Killing Kirk

Fighting father figures in an Age of Despair: Charlie Kirk, Nick Fuentes, and the struggle between boomer authority, Zoomer rebellion, and the temptation to forge new values in American politics.

With political figures, I tend to have what might be called an avoidant attachment style: I remain largely emotionally uninvested, neither loving nor hating them, though I come closest to breaking that rule with figures like Lindsey Graham or Victoria Nuland. My attachments, instead, follow what I think of as concentric circles of empathy: first toward my own family, then outward to those who resemble them, and ultimately to humanity at large. Yet the innermost, most visceral circle is reserved for the young. It is this empathy that constricts my heart when I witness boys dying—boys who could be my sons—in the relentless slaughter of Ukraine and Gaza, where children perish in staggering numbers every day.

Charlie Kirk was a father of two young children. I know through close friends the lifelong anguish of growing up fatherless—a pain his own children will now face. Yet my most immediate reaction to the assassination was not to his death, but to the sight of an older man being arrested (mistakenly it turned out) for the crime. The image of the old harming the young recalled the grotesque inversion of natural order I witnessed during the Covid years, when risk was systematically pushed downward onto the young for the benefit of the old. In these moments, society contorts the concentric circles of duty and empathy: instead of nurturing the young as carriers of the future, it sacrifices them upon an altar of affluence and its concomitant disorder.

Yahweh, Satan, Job and His Wife

As someone generally uninvested in the two establishment parties, I was nonetheless aware of Charlie Kirk—primarily as the nemesis of Nick Fuentes, two forces vying to corral today’s right-wing youth. What struck me most about Kirk was how anachronistic he seemed: essentially a millennial Mitt Romney, tasked with marketing his political fathers’ failing boomer conservatism to its primary victims—the despairing Zoomer generation (born 1995–2010), confronting unprecedented economic and social pressures.

This generational tension deepens when refracted through myth. In the Book of Job, Yahweh and Satan lounge together in heaven, sharing an eerily cordial conversation about the faith of a single earthbound man. Yahweh extols Job’s integrity; Satan cynically suggests it’s merely the fruit of privilege. Their bet resolved, Job is stripped of comfort, family, and fortune. In the nadir of suffering, Job’s wife reactively urges him to curse the very deity they both once revered.

Fuentes assumes the role of Job’s wife in the political realm, tempting his cohort to break from reverence. He is the Zoomer Francisco Franco: Catholic, strident, nationalist, rhetorically symbolizing the return of yesterday’s hard men. While Kirk urges his audiences to “stay the course” and endure, Fuentes pushes for transgression—profaning the icons of today: Jews, blacks, women, even the Trump administration. It is this last target that brought him into the mainstream eye; there is no critic of Trump more devastating than Fuentes, which paradoxically is why major outlets have platformed him.

Kirk’s political “fathers” are tangible, anchored in the boomer establishment and the machinery of governance, demanding that he subsume his interests to the reigning order. The “Israel Question,” for example, exposed the gut-wrenching tension between his personal inclinations and the expectations of power. Fuentes, by contrast, is unburdened by living patriarchs—his “fathers” are spectral, the fascist ghosts of generations past, granting him rhetorical and imaginative freedom.

This dynamic mirrors psychoanalytic insight: hatred and aspiration displaced onto surrogate father figures—a classic ego-ideal transfer. Two archetypes emerge: the resented, reactive father as locus of grievance, and the aspirational, idealized father as site of creative emulation.

What was once latent in Fuentes’s rhetoric emerges in recent Zoomer doubts about whether the “right side” even won the Second World War, invoking General Patton’s controversial suggestion that the U.S. may have fought the wrong enemy. The despair fuelling these doubts is rooted in real precarity. As Fuentes puts it: “Debt slavery. Never owning a house, never owning a car, never paying off their school. Never making an income to support a family. Not being able to have a family.” Who really did win World War 2?

