Collapsing Narratives

China is simultaneously a collapsing economic basket-case and a long-term strategic challenge. Is China a paper dragon or is it time to send in the dragon slayers?

Late summer, after a major Chinese bank failed, there were a rash of “China’s about to Collapse” videos. At the same time American military and political leaders were sounding alarm bells over future Chinese global power. The US began pressuring Europe to sanction and cut ties with the Communist regime in Beijing but were met with stiff EU resistance. Today while the Chinese economy is indeed suffering credit problems, China is looking forward to 5% growth in 2023. On April 20th, President Xi will travel to Moscow to sign agreements with President Putin. They will perhaps formalize what is already a powerful anti-hegemonic alliance aimed directly at ousting the US from her current position as global leader.

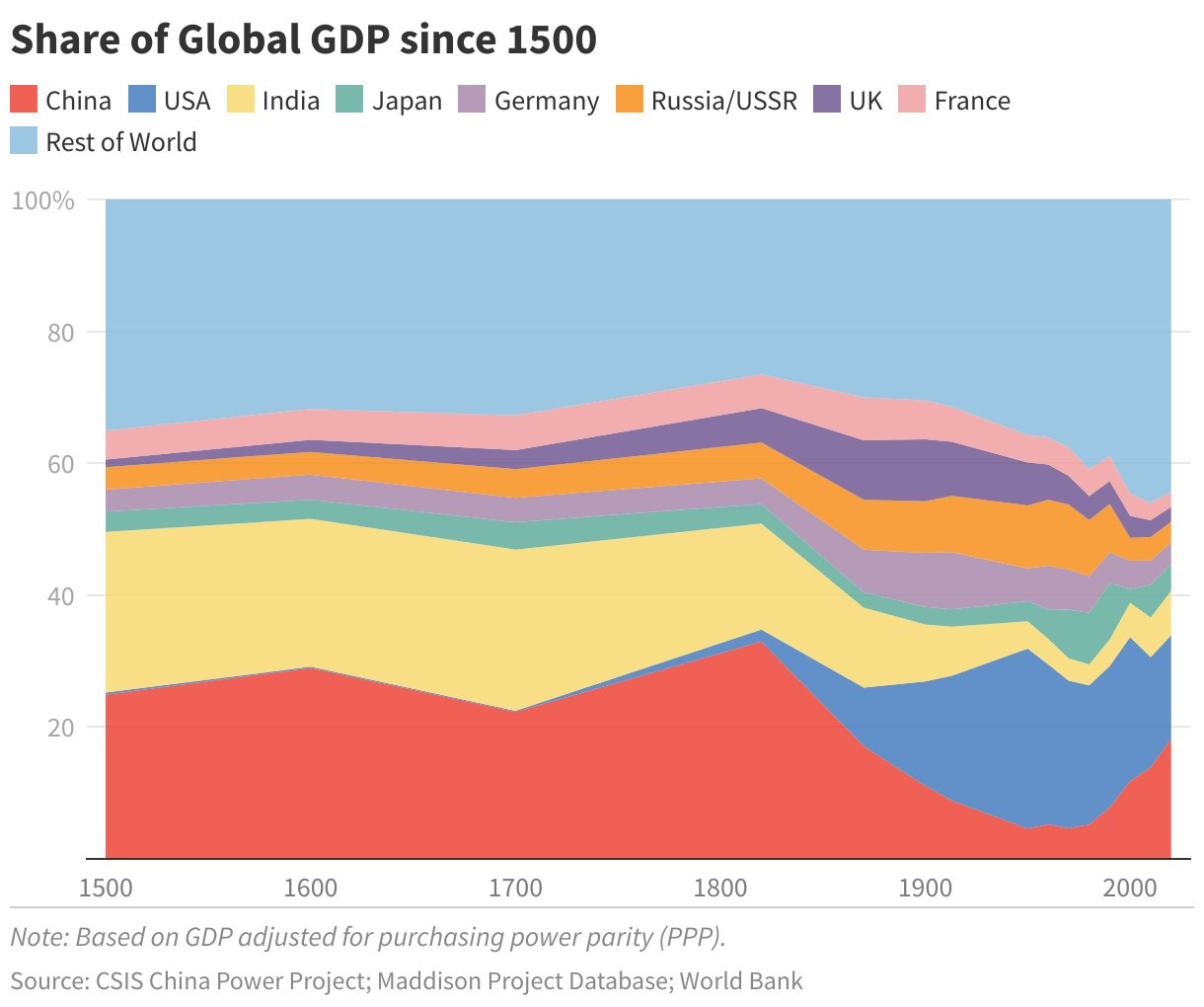

Historically, for 300 out of 500 years of the Modern period, China had the highest GDP (PPP basis) in the world. But clearly around 1800, a collapse did occur which was only righted towards the end the 1970’s:

At the dawn of the 19th century, economic development in Europe and China was roughly equal. Even comparing the leading areas, the Yangtze Delta area around Shanghai and England were comparable in most economic comparisons. Adam Smith thought the 18th century Chinese economy was an ideal example for what Europe should be aiming for. The European economic concept of laissez-faire derives from the Chinese concept of wu-wei, which would translate as “active-inaction.”

But where China and Europe were far from equal was in military capabilities and their ideas concerning its proper deployment. Starting with the First Opium War in 1839, England demanded, with increasing levels of force, that China buy her machine-made products. For centuries previously the West had been sending gold to China to purchase fine luxury goods. The West had nothing to sell China, and so the West’s gold reserves were being depleted. Britain decided that China would accept opium produced in India in return for her goods, thus keeping Britain’s gold in London.

The Chinese disagreed and so British business, backed by the British Navy, refused to take no for an answer. This combination of State/Business was unknown in China, where business organizations were small and the State only played a regulatory role. China’s approach was that of a more simple market economy. Britain had for centuries the state’s warships do the dirty work for British business enterprises. Britain was following a capitalist logic in combining business enterprises with state military might.

In the Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx relegates the military aspects of this Britain/China conflict to the metaphoric level, as he triumphally celebrates the capitalist destruction wrought on the market economy of Qing China:

The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilization. The cheap prices of its commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians' intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate. It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilization into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.

Looking back, we can see an ironic cyclical pattern between China and the West. Back in the early days of capitalist global penetration--fuelled by the Industrial Revolution and its labour-saving machines--it was cheap English goods, backed by British military might, which were destroying Chinese jobs. According to Friedrich Engels, “(China) bought the cheaper commodities of the English and allowed their own manufacturing workers to be ruined.” He added “we have come to the point where a new machine invented in England deprives millions of Chinese workers of their livelihood within a year’s time.” The capitalist destruction that Karl Marx cheered in 1848, only in mirror image in the industrial heartland of the US, is what led to the rise of Trumpism manifested in a desire for protective walls. The major difference is that China does not (yet) resort to military means to open US markets. The US financial elite and their media hacks are the heavy artillery that batters down US worker resistance to cheap Chinese commodities.

After Mao spent two decades misunderstanding Marxism by imaging that communism was some sort of alternative to capitalism, Deng Xiaoping came to power in 1976. His “market reforms” were evidence that he actually understood that socialism/communism can only be reached after passing through the capitalist stage. And since then the Chinese economy has been rising, which in turn has driven a plethora of “China Collapse” narratives from Western intellectuals.

In 1994, President Clinton reversed his campaign promises and once again gave China “Most-Favoured-Nation” trading status, five years after the events in Tiananmen Square. This move was controversial and as if in order to quell any fears of China eventually taking over the world, a wave of China Collapse narratives was unleashed. In 1995 Foreign Policy published article entitled, “The Coming Chinese Collapse” by Harvard educated scholar Jack A. Goldstone. This article was published within the memory of the collapse of the Soviet Union and so the eventual collapse of a Communist regime certainly seemed like a reasonable hypothesis at the time:

In sum, China shows every sign of a country approaching crisis: burgeoning population and mass migration amid faltering agricultural production and worker and peasant discontent-and all as the state rapidly loses its capacity to rule effectively.

