Forging Capitalism

A parallax view through the lenses of Fernand Braudel and Karl Marx; how China's post-Maoist small business renaissance propelled its current economic mastery.

Lone and unveiled, the word “capitalism” casts a tinge of woe. Qualifiers such as state, crony, free-market or monopoly shroud its cryptic aura. Activists fighting it will deploy the taboo power of its uncloaked form, all the while being enticed by its globalizing tendencies. Common-sense critics may hold a superficial fetish for it, but are repelled by the radical change it wroughts. After all, under capitalism, “all that is solid melts into air, all that is sacred is profaned.”

Karl Marx’s charge was scrutinizing the naked reality of capital. As if he were conducting a sort of economic metallurgy, Marx attempted to discern its molecular bonding, grain formations, and alloy possibilities. Did this familiarity with its inner workings impel Marx towards anti-capitalism? No. Far from despising it as he occasionally feigned, a closer reading demonstrates that Marx desired to usurp control over the sumptuous capitalist machine. Allied with the business class, Marx’s primary enemy was feudal reactionaries—landlords who wanted to go back to a more ordered and sacred time:

Rent of land is conservative, profit is progressive; rent of land is national, profit is cosmopolitan; rent of land believes in the State Church, profit is a dissenter by birth.

While he certainly noted flaws, such as a tendency towards declining rates of profit, Marx anticipated capitalism’s bright potential for the progressive assemblage of social cooperation. Its factories, machines, and armies of workers accelerated human productive capabilities and heaped material wealth upon mankind—albeit in a tragically clumpy manner. Once fully developed, this glorious business machine would offer humankind a happy ending of abundance and freedom. But this general prosperity would only occur if this machine were mastered by the right hands.

Marx came of age in the 1840’s during a period of fervent and upheaval careening towards the failed European revolutions of 1848. The core disturbance driving this agitation was the rise of capitalism:

The factory system rose alongside the artisan guild system, slowly destroying the latter as it did so. Artisans at all levels—masters, journeymen, and apprentices—feared and suffered the resulting damage. Yet while commonly injured by the rising factory system, lines of cleavage appeared soon enough between journeymen and those masters who could hire larger numbers of unemployed workers; some of the masters began to set up what were in effect small factories. By the time of the depression of the late 1840s, journeymen were increasingly desperate and alienated, and they became increasingly involved in many political projects and secret societies.

Journeymen, as the name hints, travelled to neighbouring countries, gathering skills by absorbing alternative techniques and mastering the latest innovations of their trades. As artisan agitation rose, radical groups coalesced and connected. Striving to preserve their way of life, the journeymen waged combat against the encroaching factory system.

Marx vehemently assailed this stance. His doctrine of Communism held the new order’s flower could only blossom from the brimming bud of a previous capitalist epoch. According to Marx, not violent action, but instead radical passivity (covered by fiery yet empty rhetoric) was the order of the day.

Events came to a head after Marx and his wealthy entourage were invited to join the League of the Just, a revolutionary cell headed by the radical autodidact tailor Wilhelm Weitling. At a meeting in Brussels, in a battle between an intellectual rhetorician and a self-taught working man, Marx executed a hostile takeover of the group. In his book Against Fragmentation: The Origins of Marxism and the Sociology of Intellectuals, Alvin Geitner describes the aftermath:

According to Weitling’s letter, Marx had argued that, “ as for the realization of communism, there can be no talk of it to begin with; the bourgeoisie must first come to the helm.” Thus a difference between them was whether it was (in Mao’s words) “always right to rebel” or whether, as Marx argued against the Utopians (and according to Weitling, that night, too) that a revolution without an industrial foundation created by the bourgeoisie would be premature and doomed to fail. Weitling’s distressed letter to Hess expressed the fear that Marx meant to destroy him in the press which, Weitling stressed, was available to Marx because of sponsorship by the rich: “ Rich people have made him an editor, voila tout” (p. 99)

With Weitling out of the way, the task of authoring the Communist Manifesto (CM) fell to Marx, an ideologue with a PhD in philosophy, and Engels, the son of an industrialist. Despite the CM’s reputation for radical agitation, its primary goal was to temper any immediate worker action—giving time for the splendid capitalist system to grow.

