadow of Roman imperial power. This tense equilibrium shattered in 70 AD, when the destruction of the Temple by the Romans—archetypal imperial authority, embodied in the figure of Caesar—marked a profound rupture in Jewish life. The subsequent, heroic but doomed stand at Masada served not as a parallel event, but as its tragic coda: where the Romans represented overwhelming external force, Masada became a symbol of defiant Jewish agency, even in total defeat. Echoes of this ancient last stand reverberate through Gaza today.

In the aftermath of this catastrophe, a new liturgical and theological framework emerged, interpreting the disaster as divine judgment. As the Talmud (Yoma 9b) explains, the Temple was destroyed primarily because of sinat chinam—“baseless hatred” between Jews themselves. This internal strife was seen as a spiritual failure so grave it invited divine punishment in the form of Roman conquest. This theology became the core of the exilic creed: Jews were expelled from the Land of Israel for their own sins, and their return was to await the coming of the Messiah—a hope deferred, yet persistent, recited annually at the Passover Seder: “Next year in Jerusalem.”

Zionism, in this light, can be read as the most modern chapter in an ancient cycle: a deliberate and political act of moving home. The phrase itself carries a layered resonance. In Britain, the more common expression is moving house—a pragmatic description of the logistics of relocation, packing boxes and resettling elsewhere. Yet the British usage moving home exists alongside it, inflected with greater emotional weight: the attempt to establish or re-establish a dwelling. In American English, meanwhile, moving home typically suggests a return to one’s origins, to a familiar or ancestral place. Zionism draws power from both registers. It was at once a colossal logistical undertaking—settlement, infrastructure, sovereignty—and a mythic act of return, a homecoming framed against centuries of exile. In this doubleness, Zionism exemplifies the wider human struggle for rootedness: the tension between the material act of relocation and the existential yearning to belong.

The Palestinians, likewise, are caught in this relentless movement: displaced by the Zionist project and forced into involuntarily moving home in the British sense — relocating amidst destruction and blockade — while simultaneously clinging to the idea of their lands and communities, always dreaming of a return, of a moving home in the American sense.

Zionism, in its successful realization, transforms recurring vulnerability into sovereign self-determination, yet remains inescapably conscious of the shadows cast by past catastrophes suffered in defeat, from Babylon to Rome. But Jewish sovereignty has also left catastrophes in its wake: the Nakba of 1948 and the ongoing devastation in Gaza, where another people’s exile is bound up with Israel’s survival. Whether triumph was celebrated in a Temple or mourned in dispersion, the rhythm of calamity and resilience has continually shaped Jewish existence — and, more broadly, underscores the universal human negotiation between home and homelessness.

The question of “homeland” — or more profoundly, the German concept of Heimat, implying a deep, almost mystical belonging to a particular soil, culture, and community — has always haunted Jewish existence. Centuries of exile, ritualized in prayers for return, produced not only a spiritual yearning but also a social condition of homelessness (Heimatlosigkeit), where communal cohesion was as much a defense against rootlessness as against persecution. It was this very European ideal of Heimat that became a potent weapon against Jews: the 19th-century German Romantic vision defined belonging in exclusive ethnic, cultural, and territorial terms, thereby casting Jews as eternal outsiders, incapable of true rootedness. Yet, in a profound paradox, the ghettos and shtetls that embodied this exclusion also served as fragile, functional forms of Heimat. Though imposed and often humiliating, they offered bounded spaces where Jewish ritual, language, and community could persist in a state of relative autonomy.

Emancipation disrupted this equilibrium. It promised liberation from confinement, but it also dissolved the protective walls of the ghetto, exposing Jews to the demands and pressures of assimilation. What had been an enforced Heimat, however limited, gave way to the precarious task of negotiating belonging in a wider gentile society that continued to regard Jews as alien. The newfound freedom was thus double-edged: it granted access but intensified vulnerability, dissolving one form of cohesion without securing another.

Zionism emerged as one response to this predicament. In place of the vanished ghetto, it sought to create a new and deliberate Heimat, grounded not in imposed segregation but in sovereign self-determination. If the ghettos had been an involuntary home, Zionism imagined a chosen one: a collective project to transform centuries of exile and displacement into a national framework of belonging. Yet in doing so, it carried forward the paradox of Jewish history: the attempt to solve homelessness through the construction of home, while simultaneously producing new forms of exclusion for others.

