Grounding Constellations

Second in a series of sketches exploring Zionism: Tracing lines from the Pale of Settlement in Ukraine to Palestine, where the celestial metaphor of nationalism meets the grounded reality of conflict.

We gaze toward a sky dense with stars, but never leave them as they are. Through acts of selection, we trace certain shapes—a dipper, a plough, a lion—enjoining a chosen few while fainter points are relegated, the countless remainder dismissed as mere background. Every constellation is a product of exclusion, setting form against multiplicity.

Such pattern-making, universal to human instinct, answers the need for order: to enclose and shelter ourselves amid cosmic excess. Constellations impose meaning on chaos, anchoring myth and navigation, yet each culture's unique configuration overlays, without erasing, others. Planets—unsettled wanderers—drift through these patterns, quietly reshaping them.

But to draw a constellation is, inevitably, to draw a border. Order emerges in defining figure and ground, establishing the liminal spaces between belonging and displacement. Historiography operates likewise: history is a crowded firmament, its events scattered until chosen moments are bound together, some shining as golden ages, others casting shadows to be avoided. Our navigation—by hope or despair—depends on such selective illumination.

Patterns, however, are fluid. Revisionists—heretics of inherited memory—redraw the historical sky: golden ages recast as times of conquest, dark eras unveiled as fertile silences. This perpetual re-charting sustains historical inquiry—a dialectic between mapped certainties and the uncharted dark.

Empires mirror this labour on the ground, assembling disparate peoples as constellations in an imposed design. Promising order, they construct hierarchies: some lights dominate, others fade. Such arrangements offer orientation, but only by casting entire peoples into shadow.

If a subordinate star claims its own radiance, the drive for independence is set in motion—a singularity sought, even as the coherence of nationhood demands its own internal exclusions. Nationalism fuses divergent lights into apparent unity, mirroring the same process of exclusion by which empires and constellations first took shape. In breaking free, the newly sovereign may eclipse its own “others within,” perpetuating the cycle from marginalization to marginalizer.

Ideology sets the scale, refracting the eternal pattern of inclusion and exclusion through new lenses of sovereignty and belonging.

Today, Europe’s political project attempts radical universalism, dissolving prior national configurations into abstract dissolution—a fate marked by conformist anonymity for stars once vibrant and distinct.

Elsewhere, as in Palestine, Zionism drew a new constellation not alongside but over the old, overwriting and occluding previous lights.

Zionism forged ideological unity from diaspora, anchored in the geography and myth of Zion—aggregating scattered communities into a singular objective, a lodestar amid the shifting constellations of exile. For many, it functioned as a North Star: a point of orientation that promised direction and coherence within historical night. Yet this unity required the eclipse of former ties, replicating the exclusionary logic from which it sought to escape; thus, national self-creation arrived shadowed by new categories of otherness.

The Zionist ideological constellation was composite, assembled from strands of Political, Labour, Revisionist, Cultural, and Religious Zionism—each exerting its own force and sometimes collision. Yet the surrounding darkness remained: Palestinian communities became counterpoints, their own histories and claims colliding with the emergent order, a dialogue of light and shadow.

Constellations are enlivened by planetary wanderers—charismatic leaders whose motion reshapes ideological landscapes. Herzl, Ha’am, Jabotinsky, Ben-Gurion, Kook—all moved among these currents, binding or fracturing them, giving luminous form to projects that, as ever, transformed exclusion into guiding light.

It is the enduring human act: to forge illumination by tracing constellations—selecting stars that align to an ideology—while countless others remain unchosen, scattered in the shadows beyond the constellation’s tragic light.

Prelude to Zionism: Imperial Strife in Ukraine

The seed of the modern Israeli-Palestinian conflict was sown not in the sacred soil of Jerusalem but in the shifting borderlands where two waning imperial stars—the Ottoman and Russian empires—clashed. Cities like Odessa and other ports along the Black Sea coastline marked the volatile frontier where Russian and Ottoman ambitions collided, their destinies intertwined with the fate of millions—Jews foremost among them, and the Ukrainian peasantry increasingly stirred amid the tides of upheaval. The conflict’s contested borders, inscribed by imperial collapse rather than ancient prophecy, were forged in the crucible of nineteenth-century geopolitics decades before the First World War would unravel the old order.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the "Eastern Question" obsessed European chancelleries. How could the inevitable decline of the “Sick Man of Europe,” the Ottoman Empire, be managed? Russia’s answer was relentless expansionism: southward, toward the warm-water ports of the Black Sea.

Obstructing this advance was the Crimean Khanate, a vassal of Ottoman suzerainty whose economy thrived on slave raids funnelling tens of thousands into Ottoman markets from the steppes of modern Ukraine and southern Russia. By the late eighteenth century, Russia decisively crushed this frontier power, annexing Crimea in 1783 and solemnly declaring victory over Ottoman suzerainty. The khanate’s former borders now overlay Ukraine’s current conflict zones—an eerie echo of the Russian desire for security (against then slave-raiders, now NATO) resulting in creeping imperial expansion.

