Climate Regime Change

A small proposal for a climate change Reformation.

Climates change. A fixed, steady-state climate is nonsense. The concept of climate change has no explanatory power and no possible solution.

Our climate is the result of three forms of motion. High and low pressure systems swirl in the atmosphere as our globe simultaneously spins on its tilted axis and rotates around a powerful sun. Such a dynamic system leaves little hope for metrological fixity.

The everchanging coming and going of meteorological events (storms, heat waves) during a year form seasonal patterns. When combined with annual variations, these three elements form a climate. Long-term climatic temperature trends bounce up and down in a roughly 100,000 year cycle, within a band of ice ages (glacial) and warming periods (interglacial). Arresting these dynamic movements can only occur with the death of our universe.

Adding the qualifier “man-made” to “climate change” suggests its antithesis: “natural climate change.” Setting aside the absurdity of human activity occurring outside of a natural context, the question now becomes one of agency. We suspect from ancient ice bores that the climate has “changed” since time immemorial. Evolution theorizes that humans didn’t even exist during much of this period, let alone have the technical means to impact the climate. Solar fluctuations, earthly orbital changes, volcanic activity and oceanic current patterns all play their part in the great climatic churn.

Nevertheless we also know that since the industrial revolution, the system of capitalism:

has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together. Subjection of Nature’s forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam-navigation, railways, electric telegraphs, clearing of whole continents for cultivation, canalisation of rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground <…>.

Given man’s massive productive activities and newfound ability to reshape the earth, an initial hypothesis that man’s terrestrial activities are impacting the already existing trends of natural climate change is plausible. Carbon dioxide is known to impact atmospheric temperatures and the American cycle of capitalism was fuelled by fossilized hydrocarbons, which when burnt release CO2.

Unpacking the ratio of man-made to natural climate change will be difficult. While the man-made impact can be assumed to be pushing towards warming, what direction is today’s natural tendency moving? These investigations are similar to the nature vs. nurture debates about the relative importance of natural genetic inheritance versus man-made environmental impacts on the human organism. An extreme position would be that the climate is a “blank slate” and that all changes are due to human activity. The other extreme would be an essentialist view that all climate change is natural, if we accept the notion that man is somehow unnatural. Reality must exist somewhere between these two poles.

Empirical science

“Science” comes in two forms. Empirical science studies observable phenomenon and proposes explanatory hypotheses. Experiments follow which attempt to falsify these hypotheses, or to replicate previous confirmatory experiments. Truth is never established, although a “good enough” truth may be approached as hypotheses evolve towards being ever more difficult to falsify and easier to replicate.