On the CM’s 100th anniversary in 1948, economist Joseph Schumpeter noted the gushing approval Marx poured on the “bourgeoisie” (best translated as business leaders):

The first thing about the "economics proper" of the Communist Manifesto that must strike every reader—and a socialist reader still more than a nonsocialist one—is this: After having blocked out the historical background of capitalist development in a few strong strokes that are substantially correct, Marx launched out on a panegyric [glowing tribute] upon bourgeois achievement that has no equal in economic literature. The bourgeoisie "has been the first to show what man's activity can bring about. It has accomplished wonders far surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic cathedrals" and "by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production . . . draws all nations, even the most barbarian, into civilization . . . it has created enormous cities" and ' during its rule of scarce one hundred years has erected more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together . . ." and so forth. No reputable "bourgeois" economist of that or any other time—certainly not Adam Smith or J. S. Mill—ever said as much as this. Observe, in particular, the emphasis upon the creative role of the business class […].

According to Marx, in all its horror, capitalism must be allowed to foster man’s innate abilities to organize and produce wealth in unimaginable grandeur. The “right hands” should only then intervene as the machine reaches its limits and starts to self-destruct. Although there was plenty of chatter about “a dictatorship of the proletariat,” Marx was clear from the beginning the new masters would be Communist intellectuals:

Finally, in times when the class struggle nears the decisive hour, the progress of dissolution going on within the ruling class, in fact within the whole range of old society, assumes such a violent, glaring character, that a small section of the ruling class cuts itself adrift, and joins the revolutionary class, the class that holds the future in its hands. Just as, therefore, at an earlier period, a section of the nobility went over to the bourgeoisie, so now a portion of the bourgeoisie goes over to the proletariat, and in particular, a portion of the bourgeois ideologists, who have raised themselves to the level of comprehending theoretically the historical movement as a whole.

The idea of a pointy-headed Marxist in control of the global capitalist machine may seem fanciful. Marx spent the rest of his life in exile, frequenting the reading rooms of the British Museum, pouring over economic data and theorizing the inner-workings of capital. Despite all this preparation, he died an apparent failure.

It’s tempting to feel sorry for artisans like Weitling. Fuelled by a creative feudal spirit, most of their soul-pleasing craftwork practices were crushed by the alienation of mass machine-made commodities. However, more than a century and a half later, the first step of Marx’s “bourgeois ideologist” prophesy came true. During his reign as Chinese leader, President Xi—who holds a PhD in Marxist Ideology—became master of the global capitalist machine.

During the second half of the 20th century, as America prospered, lawyers gained dominance within its ruling elite. While effective for prosecuting regime apostates, law degrees are not conducive to building things. Under the yoke of the attorneys, much of America’s power-producing capitalist machine was dismantled and exiled to China. Some innovative remnants did emerge on the West Coast, but the Rust Belt and crumbling infrastructure are the legacy of what too many lawyers bring to the economic realm.

In Rise of the Red Engineers: The Cultural Revolution and the Origins of China's New Class, Joel Andreas describes the rise of a technically adept ruling class during the same time period. An engineer’s pure instinct is to connect and build wealth-producing assemblages. If the elite you have are civil engineers, the solution to every problem tends to be a new infrastructure project.

But with the preliminary goal of capture accomplished, the main mission Marx assigned to this Philosopher-Engineer Xi remains forging capitalism into a sword capable of producing a Communist society. Only through the careful manipulation of capital’s essential characteristics is such a feat possible. The Soviet attempt ended in abject failure, a trajectory Maoist China closely tracked. Not only had Soviet and Red Chinese leaders ignored Marx’s pleas to Wilhelm Weitling to wait until the prosperity machine had developed before taking power. Worse, once in charge of Russia and China, these 20th century communists misunderstood basic concepts concerning the molecular qualities of capital.