Fuentes’s program might be called a reactive re-filiation, a fantasy in which the Greatest Generation would have chosen fascist cohesion over liberal-capitalist dissolution. Dubious as it is, the example of Communist China shows how a disciplined, homogenous, hierarchical state can achieve what fascist America might have dreamed.

Plutarch, in his Parallel Lives, anticipated modern theory: true understanding arises not from binaries but from the productive power of relation. He paired Caesar with Alexander for contrast, not opposition. Kirk and Fuentes, too, are not fixed adversaries but generative dyads—mutual shapers whose interplay produces pressures, meanings, and outcomes neither could secure alone.

The Browning of White Supremacy

Dealing with the Zoomer world is challenging for us oldsters because their language is highly creative, ironic, and layered. If Rush Limbaugh had his Dittoheads, Nick Fuentes commands his own angry army: the Groypers.

The origin of the term “Groyper” remains unclear and elusive—a fitting reflection of the playful ambiguity central to Zoomer meme culture. First attested around 2015, the name is closely tied to a rotund, contemplative frog image, various hypotheses about the word’s roots circulate: some suggest a blend of “goy” (a non-Jew or Gentile) and “griper” (a habitual complainer); others propose a play on “grope” or an onomatopoeic nod to a toad’s croak. Yet none commands consensus, and the term’s meaning remains fluid and multi-layered—resisting fixed interpretation while embodying the movement’s ethos of boundary-testing through irony and coded language—the height of postmodernism.

The movement gained notoriety in the so-called “Groyper Wars” of 2019, when Fuentes’s followers confronted Charlie Kirk at Turning Point USA events, ambushing panels with loaded questions on Israel, immigration, and cultural issues. For these young dissidents, a “Groyper” became a Gentile challenger, someone who would confront the Zionist-friendly right from an implicitly America First perspective.

Against the backdrop of the ongoing slaughter in Gaza and near-uniform Republican support for Israel, with Democrats muted and hesitant, many young people desperate for critique have found their clarion in Fuentes. This is the double bind: to support the most scathing critic of Israel and its bipartisan American enablers means embracing a provocateur with open fascist tendencies.

Fuentes himself—an ethnic amalgam of Mexican, Italian, and Irish ancestry—is as magnetic at the microphone as he is ideologically transgressive. The establishment media, drawn to the spectacle and the fractures he exposes, recently granted him and the Groypers space in The New York Times and The Atlantic. Their interest: the insurrection on the right led by Fuentes, including his threats to turn his movement toward Gavin Newsom in 2028. With trademark provocation, he praises the all-American whiteness of Newsom’s family—an almost parodic jab at both Republican performative multiculturalism and Democratic racial neuroticism. On JD Vance he delivers another: “You can’t make me go and vote for some fatass with a mixed-race family.” Trolling is both method and message.

In one remarkable monologue, Fuentes transgressed both partisan lines and racial taboos, when he brutally chastised Stephen Miller, a Jewish immigration hawk who currently serves as the White House deputy chief of staff. When Stephen Miller insulted “white liberal women,” Fuentes rejected any right wing partisan alliance with Miller, and instead claimed a more primal racial filiation with left wing women. He threw down a racial gauntlet, bluntly inviting Miller to move back to Israel if he could not accept all political shades of the racial founders of America, defending the ideal of whiteness before any partisan loyalty.

The Atlantic article, published prior to Kirk’s murder, highlighted the divergent approaches Fuentes and Kirk took toward Trump:

In June, many MAGA figures adjusted their positions after Trump attacked Iran. At the time, Charlie Kirk wrote on Facebook that he was open to America supporting regime change in Iran; a few months earlier, he’d posted on X that, under Trump, “America has a golden opportunity to pull away from Middle East quagmires for good.” By contrast, Fuentes criticized Trump directly: “So delicious watching people defend Trump for the past week because ‘he isn’t doing regime change,’ only for him to immediately start advocating regime change the day after bombing Iran,” he wrote on X.