Concurrently, Russia pressed westward into the fertile Balkans. The Crimean War (1853–1856) was a violent prelude to future confrontations—a desperate British and French coalition willing to curb Russia’s Mediterranean ambitions and preserve the European balance of power. Their dread was that Ottoman collapse would birth a Russian colossus astride vital sea lanes.

That very Black Sea coastline remains today the arena for a tense reprise: Russia versus NATO-backed Ukrainian resistance. This strategic pivot of Eurasia, identified by Zbigniew Brzezinski as the indispensable “grand chessboard,” persists as a perennial geostrategic prize.

From Pale to Palestine

In its imperial expansion, the Russian Empire absorbed millions foreign to the Tsar’s ideal of Orthodox Russian homogeneity. Faced with this challenge—most acutely its vast new Jewish population after partitioning Poland—Russia did not seek assimilation but quarantine.

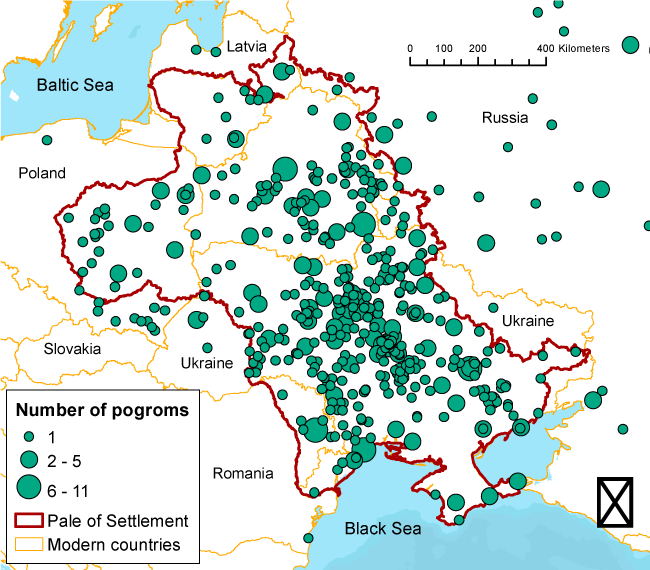

The solution was the Pale of Settlement. Established in the late eighteenth century and encompassing much of today's Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, and Poland, the Pale was a vast borderland ghetto—a constellation of confinement. Jews were legally forbidden from residing permanently outside its borders, barred not only from settling in the Russian interior but often from mere travel there. They were seen as a designated alien nation, trapped where imperial tensions were highest.

Prior to 1881, Jewish life within the Pale—though brutal and humiliating—operated under a fragile but established order. Certain Jews could obtain limited permits to travel or reside beyond the Pale, and an exploitative modus vivendi maintained a tense, if unstable, calm.

The assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 by revolutionaries, with minimal direct Jewish involvement, became the pretext for radical change. The state responded not with targeted justice, but with sweeping collective punishment: the May Laws of 1882. These enacted economic strangulation and accelerated expulsions, transforming the Pale from a zone of containment into an instrument of systemic pressure and exclusion. Polemic Jewish activists of that era may have referred to these settlements as “open-air prisons”—a rash of Gaza-style points of repression, dotting the vast Ukrainian steppe.

The human cost of this shift is reflected in the experience of Chaim Weizmann, a chemist, leading Zionist diplomat, and eventual first president of Israel. Often described as one of the founding fathers of political Zionism and a key figure in securing British support for the movement, Weizmann recalled, as a young man living in the Pale before exile, the absurd humiliation of clandestinely entering Moscow for a meeting only to have it cancelled. Unable to be legally present or seen openly, he was forced to pay a cab driver to circle the city until he could slip back to the Pale by train. His offense was not action but identity—the condition of being an “other within,” a Jew whose very presence beyond the designated zone was deemed unlawful and dangerous.

Pogroms: From Ukraine to Palestine

This shift in imperial policy was accompanied and intensified by a wave of violent outbreaks known as pogroms—organized, often suspected to be state-tolerated attacks against Jewish communities that swept through the Pale and adjoining regions during the 1880s and beyond. Pogroms exceeded mere anti-Semitic fury; they were social catastrophes rooted in the volatile interplay of economic crisis, nationalist agitation, and the Tsarist state’s fragile authority. In these brutal riots, Jewish homes and businesses were looted, communities terrorized, and lives extinguished. The pogroms functioned as instruments of collective punishment and intimidation, signalling the fragility of Jewish existence under imperial rule and the limits of the earlier “stable” containment. For many Jews, pogroms crystallized the necessity of decisive escape or transformation—fuelling emigration, radical political movements, and ultimately, the Zionist project as refuge and national promise.