This paradox points toward a broader, universal condition: the uncanny space between Heimat and Heimatlosigkeit, where belonging is precarious, provisional, and never secure. In Mandate Palestine, both Jews and Palestinians inhabited this liminal zone: Jews claiming a homecoming yet marked as newcomers, Palestinians rooted in the land yet increasingly unsettled by the slow erosion of their security. Here, the questions of colonialism and immigration converged. The very drama of “return” was also the drama of intrusion, forcing both peoples into the unstable middle ground between home and homelessness.

That same instability reverberates into Europe today, where the influx of migrants unsettles the fragile balance of identity and belonging, inverting the roles of figure and ground: once the colonizer, Europe now experiences itself as the site of contested Heimat, a stage where migration, memory, and fear collide. From the migrants’ perspective, the rupture is even sharper: leaving societies embedded in long civilizational continuities, they arrive in a postmodern Europe where—as Marx once wrote of the relentless churn of capitalism—“all that is solid melts into air.” For those from societies often defined by deep, if sometimes oppressive, continuities, this experience is one of radical disorientation: the very semblance of order evaporates into flux.

Proto-Zionism: Krochmal’s Hegelian Idealism

Nachman Krochmal was born in 1785 in Brody, a Galician town on the unstable borderlands of empires—a man shaped by a world where the very idea of Heimat was fragile and contested. Galicia was the quintessential unstable homeland: administered from Vienna but haunted by Polish memories of lost sovereignty, peopled by Ruthenians (later known as Ukrainians) nursing their own national aspirations, and dotted with Jewish shtetls that embodied a precarious, almost metaphysical rootedness—a sense of place utterly divorced from political power. Sovereigns moved across the region, borders shifted, and various groups sought to make Galicia their home. In this crucible of unstable belonging, Jewish communities learned that moving home was not just physical, but social and spiritual, negotiating identity amidst impermanence.

Out of this environment emerged the first systematic philosophy of Jewish history. Krochmal’s Moreh Nevukhei ha-Zeman (“Guide for the Perplexed of the Time”), published posthumously in 1851, attempted for the Jews what Hegel had performed for Europe: to discern a rational pattern in the convulsions of history and to provide a framework for future regeneration. If Galicia revealed Heimat as a perpetually unsettled condition, Krochmal’s project foreshadowed a movement—later Zionism—that would seek to stabilize Jewish existence once and for all, transforming cohesion from a reactive effect of exile into the conscious project of a people.

For Krochmal, the glue of Jewish continuity had always been external oppression: in the absence of sovereignty, persecution acted as the centripetal force holding the people together. But this was, in his eyes, a negative, mechanical bond—an artefact of historical necessity, not inner vitality. The Enlightenment opened a new horizon: Jewish cohesion could be reborn not through reaction to hatred from without but through a conscious, philosophical grasp of Jewish destiny. In this, Krochmal was an idealist.

Half a century later, Theodor Herzl (1860–1904), the founding father of modern Zionism, confronted this same problem in a radically different historical context. Born in Budapest and working as a journalist in Vienna and Paris during the Dreyfus affair, Herzl witnessed anti-Semitism as a virulent, inescapable reality. Where Krochmal sought to transcend coercion through consciousness, Herzl insisted that external hostility could not be philosophically dissolved but must instead be harnessed. “The anti-Semites will become our most dependable friends,” he wrote in his diaries; “the anti-Semitic countries our allies.” For Herzl, persecution was not a problem to be solved abstractly but a lever to achieve sovereign Jewish self-determination—a very concrete form of moving home, asserting stability in a world that had persistently denied it.