When the Trump administration refused to release the Jeffrey Epstein files, many pro-Trump figures were unhappy but did not directly attack the president. “I’m going to trust my friends in the government to do what needs to be done,” Kirk said at the time. Fuentes took a different approach: “Let us never forget that one year ago today, our President Donald Trump was spared from sudden death by God,” he posted on X. “Trump took a bullet so that he could live to cover up Epstein’s pedophile island and to bomb Iran for Israel.”

This puts the liberal establishment in a paradoxical bind. Fuentes is the most effective critic of Trump’s administration and America’s ongoing support for devastation in Gaza—yet his own ideological values are odious to the mainstream. Do they platform him as he eviscerates the right, or recoil from a man committed to upending every norm of dialogue? By labelling him a white supremacist, their articles serve as a kind of performative hygiene measure, simultaneously condemning and legitimating his rebellion on the right.

The deepest irony is that Fuentes and much of his movement are, at best, “off-white” or often outright mixed-race. Many blacks, Muslims, and disaffected leftists are joining his army, demonstrating that ideology is not a linear spectrum but a circle, where the so-called “extremes” converge.

Moreover, when Tucker Carlson recently referred to Fuentes as “gay” he wasn’t calling him lame, but was instead referencing the word’s more archaic connotation of “homosexual.” Fuentes did not bother to deny this characterization and has been credibly linked to transgender love interests. It seems Zoomer white supremacy is more aspirational and otherworldly, not based on the material reality of genetic ancestry but on the idealization of America’s past—an ideology in which racial, sexual, and political identities circulate, fold, and entangle into monstrous ideological miscegenations.

Over the years, Fuentes repeatedly challenged Kirk to debate him, but Kirk refused to share the stage with what he considered an anti-Semitic, far-right provocateur. Yet when Kirk extended a hand toward civil discourse with the college campus left—“let’s talk this out”—his Antifa-inspired murderer metaphorically answered with a single, brutal bullet: “No, I prefer to shoot you in the neck.”

What Is To Be Done?

It is always difficult to analyse breaking events like the assassination of Charlie Kirk. Narratives shift as new facts emerge, while waves of partisan slop flood the algorithm, trying to pin blame on the opposing faction. Still, it is hard to ignore the grotesque spectacle of progressives posting celebratory TikToks gloating over Kirk’s death—an uncanny echo of Israeli families picnicking on hillsides overlooking Gaza, cheering as airstrikes obliterate lives and buildings below. The human impulse to revel in an adversary’s destruction is the same; only the scale of devastation differs.

In the United States, every act of political violence inaugurates a tense interlude, where rival camps scramble to shape the story—like spin doctors parsing a debate, verbally joisting over the pools of blood. A decade ago, the right reflexively blamed jihadists; the left rehearsed its catechism that the perennial villain—a straight, conservative white male—must be responsible. Today, the scripts have shifted only slightly: the right now rushes to accuse a “transformer” or “troon” (derisive Zoomer slang for a transsexual), while the left clings to its familiar archetype of the dangerous white conservative male.

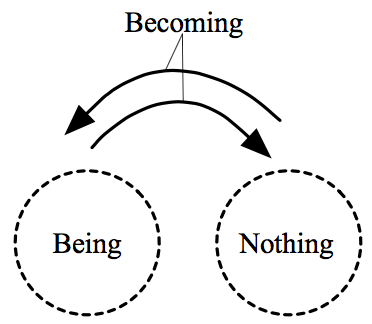

In Kirk’s case, tragic irony reigned. The shooter embodied a uncanny Hegelian sublation: a white male from a conservative background, shacking up with a male-to-female transsexual. Contradiction did not resolve; it was lifted to a higher plane, simultaneously negated and preserved, proving the illusory quality of identity.

In this macabre game of partisan guessing, the right scored the closer hit—but only on points, not by knockout. Both lovers had grown up in conservative households, yet each in his way rejected his straight father figure, escaping the postmodern gulag of white male otherness by embracing minority sexual identities.