Yet, to understand pogroms solely as anti-Semitic violence risks oversimplification. Many perpetrators were Ukrainian peasants caught in the turbulence of imperial decline and economic precarity. These peasants were shedding their Ruthenian identities amid the ethnonational ferment engendered by Polish and Russian imperial domination. Inspired and symbolized by cultural figures like Taras Shevchenko, Ukrainian nationalism emerged as a powerful, though complex, resistance to imperial rule.

Jews, frequently perceived as intermediaries of imperial authority or components of exploitative economic structures, became inextricably linked and vulnerable participants in this wider upheaval. This shared context of imperial “churn” forged parallel trajectories: while Jews adopted Zionism as both refuge and political project in response to exclusion and violence, many Ukrainians embraced nationalism as liberation from centuries of imperial domination.

This complex legacy of coexistence, resentment, and shared oppression is rarely granted full nuance in contemporary narratives. In particular, the Western embrace and promotion of Ukrainian nationalism—fuelled by Cold War desires to fragment the USSR—has often resulted in a sanitized memory of figures like Shevchenko, whose works and legacies are sometimes detached from their more ambivalent or contested historical contexts. While Shevchenko remains an enduring national bard, a closer examination reveals his—and Ukrainian nationalism’s—complicated relationships not only with imperial powers but also with Jewish communities.

Of course, pogroms were not acts solely of Ukrainian peasants; blame cannot be localized without recognizing broader imperial provocations, political manipulations, and social fractures. Nonetheless, this intersection underscores how nationalist movements—even those resisting empire—could and did reproduce exclusionary logics—mirroring and at times participating in the cycle of defining and expelling the “other.”

Casting a Palestinian Pale

This pattern—where a catalytic atrocity triggers a state’s adoption of total siege and collective retribution—is neither unique nor confined to one era. It finds a stark modern echo in the Israeli administration of Palestinian territories following the 1967 occupation of Gaza and the West Bank.

For decades, Israeli rule operated a system of conditional, exploitative integration. The permit system controlling Palestinian labour, while humiliating and discriminatory, created a regulated flow of people and capital—a mechanism generating dependence and limited mobility. The attacks of October 7, 2023 shattered this precarious framework. Israel’s response extended far beyond military retaliation, imposing a total siege on Gaza, severing supplies of food, water, and energy, and freezing movement and work permits in the West Bank: a conscious policy of collective punishment.

The parallel between Tsarist Russia and contemporary Israel lies not in moral equivalence but in a shared strategic logic: designating an entire population as a collective threat and revoking conditional rights wholesale. Both the May Laws and the post-October 7 siege sought to break collective will by making life unliveable, betting on desperation to provoke ethnic displacement.

Yet the outcomes diverged starkly. For Jews under Tsarist Russia, this pressure opened an exodus—a tragic valve of flight. For Palestinians in Gaza, it forged sumud, a grim steadfastness and resistance born of siege.

From this crucible of imposed crisis arose Zionist settlement—not as an isolated act of return, but as a consequence of imperial rupture. The national destinies of Jews fleeing confinement and Palestinians resisting dispossession were thus shaped in recursive opposition: one exodus fuelling another; one claim to land forged in flight from another’s oppression.

Grounded constellations were redrawn. New national iconography—the lion, the olive tree, the bison—were traced across contested terrain, connecting points of light while dimming others. On the ground, these celestial patterns materialized in the violent birth of states and the grim cartography of partition: the contested borders of Israel and Palestine, and the blood-soaked frontiers of Ukraine.

What emerges is a materialist truth: nations, like constellations, are not primordial magic but political constructs, made and unmade through the unrelenting mechanics of history—the drawing of borders, the exclusion of others, and the struggle to orient oneself beneath a transformed and transforming sky.

Read the first essay here: Moving Home: Roots, Routes and Ruins

Next in the series: Primitive Zionism: Why the First Aliyah Failed.

Kevin - great article. Sorry for the delay but just got around to reading it. I currently have a great YouTube channel playing in the background called "Jerusalem Walker". Similar to the other ubiquitous "walking" channels, he has multiple channels where he just walks around Jerusalem and other cities in Israel and films normal life. I must admit that modern Israel is a pretty remarkable country and that Modern, Orthodox Jews (i.e. not Hasidim) have really found a successful balance between modernity and "archaism".

Anyways, not to get off topic but what are your thoughts on the future of Christianity in the West, including Russia? Do you see a Zionist type rebirth? I'm actually quite pessimistic. In Russia, for example, WW2 has taken on a spiritual meaning there and seems to resonate more with the people (look up Immortal Regiment marches in St. Petersburg or visits to the huge monument in Volgograd). It really huge taken on a religious level of significance. From a distance, I actually don't see that level of passion in Christianity at a truly spiritual level. Perhaps we are in the early process of forming a new religion in what was formerly Christendom? Happy to hear your thoughts.

Hi kevin great article. Sorry if my request doesn't relate to this article but i recently fthink i found and article of yours talking about the "technofeudalism" or "neofeudalism" and why was it wrong to use that term to describe the actual sistem. the roblem is i dont know where to find it, could you direct me there please? i would appreciate it, thanks