Forging capital into a world dominating sword

While the casting process—the pouring of bright yellow-orange molten iron into a mold—is cinematically appealing, an iron sword is much stronger when forged. The process of heating the iron to a point of malleability and then pounding it into shape respects the metal’s internal will and deeper molecular organization:

In other words, the blacksmith treated metals as active materials, pregnant with morphogenetic capabilities, and his role was that of teasing a form out of them, of guiding, through a series of processes (heating, annealing, quenching, hammering), the emergence of a form, a form in which the materials themselves had a say.

Forging is better because “by mechanically deforming the heated metal under tightly controlled conditions, forging produces predictable and uniform grain size and flow characteristics.” In contrast, the act of melting iron down and streaming it into any random shape is an act of distorting the material past its ideal configuration. Cast iron is much weaker than forged.

The craft of metallurgy developed over millennia of experimentation. Reaching successive plateaus of achievement brought the metalsmith closer to understanding the inner will of each metal.

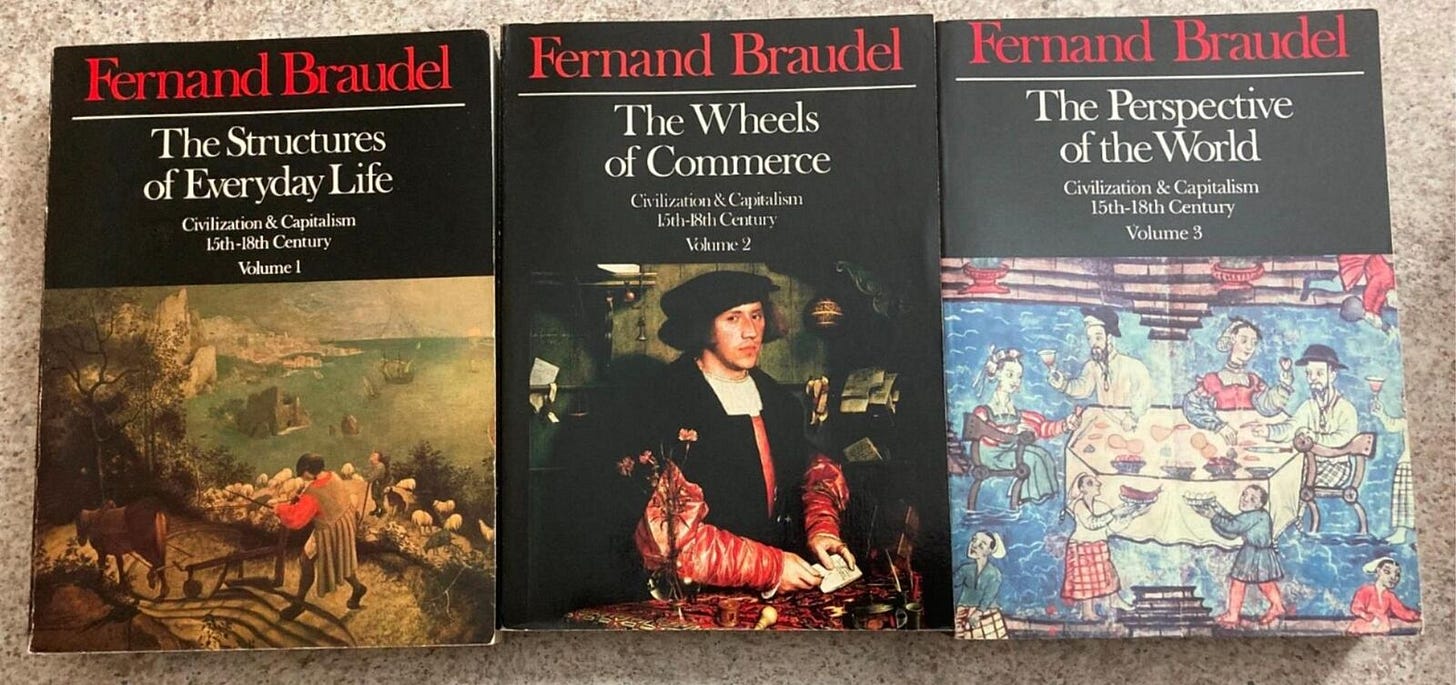

Developing a system of capitalism that is robust yet not brittle follows a similar path of trial and error. One of the finest practitioners of the rare art of “capitallurgy” was French historian Fernand Braudel.

Braudel’s Triad: Pre-market - Market - Anti-market

Fernand Braudel’s interdisciplinary “total history” approach eschewed limits and combined geology, sociology and economics into a vast historical realm. Braudellian “geohistory” started with the topographical facts of the land and then set the daily life of its inhabitants centre stage. Deeply rooted in material reality, Braudel was not a theorist. Nonetheless, his three-level descriptive model of economic life remains a powerful framework from which to conceptualize social issues. Through his method of concrete observation, he nimbly describes the nature of capitalism in a most counterintuitive manner.

Braudel’s three-level structure of economic life spans the history of mankind. In the basement is what Braudel calls “material life.” This is a subsistence economy where self-sufficient communal societies engage in only symbolic trade with neighbours. For most of human existence this was the only economic level and it still exists in many parts of the world. Dark and shadowy to the historian, subsistence economies flourished in pre-literate society, which lack records. Inward looking, Braudel describes its ‘inflexibility, inertia, and slow-motion characteristic…” Money is unnecessary as commodities were not traded per se. Material life is an unkept footpath.