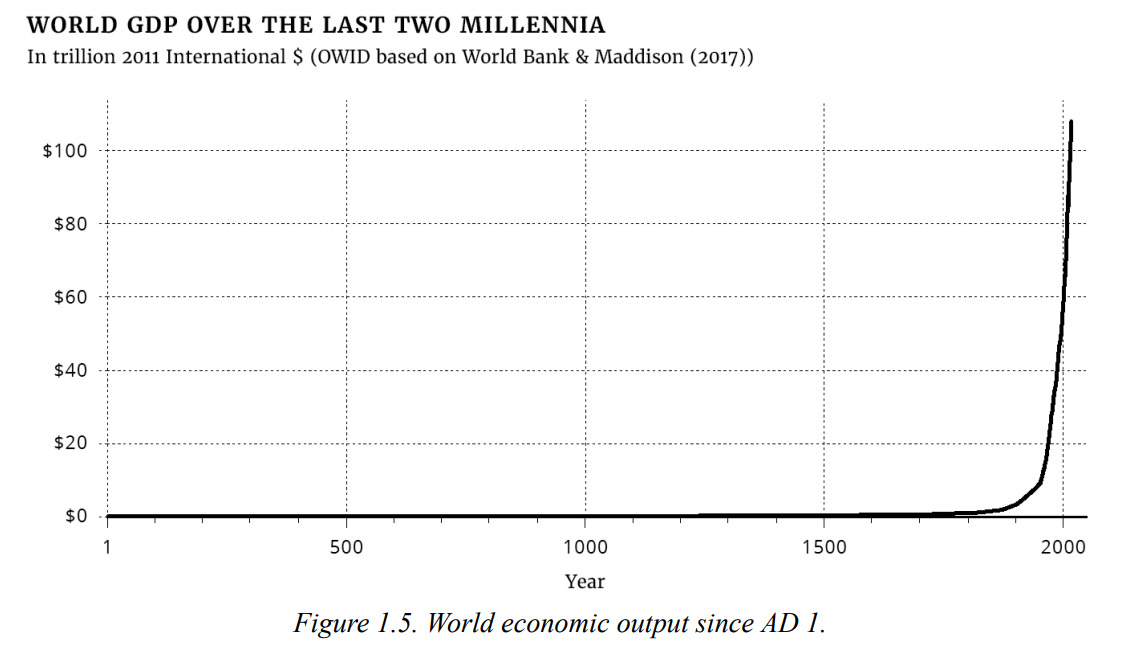

Empirical science thrives in a culture of critique where paradigms exist to be challenged and overthrown. It is the intellectual version of creative destruction. Just like a climate, nothing is fixed in empirical science. However, empirical science is a powerful tool of both technical advancement and environmental degradation. The near vertical leap in global GDP is mostly attributable to intellectual scientific advances leading to material technical innovation. Empirical science is a method of applying the power of doubt to produce tangible real-world results.

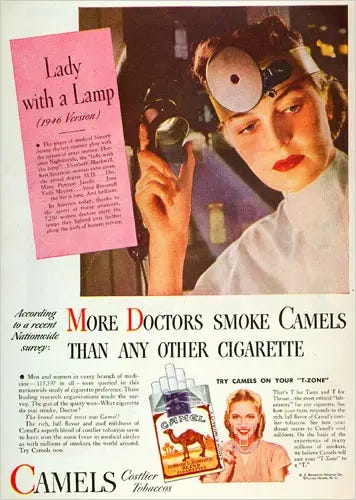

Empirical science, while great for fuelling incremental technological advances, is a slow and frustrating way to grapple with larger scale phenomena, like climate change. There is no “Yes” or “No” in empirical science, only varying degrees of Maybe. The link between cigarette smoking and cancer is an example. For much of the 20th century, the American ruling class tried to convince consumers that constantly inhaling tobacco smoke was good for them. To do so the narrative power of “Science” was employed to boost cigarette sales.

Afterwards tobacco multinationals attempted to manipulate empirical science. But “proving” cigarette smoking caused cancer was a steep hurdle and so continuing to smoke while waiting for empirical science to have its say was not the best strategy for consumers to follow.

Narrative Über Alles: Metaphysical Science

To quench our desire for cosmic order and certainty is why human nature craves religion in all its forms. But since overt traditional religious belief has become anathema to sophisticated Western ruling classes, a more “rational” secular—but equally dogmatic—substitute is conjured.

Metaphysical “Science” steps in as a quasi-religious form of discourse which makes claims to transcendent truth by covering self-serving narratives with the mask of empirical science. In the faith vacuum created by the decline of traditional religious belief, modern secular societies—starving for the innate human need for certainty—fetishize metaphysical Science. Instead of an angry Father figure in the sky launching thunderbolts, metaphysical Science posits a kindly committee of earth-bound bespectacled scientific experts, issuing infallible edicts. Given their metaphysical nature, these Science Commandments must never be questioned. To ever attempt such a stunt is an act of heresy. Metaphysical Science insists on a culture of obedience towards a priestly class of experts.

Climate change has deformed into a heavily theologized Science, despite plenty of valuable work ongoing within the realm of empirical science. It has been captured and weaponized primarily by two forces: center-left bourgeois political parties and giant multinational corporations. It’s vital to point out that fighting against metaphysical Science does not invalidate actual science happening on the empirical level. One can fight the politicized version of climate change Science independent of any claims to empirical scientific validity.