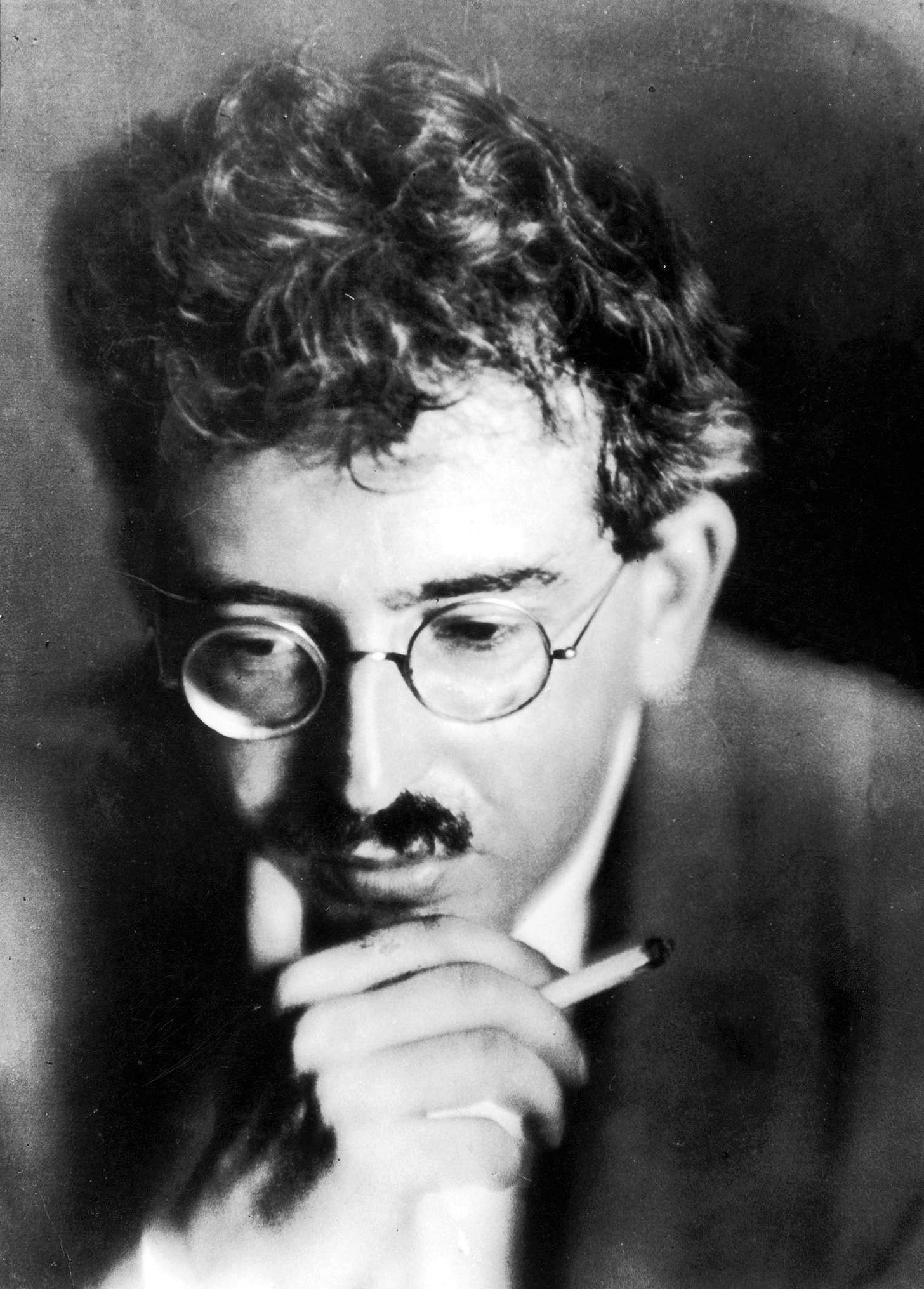

Benjamin’s Philosophy of Catastrophe

Walter Benjamin, writing in the first half of the twentieth century, approached history from a profoundly different angle. Where Krochmal discerned a dialectical ascent and Herzl saw opportunity in adversity, Benjamin perceived catastrophe as the persistent, unrelenting condition of human affairs. History, for him, was not the unfolding of Spirit or the teleology of progress, but a landscape of wreckage: “a storm blowing from Paradise” that drives humanity forward while the debris of the past accumulates endlessly at our feet. Each epoch leaves its ruins, each triumph conceals catastrophe, and every act of construction is haunted by what has already collapsed.

Benjamin’s method becomes startlingly tangible in the present. One need look no further than Gaza: nearly two million souls inhabit a densely packed, largely underground world, surviving amid landscapes of flattened homes and shattered infrastructure—the unmistakable debris of contemporary catastrophe. Here, home is more than four walls and running water; it is the claim to presence itself, the refusal to accept homelessness, to be cast permanently as wanderers or exiles. This steadfast refusal to be displaced—this human insistence on claiming home despite overwhelming force—ensures, in Benjamin’s stark terms, the endless accumulation of ruins. It is a tragic dynamic that imposes an unavoidable ethical weight on every future reconstruction built atop today’s devastation.

