John Boyd: The Subversive Strategist

From mediocre fighter pilot to anti-systemic intellectual, an introduction to USAF Colonel John Boyd, America's supreme strategist.

With so many conformist, ugly-American architypes today prancing across the world stage, never has America been more in need of a subversive intellectual icon. As institutional groupthink cements ideological rigidity, US global power is slowly dissolving. Instead of observing the world, orienting by means of a viable frame of reference, and then directing action, the US is stuck in an endless loop of its own self-deception. Only through acute nonconformity, by shattering establishment self-deception with the hammer of reality, can America get back on a winning path.

US Air Force Colonel John Boyd is an icon illustrating the rebellious intellectual heights Americans must climb. Now recognized as the most innovative strategist of the late-20th century, during his lifetime he was not well known, even within the military. Today as the Ukrainians beg their allies for F-16 fighter jets, few know that the primary institutionally subversive force behind this aviation masterpiece was John Boyd. The F-16 is a monument to what an anti-systemic crusader can achieve.

After Boyd’s death in 1997, his ideas have slowly spread to a wider public, in large part thanks to his six acolytes who accompanied him throughout his intellectual campaigns. Boyd is best known for his OODA-Loop concept (observe, orient, decide, act) that was developed for fighter pilots, but which today transcends its military use and has wide application in business, law enforcement, legal and the evolutionary biology fields. Any conflictual situation on any scale, from unicellular amoeba to gigantic nation-states can be understood through the OODA-Loop concept.

Creative, reformist, intellectual yet grounded in reality, Boyd disdained incompetent leadership. Looking back from today’s vantage point, Boyd was no doubt slightly autistic. Boyd grew up during the Depression in grinding poverty after his father passed away. He claimed, somewhat dubiously, to have only scored 90 on a high school IQ test. But through his unquenchable drive and competitive nature, Boyd canonized fighter pilot tactics, revolutionized aircraft design, and developed an evolutionary theory of strategy. His biographer Robert Coram claims, with slight exaggeration, that “[Boyd] was probably the greatest military theoretician since Sun Tzu.” However, on a personal level, Coram bluntly states that Boyd, “was ill-mannered, he was unkempt, loud, opinionated, intolerant of anyone who disagreed with him, he had the table manners of a five-year old, he was profane, abrasive, he was a terrible father and a worse husband.”

Nevertheless, Boyd built deep lifelong relationships with six acolytes: Michael Wyly, Pierre Sprey, Raymond J. "Ray" Leopold, Franklin "Chuck" Spinney, Jim Burton, and Tom Christie. Several of these men were highly regarded academics or military professionals. Despite their accomplishments, each submitted to Boyd, who served as a Messianic guru to them. He was notorious for phoning at any hour at night to discuss a chapter from the latest book he was reading. After Boyd’s death, his acolytes helped spread his strategic gospel to a wider flock.

Although Boyd held undergraduate degrees in economics and industrial engineering, he was primarily self-taught. His competitiveness drove his intellectual life and Boyd read broadly, not just military history and strategy, but particularly in mathematics, science, physics, political science, evolutionary theory and philosophy.

In the philosophical realm, Boyd had several heavily annotated books on Marx, from whom along with Hegel, Boyd borrowed his dialectical view of the world. There are elements of the Taoist unity of opposites concept in Boyd’s Creation and Destruction theory. Boyd read Nietzsche and eventually developed an outlook very similar to Nietzsche’s Perspectivism concept. Boyd’s OODA-Loop has similarities to Gilles Deleuze’s unorthodox interpretation of Nietzsche’s Eternal Recurrence idea, with a never ending loop of both repetition and difference.

In his book Science, Strategy and War: The strategic theory of John Boyd, author and former F-16 pilot Frans Osinga declares John Boyd was the first postmodern strategist. Osinga argues that Boyd’s strategic concepts reflect the instability and lack of absolute truth that both Einstein’s theory of relativity and Quantum physics wrought on the stable world of Newtonian physics. Osinga shows how Boyd’s eclectic mind combined Gödel’s incompleteness theorem from mathematical logic, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle from physics, and the concept of entropy from thermodynamics to create a synthetic theory of conflict that rejects the concept of absolute truth.

However, Boyd never wrote any books and only finished one paper: Creation and Destruction. Writing was a painful process for Boyd. Thinking, he argued, was evolutionary, ideas were never consummated, while a paper or a book forced an endpoint. Moreover, the military has a tradition of oral communication and so Boyd preferred the medium of briefings. Slides can be added, subtracted or edited as ideas percolate.