As a subsistence economy prospers, surpluses accumulate. As the society turns outward a new economic level surfaces—the market economy. To Braudel, this was not capitalism. Budding commodity surpluses are at first consumed through internal culture (feasts, festivals), or external symbolic exchange with (gifts, potlatch). But eventually this surplus production is exchanged with neighbouring tribes for other commodities. This trade slowly evolves and becomes formalized into markets, with primitive forms of money simplifying exchange. Once mature, a market economy is stable and transparent--profits are predictable and steady. Based on gentle capillary flows of money and goods, a market economy is outward looking, and exceptionally large geographic areas slowly and organically become connected through ebbing small scale trade. For example, in the 18th century, the entire Eurasian continent was interconnected into one market. Market economies are picturesque country lanes.

While markets have thrived all over the globe for thousands of years capitalism emerged in 15th century Northern Italy. Although on the top level of Braudel’s system, the inner workings of capitalism are for the most part hidden from the historians because that’s the way capitalists will have it. In what may come as a surprise to some, Braudel defines capitalism as the anti-market. The goal of capitalism is not fierce competition. Rather, huge profits through speculation and the exploitation of monopoly positions are sought. “The capitalist game only concerned the unusual, the very special, or the very long distance connection. . . . It was a world of speculation.” Impressive flows of goods and wealth are now through arteries and jugular veins. According to Braudel, "where profit reaches very high voltages, there and there alone is capitalism.” Capitalism is the zone where "certain groups of privileged actors were engaged in circuits and calculations that ordinary people knew nothing of." Capitalists practiced "a sophisticated art open only to a few initiates at most.” And that “the capitalist game only concerned the unusual, the very special, or the very long-distance connection.” Capitalism is a motorway ploughing through the countryside.

Capitalism feeds on the two lower levels but never exists on its own. It’s the market level that provides artisanal shelter. Typically cities are dense nodes of capitalism, rural trad-life hosts softer market economy spaces. Perhaps this explains urban anti-capitalism despite activists imbibing its universalist vibes. And do rural folk wax poetically about capitalism because they misrecognize it in their Braudellian market economy serenity?