The immediacy of catastrophe is further amplified when Tel Aviv enters the frame. During the recent Twelve Day War, Iranian ballistic missiles struck residential neighbourhoods, reducing apartments to rubble and spreading terror—though on a scale miniscule compared to the devastation in Gaza. Yet this asymmetry itself is deceptive; it plants a ruinous seed, a hint that the historical cycle of destruction may be rebounding, its logic now accelerated to a terrifying pulse. Where ancient rhythms of conquest and exile—from Babylon to Masada—unfolded over centuries, modern violence compresses them into days.

This is the fatal acceleration of war that Paul Virilio diagnosed: technological ‘progress’ that shrinks time and space to deliver ruin instantaneously. The languid rhythm of history has been shattered; triumph and ruin are now simultaneous events, and the fragile human Heimat is perpetually imperilled. It evokes Adorno’s grim observation on the dialectic of progress: that humanity’s journey from the slingshot to the megaton bomb is one of technological perfection coupled with moral atrophy—a progression that now echoes in the Middle East’s escalating exchange of fire.

It is in this tragic register that Benjamin illuminates the tension at the heart of Zionism. Krochmal offered a vision of catastrophe sublimated into vitality, a pathway through which adversity could be transformed into a consciously chosen Heimat of the spirit. Benjamin, by contrast, insists on the ruins, the debris, the impossibility of full reconciliation: catastrophe must be confronted, remembered, and acknowledged. Zionism, in the modern state, exists in this interstitial space: it aspires to a stable and enduring Heimat, yet it is perpetually marked by the recurrence of violence, the weight of historical rubble, and the ethical entanglement of building home atop displacement.

The oscillation between Krochmal’s idealist horizon and Benjamin’s tragic awareness is the lens through which not only Jewish political and cultural life but human history more broadly must be read. Today’s drama in Gaza will, in one form or another, be replayed across the crumbling industrial cities of Europe, where the struggle for Heimat endures. It is the human fate of a compulsively migratory species that values nothing more than rootedness, yet is perpetually confronted by displacement, ruin, and the relentless return of catastrophe.

The Architectures of Answer: Four Paths from the Ghetto's Shadow

The opening of European society in the nineteenth century presented Jews with both opportunity and crisis — a paradox heightened by the simultaneous rise of European nationalism. While emancipation dissolved the protective walls of ghettos and opened civic and social avenues, the newly consolidated nation-states were increasingly defining belonging in ethnic and cultural terms, leaving Jews in a double bind: granted rights as citizens, yet persistently marked as outsiders. This collision of sudden freedom with constricting social boundaries produced a spectrum of competing, and often mutually hostile, strategies for negotiating catastrophe, cohesion, and Heimat — the precarious sense of home and belonging. Four archetypal responses emerged: assimilation, psychoanalytic reflection, revolutionary transformation, and nationalist political pragmatism. Each sought to reconcile the pressures of history and modernity with the desire for stability, recognition, and agency in a world that could turn catastrophic at any moment.

Assimilation: The Strategy of Social Integration:

Assimilation represented the attempt to secure Heimat through full integration into European society. Jews who pursued this path, from the followers of Moses Mendelssohn in Berlin to the champions of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment), sought to minimize difference, blending into dominant cultural norms. Reform Judaism, whether in Germany or later in the United States, attempted to reframe Jewish identity into a socially legible "religion" analogous to Protestantism, often shedding national and linguistic particularities. Yet the experience was fraught with tension: the Jewish parvenu, admired for achievement and sophistication, could quickly become the pariah, marked as other when social or nationalist anxieties intensified. Stability, recognition, and belonging were therefore always provisional; catastrophe could strike in an instant, revealing the fragility of a Heimat dependent on external approval rather than autonomous cohesion.

Freud: The Strategy of Psychological Universalization:

Sigmund Freud offered a distinctive strategy for navigating the double bind of emancipation and exclusion. He reframed Jewish particularities — psychic conflicts, neuroses, and cultural traits — as expressions of universal human conditions. In works like Civilization and Its Discontents, the pressures of modern life and the disruptions of social integration were not uniquely Jewish; they were symptoms of the human condition writ large. Heimat, in Freud’s schema, is internal and psychological: coherence of the self, a stable psychic domain amid the turbulence of history and society. Catastrophe becomes a shared, existential challenge, and survival is enacted through understanding and integrating these psychic pressures rather than through territory or politics.