The political nature of climate change is revealed in its uneven application. When useful as a tool of class oppression like stripping property from the masses, climate emergency narratives are deployed. But at the drop of a geopolitical hat, the War Party rises to the fore and pushes the apocalyptic climate emergency into the recesses. For example in Ukraine, given the posited existential climate threat we are facing, the Minsk 2 agreement should have been renamed the Save Our Planet agreement and enthusiastically endorsed. Instead geopolitical expansion was prioritized and war resulted. Recently a half a billion dollars worth of Western ammunition, including depleted uranium shells were destroyed by Russian drones, causing an environmental disaster. The Green Party in Germany cynically fires up coal burning plants to power electric vehicles in an attempt to punish Russia. Seymour Hersh accuses Jake Sullivan of leading the political team that ordered the Nord Stream ecological disaster. Meanwhile the World Economic Forum plots climate austerity against the larger population.

Metaphysical Science starts with a narrative goal and then proceeds to manufacture empirical science to validate it. The classic example is the Geocentric model of the universe which was driven by Biblical anthropocentrism. When Copernicus demonstrated a heliocentric model, he was attacked not for sloppy empirical science but for undermining the sacred narrative of humans being the center of the universe.

The metaphysical Science of climate change is the perfect religious vehicle for secular Western ruling classes to satisfy their spiritual needs while reinforcing their elite positions within the social hierarchy. Traditional religions look skyward and posit imaginary “friends in the sky.” Instead of residing in fallen man’s hearts, in climate change, mankind’s depravity floats upward in the form of carbon dioxide. Lifted from the underworld, hell burns bright above us. In a secular inversion, the gods of climate salvation (CEOs of multinationals, center-left politicians) are earthbound in their boardrooms or on the campaign trail.

Apocalyptic messaging projects the looming disaster of climate change onto a near-future event horizon (the doomsday clock is ticking…) and is intended to provoke fear in target audiences. Once in an emotional state, the masses are molded by the fearmongers. In response to this crude manipulation, there will always be a reactive impulse to simply deny the fear, even if it may be real. But this is part of the apocalyptic game. As more and more observers fall into the trap of emotionalism, fewer and fewer people are left to analyse the problems through critical lenses.

Metaphysical climate change proposes solutions which implicitly maintain continued infinite progressive economic growth. The only true solution to the hypothesized problem of environmental damage (including climate) is a form of steady-state circular growth.

While it is indeed true that up until today, every single apocalyptic projection announcing the end of the world has been completely wrong, this might be a result of survivorship bias. Necessarily only the very last doomsday projection will harken that fateful collective meeting with our maker. The more an apocalyptic projection confirms with empirical science, the more it will be effective in manufacturing its intended change. But the prophesies cannot be too specific. A “great disappointment” is created by projecting too clearly a doomsday event or date horizon. A clever doomsday narrative is vague enough to be impossible to falsify, and yet specific enough to motivate.

German sociologist Max Weber explains how ruling-class religious values differ markedly from those they impose on the ruled:

Religions of privileged ruling strata emphasize this-worldly values. Members of such strata feel intrinsically worthy because of their present social positions, and their religious beliefs justify the social system that allowed them such elevation. Members of underprivileged and oppressed strata, far from feeling worthy in terms of what they are, emphasize the importance of what they will become. They emphasize otherworldly values, and their religions depict a future salvation entailing a radical transformation of society's present relationships.

When facing a potential crisis, we must resist the all-too-human rush towards the emotional manipulations that metaphysical Science seeks to induce. A more subversive attitude would attempt to wrestle control of this new narrative-producing religion, all the while keeping an eye on actual empirical science. By highlighting the hypocrisy and magical thinking of our current climate priests, a sort of Reformation becomes possible to turn the tables of power against them.

Ecological Religion

Lynn Townsend White Jr, a professor of history who taught at Princeton, Stanford, Mills College and UCLA during his long career, became one of the founding fathers of the ecological movement with his 1967 essay, The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis. His thesis was that science is not the answer to the ecological crisis and that only a religious revolution will stop man from degrading his environment.

White states that at a fundamental level Christianity is responsible for the ecological crisis. Perhaps due to Cold War prudence, Professor White never mentions capitalism directly but he does elude to its doctrine of infinite growth in the religious realm:

The victory of Christianity over paganism was the greatest psychic revolution in the history of our culture. It has become fashionable today to say that, for better or worse, we live in "the post-Christian age." Certainly the forms of our thinking and language have largely ceased to be Christian, but to my eye the substance often remains amazingly akin to that of the past. Our daily habits of action, for example, are dominated by an implicit faith in perpetual progress which was unknown either to Greco- Roman antiquity or to the Orient. It is rooted in, and is indefensible apart from, Judeo-Christian teleology. The fact that Communists share it merely helps to show what can be demonstrated on many other grounds: that Marxism, like Islam, is a Judeo-Christian heresy. We continue today to live, as we have lived for about 1700 years, very largely in a context of Christian axioms.