Marx himself recognized the difference between the market and capitalist levels, even if he didn’t use Braudel’s terminology. In Chapter 33 of Capital, he sarcastically asks how to cure pre-Civil War America from the “anti-capitalistic cancer of the colonies.”

Free Americans, who cultivate the soil, follow many other occupations. Some portion of the furniture and tools which they use is commonly made by themselves. They frequently build their own houses, and carry to market, at whatever distance, the produce of their own industry. They are spinners and weavers; they make soap and candles, as well as, in many cases, shoes and clothes for their own use. In America the cultivation of land is often the secondary pursuit of a blacksmith, a miller or a shopkeeper.

Braudel’s concrete observations, much like a metalsmith’s secrets, are technical and not theoretical. Working in harmony with the nature of capital makes the difference between casting a brittle society or forging a great power capable of propelling the world towards Marx’s millennialist visions.

Casting Capital—Stalin’s no capitalists big or small policy

Once wrested from the Czar’s death grip by the Soviets, Russia’s retrograde economic plight spurred a rushed transformation akin to casting capital. Stalin’s assertion was that the Soviet Union would be rid of “capitalists small or big.” This was a tragic mistake and contrary to Marx’s doctrine of building communism on the back of capitalism.

Through barbaric policies, particularly in the countryside, Bolshevik impatience annihilated the two lower levels of Braudel’s system while desperately trying to fill an almost empty state capitalist level. While individuals were allowed to perform petty trade (shoemaker, tailor), the category of capitalism was entered upon hiring employees. The Soviets banned most market exchange and terrorized small business under the banner of eradicating the “reactionary petty bourgeois”. Despite suppressing both small business and peasant “kulaks”, the USSR made great progress on the industrial level. Just enough production capacity was in place during WW2 to emerge victoriously. Soviet factories produced at least 100,000 tanks. But as time went on the brittleness and internal weaknesses of their system of cast capitalism caused deterioration.

In the industrial realm, the Soviets were enamoured with Fordism, and its mammoth factories and its precise worker choreography. They attempted the same strategy on the agricultural sector. Through the process of collectivization, Stalin sought to accumulate capital through grain surpluses that would flow towards industry from his enormous farm factories. There were historical precedents. Agricultural surpluses did contribute to Western Europe’s forging of capitalism. But in England, the process took centuries while the Soviets worked in 5-year plans.

The Soviets met stubborn defiance from rural peasants, especially in the Ukraine. These petty farmers had thrived for centuries in their small market culture and were not interested in joining gigantic work crews. Slavoj Žižek, in Less Than Nothing, describes the classification approach the Soviets took to determine peasant friends from enemies:

In their attempt to account for their effort to crush the peasants' resistance in "scientific" Marxist terms, they divided peasants into three categories (classes ): bednyaki, the "miserable ones;' the poor peasants (no land or minimal land, working for others) , natural allies of the workers; serednyaki, the "middle ones;' the autonomous middle peasants (owning land, but not employing others), rich but oscillating between the exploited and exploiters; and "kulaks" (kulaki) who, apart from employing other workers to work on their land, were also lending them money or seeds, etc.—they were the exploiters proper, the "class enemy"—which, as such, has to be "liquidated." However, in practice, this classification became more and more blurred and inoperative: in the generalized poverty, clear criteria no longer applied, and peasants in the other two categories often joined kulaks in their resistance to forced collectivization. An additional category was thus introduced, that of a "subkulak," a peasant who, although too poor to be considered a kulak proper, nonetheless shared the kulak "counterrevolutionary" attitude. (p.72-3)

A Soviet crusade was launched to stop the peasants from producing for local markets. They would then be forced, on pain of starvation, to produce for the state. The tragic results of this policy are described by Robert Conquest, in Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror Famine:

The best and hardest workers of the land are being taken away’ (with misfits and lazybones staying behind) (p. 134)