Marx: The Strategy of Political Transcendence:

Karl Marx approached Jewish identity through the lens of historical materialism. In On the Jewish Question, he made his notorious argument: the practical, worldly spirit of the Jew had become the foundational principle of bourgeois civil society itself. What had been a specific Jewish relationship to money and contract was now the universal logic of capitalism. Therefore, the "social emancipation of the Jew" meant the emancipation of society from capitalism itself. The solution, for Marx, was radical: to transcend the very categories of "Jew" and "Christian" through revolutionary class struggle. Catastrophe is systemic, and Heimat is reconceived at the level of social structure: belonging is not secured through culture or territory but through the transformation of society itself.

Herzl/Zionism: The Strategy of Political Realism

Theodor Herzl’s response was pragmatic and territorial—a direct refutation of Krochmal's philosophical idealism and a embrace of raw agency. Confronted with persistent exclusion, he sought to convert Jewish vulnerability into sovereignty, creating a tangible Heimat through statehood. Political realism guided his strategy: anti-Semitism could be leveraged as a tool if European powers saw a Jewish homeland as serving their interests. Jews, through political and military organization, could assert themselves as a normal people, fully sovereign and capable of defending their space in the world.

Zionism in the Storm of History

Zionism was never a monolith; it was and remains a battlefield. The same historic pressures that produced the four archetypal Jewish responses to emancipation—assimilation, psychoanalysis, revolution, and Zionism—crystallized within the Zionist project itself and branched into five competing currents, each claiming the one true path to a Jewish Heimat.

This series on Zionism will dissect these five tendencies:

Political Zionism (Herzl): The diplomacy of desperation, pursuing a charter for statehood by leveraging the rivalries of empires, a modern echo of the court Jew's precarious art.

Labour Zionism (Ben-Gurion): Socialism with Jewish characteristics to create a new Jew and a just society, forged through sweat, soil, and the exclusivity of Hebrew labour

Revisionist Zionism (Jabotinsky): An iron-wall doctrine of Hebrew honour, military strength, and unapologetic sovereignty, underpinned by a fascist-corporatist model that dissolved class struggle into national glory.

Cultural Zionism (Ahad Ha'am): The spiritual centre, fearing a people without a soul, winning the diaspora through cultural hegemony rather than political conquest of the Palestinians.

Religious Zionism (Kook): The mystical belief that human political agency—the act of building a state—is a sacred catalyst for divine redemption, its first flowering.

We will trace these currents from their origins in the diaspora, through the battles of Mandatory Palestine over immigration and land, to the Palestinian catastrophe of the Nakba and the founding of the State of Israel. This is not merely history. It is the key to understanding the fierce internal conflicts that define Israel today—and the uncanny echoes of these struggles in contemporary Europe’s battles over migration, home, and belonging. The central question is no longer just what Zionism was, but which of its competing visions will ultimately prevail. And as Europe and its newcomers slide toward confrontation, as indigenous majorities trend towards minority status, each may yet find themselves unconsciously replaying the strategic precedents first forged in the Zionist-Palestinian crucible.

Dear Kevin,

Three questions:

1. The Second Temple. You referred to Persian encouragement. Are you referring to Cyrus the Great’s liberation of the Jews from the Babylonians?

2. What current does the government of Bibi Netanyahu represent?

3. You wrote that Herzel used Zionism as a lever to obtain colonial Europe’s assent to a Jewish homeland? What did you mean by that? One could think of two interpretations:

3.1. To get rid of the Jews in Europe by encouraging their “emigration”

3.2. To use the Jews of Europe as permanent outposts of Europe on Muslim land?

3.3. Could one attempt to frame the current crisis in Palestine as the latest episode of the Crusades?

I am quite interested in more deeply understanding the issues here.

My final thought is that, although I support Israel’s right to exist as a sovereign nation-state, I fear that the two-state solution will not work. Over a few decades, the two peoples occupying Palestine-Israel will be forced to cohabitate and be one state with two nations. A forced conjoint twins. A deformed political entity but inevitable by the forces of history. Belgium is a more pleasant face (the Walloons and the Flemish nations).

In the end, neither Jews nor Palestinians can vanquish each other, and the ferocious reaction of the Israeli state in Qazza will debase the Jewish holocaust and “engender” a Palestinian one!

With apologies to anyone who might object to my views but as a human being, I can only make sense of this living Hello for both nations through my own read of history and the formation of holy national narratives.