Elon Musk: Pseudo-State Unleashed?

While the Deep State operates covertly within the government, and Pseudo-State entities—Soros, Gates, Bezos—act overtly outside it, both face an existential threat: Elon Musk's rise to power.

Elon Musk’s rapid ascent as a key force fronting the Trump 2.0 administration has prompted unusual alarm, especially among progressives, regarding the rise of oligarchic influence in the U.S. Yet Musk’s consolidation of oligarchic power is not without precedent. George Soros, through his Open Society Foundations and a network of NGOs, has long operated as a quasi-Justice Department, advancing “racial justice” agendas that often destabilize urban law and order. Internationally, Soros proxies have acted as a pseudo-CIA, executing regime changes under the guise of “Colour Revolutions” in Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan. His latest intervention unfolds in Georgia, where recent elections failed to produce Western-compliant leadership.

Similarly, Bill Gates leveraged the Gates Foundation during the COVID-19 pandemic to assume the role of a global health minister, directing vaccine distribution and shaping international health policy. Jeff Bezos, through Amazon, has transformed labor norms, logistics infrastructure, and local economies, creating a regulatory ecosystem that rivals or circumvents state oversight.

Such figures and their organizations epitomize the "Pseudo-State," a network of external entities wielding significant authority over domestic and international governance without constitutional or democratic accountability. Unlike the Deep State, rooted in bureaucracy, or the Surface State, represented by elected officials, the Pseudo-State operates from the periphery, mimicking state functions while existing beyond the formal bounds of state power.

Enter Musk

Not content with running a pseudo-NASA, Elon Musk’s close alignment with President-elect Donald Trump positions him to exert unparalleled influence over domestic and foreign policy. Musk’s ventures, including Starlink and SpaceX, increasingly blur the boundary between private enterprise and state functions. By embedding himself within the formal state apparatus, Musk is poised to shape U.S. space policy, global communications, military logistics, and a wide spectrum of other governmental priorities.

Trump’s appointment of Musk to chair the newly formed Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) commission underscores this shift. Tasked with identifying bureaucratic redundancies, DOGE provides Musk a potent tool to dismantle deep state elements resistant to his vision. While Musk’s prominence makes him the most visible exemplar, his rise is emblematic of a broader trend: oligarchs asserting sovereign-like authority without democratic accountability.

While the covert operations of the deep state attract scrutiny, the overt influence of pseudo-state actors, often aligned with progressive causes, is less examined. For years, criticism from the left has selectively targeted “unsavory billionaires” like Peter Thiel and Musk while lauding “benevolent billionaires” such as Soros, Gates, and Bezos as champions of noble causes. This dynamic creates a blind spot, allowing pseudo-state entities to thrive with minimal pushback.

The deep state has historically collaborated with pseudo-state organizations to maintain surface state compliance, advancing agendas on issues like Ukraine, COVID-19, mass immigration, and unwavering support for Israel. However, the rise of Musk and other “unsavory” oligarchs threatens this equilibrium. As these actors penetrate the surface state, deep state operatives may face a stark choice: align with these emerging powers or risk neutralization through initiatives like the DOGE commission or targeted lawfare campaigns.

Genealogy of the Pseudo-State

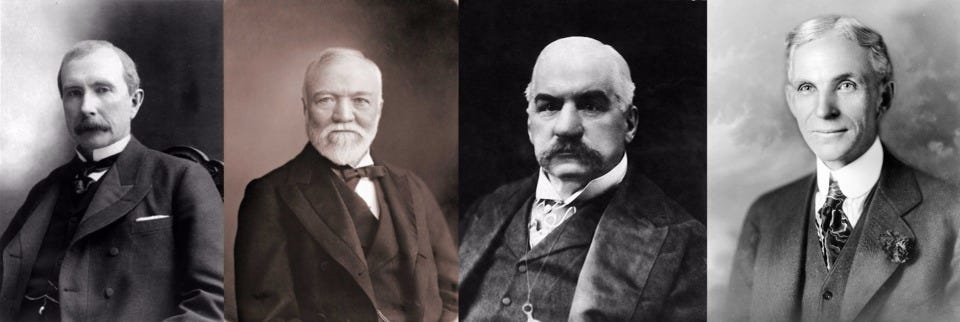

The emergence of pseudo-state entities can be traced to the early 20th century when industrial titans like Henry Ford and John D. Rockefeller established foundations that redefined the relationship between private power and public governance. These entities sought to influence policy, shape societal priorities, and assume quasi-governmental roles in areas traditionally overseen by the state. The Rockefeller Foundation, for example, became a pseudo-ministry of health by funding global health initiatives, such as combating malaria and yellow fever, wielding transnational influence that often rivalled national governments. Similarly, the Ford Foundation shaped educational and cultural policies, funding programs that aligned with its vision of progress and subtly steering public institutions.