Another modern Soviet author has written of collectivization in Siberia: the best peasants are deliberately wiped out; a rabble of loafers, windbags and demagogues come to the top; and any strong personality is persecuted regardless of social background. (p. 122)

Peasants who were not summarily executed on their farms were sent to Siberia. But even here the Soviets fought a ruthless battle against individual initiative and hard work. Even after deportation to Siberia, the Soviets found out they couldn’t keep a good kulak down:

In general, without horses or ploughs, with a few axes and shovels, the toughest of the deported peasantry survived and created fairly prosperous settlements - from which they were again evicted when the authorities noticed their growth. It is reported that one group of Old Believers even managed to set up a thriving settlement out of contact with the world until 1950, only to be discovered then and charged with sabotage. (p. 141)

Lenin and Stalin had closely read Marx and clearly understood that they were taking power in a backwards nation that had little capitalist infrastructure on which to build communism. Although the Soviet Union experienced outward success in creating an industrial base, the self-destruction of their small business market economy doomed the USSR’s system to failure. Perhaps this bad Soviet example of casting capitalism opened the eyes of the other giant Marxist society?

Forging Capitalism in China—The Return of Braudel’s Market Economy

Mao repeated the Soviet errors and the resulting famines were even more cataclysmic. After his death, Deng Xiaoping rose to power and slowly opened towards a market economy:

Beginning in 1979, Deng set up special economic zones (SEZ), essentially ring-fenced areas where capitalism could be practised in isolation from the rest of the communist country.

In their book, How China Became Capitalist, Ning Wang and Ronald Coase explain that China returned towards Marx's ideas:

First and foremost, the Special Economic Zones were intended to “appropriate capitalism for the good of socialism.” After visits to Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore, Japan, the United States, and Western Europe in 1978 and 1979, Chinese officials had been shocked by the astonishing technological advancement and economic efficiency achieved by the capitalist system and the pleasant living conditions enjoyed by the middle classes. They were forced to appreciate the extraordinary strength of capitalism in innovation, technological as well as institutional, a point actually made a long time ago by Marx himself. Chinese leaders no longer doubted that China’s pursuit of socialism could learn a lot from capitalism. (p. 62)

Wang and Coase describe four “marginal revolutions” that sparked China’s economic revival:

agriculture decollectivization and a return to private farming.

rural industrialization, mainly led by the rise of township and village enterprises.

“individual economy” of returned urban youth creating small businesses.

development of Shenzhen and the other Special Economic Zones.

China’s subsequent economic success sprang from this reincarnated small business sector. It’s no surprise that China would master this sort of economy. Adam Smith hailed the 18th century Chinese small market economy as the ideal example of what European economies should strive for back then. The European concept of laissez-faire derives from the pre-capitalist Chinese concept of wu-wei, which would translate as “active-inaction.”

While “main street” is mythicized in the US, in China small business is actually protected from the worst ravages of big box capitalism. Activists who search fruitlessly for an alternative need look no further than Braudel’s modest market economy of rural farms, production and urban small business. It is in this smaller realm that common-sense critics will find the misnamed capitalism they so worship.

Karl Marx was wrong to associate markets so strongly with capitalism. While markets are a necessary condition for capitalism to emerge, they pre-date it by centuries. And Adam Smith who while sacralising markets, expressed great scepticism towards high profits. This heresy alone disqualifies him from the capitalist club:

In Smith, profits should be low and labor wages high, legislation in favor of the worker is “always just and equitable,” land should be distributed widely and evenly, inheritance laws should partition fortunes, taxation can be high if it is equitable, and the science of the legislator is necessary to thwart rentiers and manipulators.

The modest market layer from Braudel’s triad is the economic ore from which leaders can forge capitalism. In turn—following the axiom that impure capitalism can be refined towards communism—Marxism aspires to add an economically equitable fourth level to the Braudillian model. The jury remains out on how that will progress. For many, Braudel’s market economy remains the true realm of justice.