<…>

Dynastic collapse in China has always been heralded by fiscal decay at the center, conflicts among elites, and the rise of banditry and warlordism along the periphery. Population pressures have created these conditions and undermined Chinese dynasties in the past; latest "dynasty" appears unlikely to break with these historical patterns.

In October of 2000, China had not yet collapsed and so President Clinton signed the United States–China Relations Act of 2000 which granted China WTO status and granted the permanent Normal Trade Relations. Since capital seeks profit like a drunk seeks whiskey, American business needed guarantees that their desire to dismantle American factories and ship them to China would not be blocked by future trade problems.

Again, fears of a eventual Chinese economic colossus were growing. In 2001, economist Gordan Chang authored, The Coming Collapse of China:

The end of the modern Chinese state is near. The People's Republic has five years, perhaps ten, before it falls. This book tells why.

<…>

On paper, China looks powerful and dynamic even today, less than twenty-five years after Deng Xiaoping began to open his country to the outside world. In reality, however, the Middle Kingdom, as it once called itself, is a paper dragon. Peer beneath the surface, and there is a weak China, one that is in long-term decline and even on the verge of collapse. The symptoms of decay are to be seen everywhere.

<…>

As time passes, the underlying problems fester. Economic dislocations become social ones, with dark political overtones. At some point there will be no solution. Then the economy, and the government, will collapse. We are not far from that time.

Chang made the classic mistake, repeated by so many apocalyptic doomsayers in giving too precise a date—2011--for the expected collapse. When 2011 rolled around and the Communist Party was still piloting the rocketing Chinese economy, Chang doubled down and promised the collapse would happen in 2012. To his credit, Chang did sell a lot of books. And whether intentionally or not, he gave cover to US business leaders who sent US factories or capital to Beijing after being reassured that the Communist Party would fall and a US-friendly regime would take over.

Today even the CIA admits that today China has the largest economy in the world. China makes up nearly 19% of GDP (PPP basis) while the US has fallen to 15%. PPP (Purchasing Price Parity) is a method of comparing national GDP’s by balancing unequal pricing. If a dozen eggs costs $4 in the US but only $1 in China, a factor is employed to determine the true size of the cheaper priced economy.

Of course, China has more than three times as many people as does the US so China has a long way to go to catch up on per capita GDP (PPP basis).

And so recently there have again been a rash of China-doomers predicting the regime would collapse in 25-29 days. Since then President Xi has signed deals with Saudi Arabia and has important visits to Iran and Russia agreed in the coming months.

Geopolitical analyst Peter Zeihan has a long track record of making failed China collapse predictions. His predictions of a Chinese credit collapse back in 2005 never materialized. He doubled-down in 2010 when he predicted:

<…> I would say we expect the economic collapse of China in this coming decade. We've been talking for awhile about how the economic system there is remarkably unstable and we think that they're going to reach a break point as all of the internal inconsistencies come to light and shatter. By the end of the decade, it'll be pretty obvious to everybody that the China miracle is over. As we enter the decade, people are finally, finally starting to talk about China bubbles. If only their problem was that simple!