Andrew Carnegie’s philanthropic ventures further exemplify the pseudo-state model. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace emerged as a significant player in global diplomacy, paralleling foreign ministries. The Carnegie Institution for Science funded ground-breaking research, acting as a quasi-public research body akin to a national science foundation. Additionally, Carnegie’s establishment of over 2,500 public libraries transformed public education and literacy, fulfilling state-like responsibilities at a local level.

Beyond philanthropy, pseudo-state entities found expression in the financial realm. J.P. Morgan acted as a de facto central banker during the Panic of 1907, stabilizing the economy in a manner that inspired the creation of the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve itself operates as a quintessential pseudo-state entity—blending public and private features, performing essential state functions like monetary policy, yet maintaining significant independence and opacity.

It is crucial to distinguish pseudo-state entities from non-state actors. Non-state actors—such as lobbying firms, advocacy groups, and activist organizations—are transactional tools often leveraged by state power. Their goals are narrow and operate within the state framework, seeking concessions or adjustments rather than fundamentally reshaping the system. Pseudo-state entities, by contrast, carve out areas of sovereignty by mimicking state roles, wielding power and authority that bypass democratic accountability and constitutional processes, reshaping governance from outside the formal state apparatus.

Pseudo-State on Steroids?

During this election cycle, Elon Musk donated a relatively modest $118 million to the Trump campaign and the broader GOP efforts. Yet, for this small investment, Musk saw a significant return—perhaps temporarily—with a $70 billion increase in his total wealth. Considering that the overall cost of funding the Republican Party is around $2.4 billion ($1 billion for Trump, $1.4 billion for Senate and House races), in the future, Musk could easily serve as the sole financier of the GOP, provided he navigates the relatively lax campaign finance laws. Relying solely on Musk's deep pockets would allow the GOP to break free from traditional funding sources like Big Pharma, the Military-Industrial Complex, woke corporate America, Wall Street, pro-Israel oligarchs, AIPAC and the Chamber of Commerce. With these entities already heavily aligned with the Democratic Party—Harris raised $1.6 billion in donations—such financial independence could enable the GOP to embrace more populist positions.

Musk’s financial resources, combined with government "efficiency" programs, could serve as potent tools in a prolonged campaign against the entrenched deep state. Should a future Republican Party headed by JD Vance, decide to pursue such a path—and while reasons exist to doubt their willingness—a direct confrontation with both the donor class and the deep state becomes feasible with Musk's backing. Such a campaign would embody aristo-populism, a political dynamic where segments of the oligarchy align with the general populace. This aligns with Aristotle’s concept of the ideal polity, a synthesis of democracy and aristocracy.

Historical parallels reinforce the fragility of such alliances. Julius Caesar, for instance, sought to establish a similar fusion of oligarchic power and popular support. However, his populist reforms and consolidation of authority provoked fierce opposition from rival aristocrats, culminating in his assassination. Musk will need to reinforce his personal security, perhaps with Palanitir Technologies playing the role of a pseudo-Secret Service, before launching any such scorched earth campaign against the current power structure.

Founded by oligarchs Peter Thiel and Kamala Harris donor Alex Karp, Palantir Technologies already functions as a pseudo-state entity by taking over roles traditionally reserved for state institutions like the FBI and the Department of Defense. Through its proprietary software platforms, Foundry and Gotham, Palantir integrates vast amounts of data to provide actionable intelligence for counter-terrorism, law enforcement, and military operations. Its tools are used by agencies to track patterns, uncover networks, and predict potential threats, effectively serving as an outsourced brain for state security apparatuses. Vice President-elect JD Vance has deep connections to Palantir.

Pseudo-State as Enigma

The ambiguous nature of the Pseudo-State resembles that of a pseudonym. It is a mask that reveals as much as it conceals, a name that dances on the threshold between presence and absence. It both exists and does not, carrying the weight of identity without anchoring itself fully to the person behind it. Its essence is chimerical, inviting double readings: is it a disguise, a new self, or both? Like the famous vase/ facial profile optical illusion, it shifts depending on the gaze—now solid, now spectral, always hovering between what is and what could be. The pseudonym lives in the liminal, never quite one thing or the other, a ghostly signature inscribed on the air.

The pseudo-state flickers between forms, its contours shaped as much by perception as by reality. At one moment, SpaceX is a private enterprise—bold, entrepreneurial, independent; at another, it morphs into a new NASA, shouldering ambitions to colonize Mars. Its vast satellite network could be a revolutionary private communications infrastructure—or the national security state’s omnipresent tool for surveillance. The pseudo-state thrives in this liminal space, elusive and amorphous. It claims independence but cannot fully detach, existing as both an extension and shadow of the formal state.