As if the contradictions weren’t baroque enough, the shooter reportedly had links to paramilitary Antifa groups—ostensibly anti-fascist, yet exhibiting the discipline and violence they claim to oppose. Opposition mutates into identity; anti-fascism begins to mirror fascism itself. Here again, Hegel’s sublation is evident: negation is lifted, inverted, and turned into a new, impotent form of the original.

Binaries are treacherous. To define oneself solely by negation risks Nietzsche’s axiom: “He who fights with monsters should take care lest he thereby become a monster.”

Today, the progressive left embraces the act but not the actor—they would have preferred a Groyper. Tyler Robinson may yet rise to the status of Luigi Mangione. And if he were to follow the Chelsea Manning path—transforming into a transsexual martyr—he could ascend into a true icon of progressive reaction.

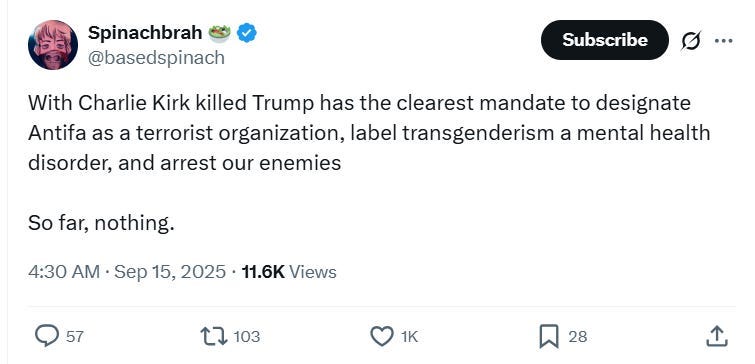

The right faces its own fork: pursue affirmative systemic change, or fall into static reaction. Already, some call for Kirk’s murder to become a Republican “Jan 6th,” a purge of partisan enemies, with Antifa cast in the villainous role once held by the Proud Boys. Yet many doubt that a comfort-seeking boomer like Trump has the will or focus required for such a campaign.

Here, both sides stumble into the same odd trap: the futile game of “getting even.” Balance is a mirage; equivalence cannot exist. The ledger is always odd, the arithmetic partisan. Was Kirk’s death commensurate with George Floyd’s? Each side insists on its own calculation, and the score is always already uneven.

This is no accident. The political establishment cultivates reactive movements, letting them burn themselves out—Antifa in the streets, January 6th in the halls of Congress. If calls for a “9/10” roundup gain traction, they will be tolerated, perhaps even quietly supported, because reaction is safe. What is missing on both left and right is affirmation: the articulation of a New Order that does not merely negate the old, but creates something radically new.

Endless rounds of reaction provide narcotic comfort, a cocoon where nothing changes. Affirmation is perilous: high-risk, high-reward, capable of catastrophe as easily as renewal. Once again, the story of Job again resonates.

Job endures, suffering without revolt. Satan embodies sterile reactivity, tormenting without risk, secure in the impossibility of victory over Yahweh—yet delighting in the power to inflict destruction. Job’s wife, in contrast, represents a darker, potentially Promethean force: the lure of creative destruction. Her cry to “curse God and die” profanes the sacred, clearing a space where something entirely new might emerge. She offers no promise, only negation—a necessary chaos, the gamble that from destruction something novel may take root, even if the outcome is monstrous.

American politics today oscillates among three vectors: Job’s patient endurance, Satan’s sterile ressentiment, and Job’s wife’s destructive affirmation. Each carries its own peril: one traps us in endless suffering, another perpetuates cycles of revenge, and the third dares the terrifying, high-stakes gamble of a New Order. The question hangs: will America endure as Job, react as Satan, or leap with Job’s wife into the unknown—even if what rises from the flames is hideous?

Fuentes is like reductio ad absurdum of racial supremacy. Whatever elite genetic whites are doing is ipso facto the correct politics.