Boyd gave masterful briefings. With an immediate audience, there was the constant potential for intellectual combat. Boyd excelled at skilfully shooting down any unfounded critical attacks incoming from his listeners. Since his death, plenty of these briefings have been released to the public. Numerous books have been written on his ideas and many of his acolytes are still actively preaching his thought.

Boyd’s primary mode of social interaction was conflict—his more diplomatic acolytes were forced to socially clean up after his outbursts. For the most part, Boyd’s disdain flowed uphill, targeting his superiors and their powerfully inept organizations. He got away with this behaviour because very senior leaders, always on the lookout for a truthteller, would protect him. A wise leader, knowing his general staff must be incompetent and will only share good news, will find a few honest lower-ranking players to be his eyes and ears towards reality. For example Dick Cheney, among many others, used Boyd this way. Boyd is widely credited for conceiving the “Left Hook” of Operation Desert Storm:

In the meantime, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney consulted one of his favorite military strategists, retired Air Force Colonel John Boyd. During the run up to Desert Storm, Cheney regularly met with Boyd, where Boyd developed “a version of the von Schlieffen plan”. Boyd was intimately familiar with the Battle of Cannae, the Schlieffen plan, as well as the concept of strategic envelopment; he used his vast knowledge of history to inform his strategic advice to the DOD.

Boyd’s warrior desire to win at any cost drove his total war against the military bureaucracy. James G. Burton, in his book The Pentagon Wars: Reformers Challenge the Old Guard, highlights Boyd’s view on bureaucratic yes-men or women:

The practice of purging the ranks of “difficult” subordinates—people who question the wisdom of conventional thinking, who challenge their superiors, who do not automatically salute and say, “yes sir, yes sir, six bags full,” when their superiors speak—over the years has produced a crop of senior officials long on form and short on substance. The long-term result of stifling dissent and discouraging unconventional views, while rewarding those who conform, is an officer corps that is sterile, stagnant, and predictable. Promoting clones, while purging mavericks, is tantamount to incest. We all know the possible long-term effects of generations of incest—feeblemindedness, debilitation, and insanity.

What was true in the 1970’s is doubly true today as years of ideological inbreeding has created the current abomination driving US foreign policy in both parties. As the US jumps from failure to failure, the incestuous ideological inbreeding only intensifies. The two-party system enforces the partisan groupthink Boyd disdained and crushes independent critical thought. These establishment “truths” are maintained through the creation and reinforcing of “mental lenses” that the media and opinion leaders impose on their consumers. Boyd referred to these loops of conventional nonsense as “incestuous amplification.” The most valuable prize that both a strategist or citizen can possess is intellectual independence—the freedom to adopt the orientating lenses that best describe an everchanging reality.

Early in his career, Boyd idealistically believed that his accomplishments would be rewarded with promotion and recognition. But as flocks of enemies rose in the wake of his righteous crusades, he soon realized his Air Force career was going nowhere. This didn’t change him at all. Given the choice between being somebody or doing something, Boyd would choose doing, as he explained to a junior officer:

"one day you will come to a fork in the road," he said. "And you're going to have to make a decision about which direction you want to go." He raised his hand and pointed. "If you go that way you can be somebody. You will have to make compromises and you will have to turn your back on your friends. But you will be a member of the club and you will get promoted and you will get good assignments." Then Boyd raised his other hand and pointed another direction. "Or you can go that way and you can do something — something for your country and for your Air Force and for yourself. If you decide you want to do something, you may not get promoted and you may not get the good assignments and you certainly will not be a favorite of your superiors. But you won't have to compromise yourself. You will be true to your friends and to yourself. And your work might make a difference." He paused and stared into Leopold's eyes and heart. "To be somebody or to do something. In life there is often a roll call. That's when you will have to make a decision. To be or to do? Which way will you go?"

In order to do—to create a valuable “new”—the “old” must be destroyed. Powerful institutions exist to protect their “old” dogmas and ideological rigidity. The agent of destruction may succeed in his ideological quest but the effort will destroy any career path within that organization. To create the ideological space to design his masterpiece, the F-16, Boyd waged a bureaucratic guerrilla campaign against the Air Force’s “Bigger-Faster-Higher-Farther” mindset. In a nutshell, the Air Force was addicted to speed and expense while the frugal Boyd and his acolytes pushed for agile and low-cost fighters, which would allow the purchase of many more planes, to better flood the battlefield.