This shape-shifting nature is not merely confounding but strategically evasive. The pseudo-state privatizes triumphs while socializing failures. When SpaceX achieves orbital milestones, it is heralded as a beacon of private ingenuity; when projects falter, the burden often shifts to the government safety net. Similarly, Gates’ vaccination campaigns are lauded when successful, yet public backlash over inequities or missteps is directed at the state. This duality allows the pseudo-state to harness its ambiguous existence: an independent innovator when convenient, an intertwined partner when advantageous. It reaps the rewards of its successes, deflects the risks of its failures, and cements its dominance in the precarious interplay of sovereignty.

The Return of Feudalism?

The pseudo-state phenomenon echoes the fragmented sovereignty of medieval feudalism, where power was dispersed among kings, lords, knights, and the Church, each wielding authority within distinct domains. Similarly, today’s pseudo-states claim sovereignty over specialized spheres—health (Gates), regime change operations and racial justice reform (Soros), and space exploration (Musk)—bypassing traditional state control. Feudal lords derived power from land and loyalty, while pseudo-states leverage wealth, technology, and transnational networks, operating on a global scale. Unlike feudal fragmentation, which was legitimized by shared cultural frameworks, pseudo-states often challenge state legitimacy itself, positioning their actions as corrections to state failures.

While pseudo-states offer efficiency and innovation absent in bureaucratic states often staffed by intellectual midwits, their unaccountable power presents profound risks. For libertarians and anarchists, these entities might seem a welcome decentralization of oppressive state power. However, when pseudo-states replicate or amplify harmful functions—mass surveillance, war-making, or public health manipulation—they may exacerbate, not mitigate, systemic abuses. Detached from democratic accountability, their motives are shaped by institutional self-interest, creating a paradox where their capability amplifies both their potential benefits and their dangers.

Trump 2.0: Napoleon III or Bismarck?

Louis Napoleon III and Otto von Bismarck are two figures emblematic of mid-19th century European statecraft, yet their approaches and legacies differ starkly. Marx’s famous quip that history repeats itself, “first as tragedy, then as farce,” was directed at Louis Napoleon, whose ascent as Emperor of France he saw as a comical echo of his uncle Napoleon Bonaparte’s grandeur. Napoleon III was an aristo-populist who leveraged his image as the "man of the people" to gain and consolidate power, relying heavily on spectacle and propaganda. However, his reign was marked by erratic policies and mismanagement, culminating in the disastrous Franco-Prussian War of 1870, which cost France its dominance in Europe and led to his ignominious exile.

In contrast, Otto von Bismarck was a master strategist and statesman, wielding power with unparalleled pragmatism and vision. As the architect of German unification, he effectively navigated the complex web of European alliances and rivalries to forge the German Empire in 1871. While Bismarck's policies could be ruthless, he also pioneered the modern welfare state, instituting health insurance, accident insurance, and old-age pensions to undercut socialist movements and strengthen national unity.

Where Louis Napoleon exemplified the pitfalls of populism and personalism, Bismarck demonstrated the efficacy of calculated, institutionalized power. His legacy stands as a testament to the transformative potential of statecraft, contrasting sharply with the farcical and ultimately tragic reign of Louis Napoleon III.

For three decades, the Western world has been dominated by a globalist elite—socially liberal, economically conservative, and aggressively interventionist in foreign policy. Donald Trump, borrowing from Marine Le Pen’s playbook in France, disrupted this paradigm by running as a social conservative, economic populist, and America First non-interventionist. Yet, during his first term, Trump’s ambitions were thwarted by a deep state and pseudo-state alliance, reducing his presidency to a spectacle reminiscent of Louis Napoleon III’s erratic rule.

Powerful nation-states are often tempted by colonial adventures. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the emergence of the U.S. unipolar moment, American elites have prioritized managing the chaotic international system over domestic concerns. This quest for global hegemony has demanded sacrifices at home, as America’s own needs are side-lined for imperial ambition.

Trump’s base, however, craves a leader like Bismarck, not Napoleon III. They are now willing to gamble on Elon Musk, hoping he can weaponize his version of the pseudo-state against the entrenched globalist nexus of deep and pseudo-state actors. Perhaps Musk’s ambitions to colonize Mars could redirect American imperial energies into a less destructive outlet, offering a new, safer frontier for its hubris.

It seems to me that the keys to controlling either State or private oligarchs rests with transparency from within and without. Use of FOOA lawsuits and the 1st Amendment

Please hit the like button at the top or bottom of this page to like this entry. Use the share and/or re-stack buttons to share this entry across social media. Leave a comment if you have anything to add.

And don't forget to subscribe if you haven't done so already.