China did not collapse and so recently Zeihan was on the Joe Rogan Show and again preached his China Collapse Gospel and gave himself an additional ten years before his predictions can be falsified. It is frustrating to fact-check Zeihan because so many of his claims are wrong that it is painful even listen to them. Here is one site that took the time to debunk his claims. One huge red flag for me was his claim that Mao instituted the One-Child policy: “Mao was concerned that as the country was modernizing, the birth-rate wasn’t dropping fast enough, and the young generation was literally going to eat the country alive.” In fact the opposite is true, Mao encouraged large families right up until his death in 1976. It was in 1980 under Deng Xiaoping that the One-Child policy became law. From the Guardian:

In China, procreation and childbirth are, like every facet of human life, deeply political. Since the Communist party came to power in 1949, it has viewed the country's population as a faceless number that it can increase or decrease as it chooses, not a society of individuals with unique desires and inviolable rights. At first, Mao Zedong encouraged large families and outlawed abortion and the use of contraception, urging women to produce offspring who would boost the workforce and the ranks of the People's Liberation Army. My mother dutifully gave birth to five children. Our neighbour, Mrs Wang, produced 11, and was declared a "Heroine Mother" by the local authorities and given a large red rosette to pin to her lapel.

Mao's reckless strategy caused China's population to double from about 500 million in 1949 to almost a billion three decades later. By the time Deng Xiaoping took over the reins in 1978 after the calamitous cultural revolution, not only was Mao dead, but so was all faith in communist ideology. Deng knew that for the party to regain legitimacy, it would have to achieve economic growth, and a small group of technocrats, headed by rocket scientist Song Jian, persuaded him that for China to meet its economic targets for the year 2000, its population would have to be restricted to 1.2 billion. The one-child policy they proposed was swiftly introduced: couples in China could have only one child, or in the countryside two if the first child was a girl. The production of children became as subject to state targets and quotas as the production of grain and steel.

Claiming Mao introduced the One-Child Policy is as mistaken as saying he introduced market reforms. It is to completely misunderstand recent Chinese history. Mao was a general and thought in terms of armies and manpower. He was not exactly an economic genius, which is why China’s ascendency only started after his death.

Clearly China, more than most nations, faces some incredibly difficult economic challenges going forward. The doomsday videos do bring up potential issues for the Chinese economy: dependence on imported food; real estate “Keynesianism” and the need to diversify fiscal stimulus away from construction; the transition from a low-income economy towards a becoming a high-income fully developed nation; intensifying the crackdown on wealthy bankers and oligarchs, and transitioning away from the dollar. However narratives of imminent Chinese collapse are repeatedly demolished like so many unfinished high-rises in China’s many ghost cities:

While demolition videos do demonstrate China’s rampant policies of malinvestment in construction, these very visible Chinese losses must be compared to the estimated $8 trillion in loses the US suffered in their war against Iraq and Afghanistan.

Just yesterday, Iraq and China signed a deal to conduct trade in the Chinese Yuan. This deal does not include oil China and Iraq already have an "oil for infrastructure" barter deal where Iraq ships three million barrels a month to China and in return China builds infrastructure projects. So oil between China and Iraq is already being traded outside the dollar. There were persistent rumours back at the time of the Iraq Invasion, that the “real” reason was that Saddam Hussein was selling Iraq’s oil in Euros. If so then the US didn’t get much for her $8 trillion investment.

The truth is that Communist China is a fascinating subject for anyone interested in macro-economics. My preferred source of information on China’s economic misadventures is Michael Pettis. He is highly critical of many of China’s economic choices yet his motivation seems more rooted in economic reality than in highlighting easily digested narratives.

But the most bizarre aspect of these “China is vulnerable” slogans is their glaring narrative clash went compared to those of the US national security establishment, who have determined that China is the sole threat to US dominance:

"The [People's Republic of China] is the only competitor out there with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, a power to do so," Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin told reporters Thursday at the Pentagon.

A senior defense official, speaking to reporters about the new defense strategy on the condition of anonymity, said China continues to gain more "capability to systematically challenge the United States across the board: militarily, economically, technologically, diplomatically."

Given both the long-term and short-term trends, the warnings for the national security state carry much more weight than the wishful thinking of a Chinese economic collapse. Time will tell. There is no doubt that at some point as China climbs towards the height of global power that her economy will go necessarily through some major realignments.