These institutional wounds heals slowly. To this day, despite his historical achievements, John Boyd is held in low esteem by the US Air Force. Conversely, Boyd is nearly deified by the US Marine Corps, who base much of their current doctrine on his strategic insights.

Analytic deconstruction—Aerial Attack Study

Towards the end of the Korean War, Boyd flew 22 combat missions in an F-86A. An unremarkable wingman, he never fired a shot against an enemy. After the war, Boyd eventually found a teaching position at Fighter Weapons School at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada. The school specialized in air-to-ground combat. Boyd, in his typical arrogant manner, unilaterally rejected this “target-practise” approach. Boyd lived for conflict and so pushed his students to develop air-to-air combat skills. For six years he analysed, deconstructed and broke down into parts the give and take of fighter jet dogfighting tactics.

In most competitive endeavours, the goal is to win the race, the be ahead of the pack. Not so in air combat. In a dogfight, the winning position is found on the opponent’s tail, on their “six” (o’clock). From this position, guns or missiles can destroy the enemy plane. Given the three dimensional domain of air combat, the tactics of dogfighting are extremely complex and counterintuitive. In reviewing US experiences in Korea, Boyd hit upon the concept of “asymmetric fast transient” to flip the tables on an opponent. If an enemy was on your tail, in a move Boyd called “flat plating the bird”, the plane would violently deaccelerate by being practically pulled vertical. Once the pilot recovered control—and assuming the airframe withstood the shock of this “flying manhole” manoeuvre—the pilot should find his enemy in front of him and within his gunsights.

Boyd’s insatiable drive to win was only matched by his bottomless intellectual curiosity. Guided by his asymmetric fast transient concept, he attempted to deconstruct dogfighting and to codify all of its moves and counter-moves. In short, he was creating a playbook for fighter pilots. Previously, air-to-air combat was thought to be too complicated with far too many variables to be organized into a series of chess-like gambits. Instead pilots relied on tacit knowledge—on their intuition and experience. The closest previous attempt at codifying air-to-air combat had been by the German ace Oswald Boelcke after WW1. But his Dicta Boelcke was just a short list of guidelines.

Boyd went much further. Working nights and weekends, fuelled by his relentless internal drive—with no budget or approval from his superiors—Boyd created his first masterpiece. Boyd’s Aerial Attack Study became:

the first comprehensive logical exposition of all known (and some hitherto unknown) fighter tactics in terms of moves and countermoves. Previous tactics manuals were just bags of tricks, without the logic of move and countermove. Boyd did not advocate one maneuver over another but presented the options (and the logic for selecting them) available to a pilot to counter any move his opponent made. The study represented the first time that anyone had based fighter tactics on three-dimensional, rather than two-dimensional, maneuvers.

The moves and countermoves laid out in this study formed the basis for all fighter tactics used by Air Force, Navy, and Marine fighter pilots in Southeast Asia. It is still the basis for tactics used in all jet fighter air forces today. (p. 12)

Boyd pushed his students hard but later received many letters from pilots who flew in Vietnam and thanked Boyd’s ideas and training for getting them back home. Air combat is a contest between the combination of a man and a machine against another. Boyd’s Aerial Attack Study assumed the pilots were flying similar machines. But codifying tactics was only half the job, improving the machines was the next quest for Boyd. But to design the ultimate fighter, Boyd needed a mathematical way to quantify the differences between fighter jets.

Synthetic Creation—Energy-Maneuverability Theory

While studying Industrial Engineering in his early thirties at Georgia Tech, Boyd became obsessed with finding a way to quantify fighter jet performance into a single mathematical formula. While studying the second law of thermodynamics, Boyd had an epiphany. The key to aircraft manoeuvrability—changing direction, speed and/or altitude was the aircraft’s ability to obtain and retain energy.

Once his university studies were finished, Boyd returned to the Air Force and teamed up with Tom Christie, an accomplished mathematician. Together, they slowly developed Energy-Maneuverability Theory (E-M Theory):

The E-M Theory, at its simplest, is a method to determine the specific energy rate of an aircraft. This is what every fighter pilot wants to know. If I am at 30,000 feet and 450 knots and pull six Gs, how fast am I gaining or losing energy? Can my adversary gain or lose energy faster than I can? In an equation, specific energy rate is denoted by “Ps” (pronounced “p sub s”). The state of any aircraft in any flight regime can be defined with Boyd’s simple equation: V, or thrust minus drag over weight, multiplied by velocity. This is the core of E-M.

Elegance is one of the most important attributes of an equation. The briefer and simpler an equation is, the more elegant it is. E = mc 2 is, of course, the ultimate example. Boyd’s theory is not only elegant, but it is simple, beautiful, and revolutionary. And it is so obvious. When people looked at it, they invariably had one of two reactions: they either slammed a hand to their forehead and said, “Why didn’t I think of that?” or said it had been done before—nothing so simple could have remained undiscovered for so long.

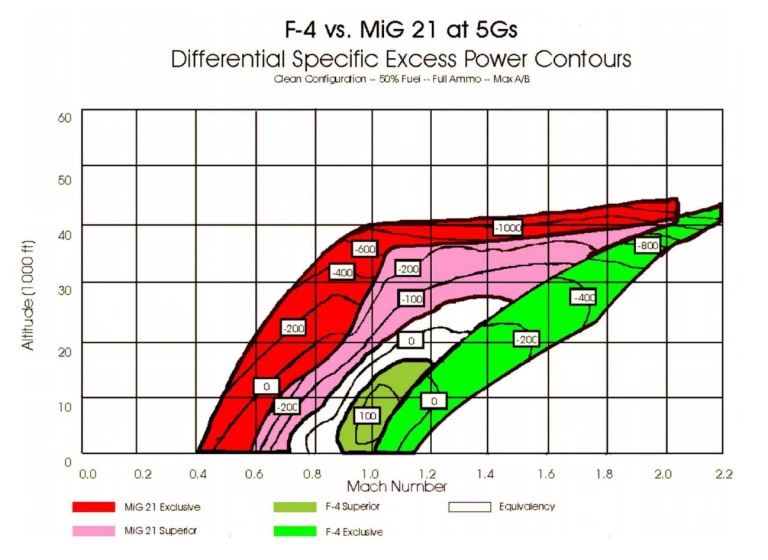

For Boyd’s theory to be useful, the relative differences between aircraft needed to be calculated to compare performance. Boyd naturally sought data from Soviet fighter jets. After many bureaucratic struggles he obtained this information. But once he and Christie plugged the data into their primitive computers, the results astounded him:

As Boyd probed deeper into the comparisons between American and Soviet aircraft, he began to notice a disturbing trend in the chart overlays. Blue was good and red was bad and there was entirely too much red in many of the charts. This meant that in a big part of the performance envelope, Soviet aircraft were superior to U.S. aircraft. This could not be true. U.S. fighter aircraft were the best in the world. If Boyd briefed this—if he showed, for instance, that the F-4 Phantom was too heavy and did not have enough wing to win a turning fight with a MiG-21 at high altitude—and he was wrong, it would be the end of E-M. If he said, as the E-M charts showed, that the only place for an F-4 to successfully fight the MiG-21 was at low altitude and high speed, he had better be right. And the F-111 chart was one that would cause serious heartburn to any general who saw it—the chart was solid red: Soviet aircraft could defeat the F-111 at any altitude, at any airspeed, in any part of the flight envelope.

Boyd, along with most Americans, oriented himself in the world through a lens of American superiority. But this world-view was now fractured by his own theory. He spent months challenging his conclusions, testing his results, questioning the intelligence data on the Soviet aircraft, but in the end not much changed: the Soviet fighters were in several important areas superior to US planes.

As his briefing worked its way up the food chain of senior officers, Boyd had to traverse of hail of flack and accusations of disloyalty. Many hot-headed challengers appeared at his briefings but since Boyd knew the material better than anyone, and had already stress-tested it himself against any weaknesses, he calmly obliterated the critics one after another.

At the same time empirical reality from Vietnam flowed in and gave material, real-world credence to Boyd’s mathematical ideas:

Two other F-105s were shot down by cannon fire.

When four MiGs attack four F-105s and the score is 2–0 in favor of the MiGs, people at the highest levels in the Pentagon want to know what the hell is going on. How can the U.S. Air Force so decisively lose an air-to-air engagement with MiGs? Was the problem with the pilots, the aircraft, or the tactics?

Several months later four F-105s were lost in a single strike against a surface-to-air missile (SAM) site.

Boyd and Christie were summoned to the Pentagon.

The final institutional resistance to Boyd’s E-M Theory fell during 1967:

If there was a turning point, a time when even the most jingoistic Air Force general at last understood that Communist forces could build fighter aircraft superior to anything that America put in the air, it was Vietnam in 1967, the worst year of the war for the Air Force. It finally sank in that, as Boyd had said for years, the Air Force had no true air-to-air fighter. It is said that combat is the ultimate and unkindest judge of fighter aircraft. That was certainly true in Vietnam. The long-boasted-about ten-to-one exchange ratio from Korea sank close to parity in North Vietnam; at one time it even favored the North Vietnamese.

Robert Coram, in his biography, Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the World puts E-M Theory in its historic context:

After E-M, nothing was ever the same in aviation. E-M was as clear a line of demarcation between the old and the new as was the shift from the Copernican world to the Newtonian world. Knowledge gained from E-M made the F-15 and F-16 the finest aircraft of their type in the world. Boyd is acknowledged as the father of those two aircraft.

A more accurate reading was that the F-15 was Boyd’s “red-headed stepchild” as much of his design input had been rejected. Boyd immediately went to work to undermine it even before production began. He and a group of fellow travellers—called the “Fighter Mafia”—went to work designing his “golden child” the F-16 in the shadows. By playing the Navy and Air Force against each other, they managed to get the F-16 into production. Paraphrasing Boyd, the Air Force was more motivated to fight the Navy than they were in confronting the Russians.

Sublation: Boyd’s masterpiece, the F-16

Boyd’s obituary in the New York Times gives a good summary of his contribution to the F-16:

Although he had allies in the Pentagon, Congress and business, Colonel Boyd's ideas often went against the grain of a military-industrial bureaucracy devoted to the procurement of the most advanced, most expensive and (not coincidentally, he felt) most profitable planes.

Although his design ideas helped give the F-15 a big, high-visibility canopy, his major triumph was the F-16, a plane lacking many of the F-15's high-tech, expensive features, but which is far more agile and costs less than half as much, allowing for the purchase of many more of them for a given expenditure.

Top Air Force officers were so opposed to the concept of producing a plane that did not expand on the F-15's cutting edge technology that Colonel Boyd and some civilian allies developed it in secret.

The plane was hailed for its performance in the Persian Gulf war, a war whose very strategy of quick, flexible response was based largely on ideas Colonel Boyd had been promoting for years.

In recent weeks, the supposedly renowned Patriot air defense system has fallen on hard times in Ukraine at the hands of hypersonic Russia missiles. Not only are Russia’s missiles superior, but their S-400 air defense system is heads and shoulders above the Patriot system. In reading about Boyd’s institutional escapades back in the 60’s and 70’s, one is struck by how flexible the military hierarchy actually was in letting such a brilliant but maverick problem child rampage through their institutions. How would a John Boyd-type rebel fare in today’s Pentagon if he told the truth about the Patriot system? Are there even any rebels allowed in the Pentagon, who refuse to drink the institutional Kool-Aid, fighting to develop lower cost yet more effective weapons?

One fundamental tenet of Boyd’s thought is that there is no single truth. This idea is considered postmodern and often controversial. But the current onslaught of information warfare and heavy government propaganda—which claims the status of absolute truth— proves the need to maintain flexibility in the lenses we use to orient ourselves in the world. Today it takes the mental agility of an F-16 to dogfight with the system’s “truths.” Boyd sought reality and saw “truth” as its enemy. Flexibility and creativity allows both strategists and citizens a closer approximation to reality and helps evade the system’s loops of incestuous amplification.

I very much enjoyed reading and even re-reading your piece, despite the fact that I am neither an American nor a military man. In my opinion your piece raises many issues with regards to the nature of bureaucracy as a useful system of governance in the face of the seemingly every rapid change of reality. A maverick like Boyd was allowed to rampage through the institutions back in the 60's and 70's, but would that be the case today? I think the question is answered by simply asking the question. However, what was different back in the 60's and 70's? It reminds me of what I read recently about there having been a big reshuffle of the Russian brass as a response to the changing reality on the battlefield in Ukraine (politicians out and competent military strategists up). In my opinion competition defined as a comparison of different levels of organisation between peers may be of importance here. Competition forces adaptation to the ever changing reality which in turn requires changes of organisation on both sides. However, what if your ideology tells you that you are omnipotent and that your level of organisation is the best? Would an organisation that views itself as omnipotent see a need for and thus allow any rebels within its ranks?