White deplores the concepts of perpetual progress and centering man above nature, the very axioms that drive the current metaphysics of climate change. However White doesn’t place much hope in science either:

Science was traditionally aristocratic, speculative, intellectual in intent; technology was lower-class, empirical, action-oriented. The quite sudden fusion of these two, towards the middle of the 19th century, is surely related to the slightly prior and contemporary democratic revolutions which, by reducing social barriers, tended to assert a functional unity of brain and hand. Our ecologic crisis is the product of an emerging, entirely novel, democratic culture. The issue is whether a democratized world can survive its own implications. Presumably we cannot unless we rethink our axioms.

Environmental interventions are notoriously difficult and closely run operations. The problem of unintended consequences haunts even the most well-intentioned innovations. Humans intervening into the complex natural ecosystem is fraught with danger as our puny minds, fuelled by hubris, attempt God-like changes. Even an intervention such as electric vehicles, driven by smug urbanites, creates widespread environmental degradation in the periphery areas of the globe due to rare earths mining:

Rare earths are mined by digging vast open pits in the ground, which can contaminate the environment and disrupt ecosystems. When poorly regulated, mining can produce wastewater ponds filled with acids, heavy metals and radioactive material that might leak into groundwater. Processing the raw ore into a form useful to make magnets and other tech is a lengthy effort that takes large amounts of water and potentially toxic chemicals, and produces voluminous waste.

However, this is our fate and we cannot run away from it. There is a human duty to not degenerate the earth and nature. Although it was resisted by many 60 years ago, the achievements of the environmental movement are undeniable. Cleaner water and air, better natural habitats, etc. Everyone has a duty to keep an open mind to empirical scientific thinking on the question of environmentalism, which includes the climate. At the same time there is a social duty to fight the use of metaphysical Science as a tool to subjugate local populations.

White ends his essay with a plea for a religious approach to ecology:

Since the roots of our trouble are so largely religious, the remedy must also be essentially religious, whether we call it that or not. We must rethink and refeel our nature and destiny. The profoundly religious, but heretical, sense of the primitive Franciscans for the spiritual autonomy of all parts of nature may point a direction. I propose Francis as a patron saint for ecologists.

in 1979, Pope John Paul II proclaimed St. Francis of Assisi the patron saint of the environment. Not long afterwards, the global warming narrative, precursor to climate change, pushed ecology and environmentalism out of the media spotlight.

A Buddhist Economics of Ecology

In his 1973 work, Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered, economist E. F. Schumacher proposes Buddhist economics as an alternative to our current ecologically destructive path.

Schumacher starts with an attack on the “metaphysical blindness” of Western economics. Instead of realizing their work is religious justification of infinite production, they claim their economic doctrines are “a science of absolute and invariable truths without any presuppositions.” They are simply restatements of capitalist axioms.

Attitudes towards consumption mark a key difference between Western and Buddhist conceptions of economics:

While the materialist is mainly interested in goods, the Buddhist is mainly interested in liberation. <…> It is not wealth that stands in the way of liberation but the attachment to wealth; not the enjoyment of pleasurable things but the craving for them. For the modern economist this is very difficult to understand. He is used to measuring the 'standard of living' by the amount of annual consumption, assuming all the time that a man who consumes more is 'better off' than a man who consumes less.

High quality / low quantity consumption is both more pleasurable and more ecological than low quality / high quantity consumption that is so prevalent in the West. Local production intensifies the beneficial impact:

Simplicity and non-violence are obviously closely related. The optimal pattern of consumption, producing a high degree of human satisfaction by means of a relatively low rate of consumption, allows people to live without great pressure and strain and to fulfil the primary injunction of Buddhist teaching: 'Cease to do evil; try to do good.' As physical resources are everywhere limited, people satisfying their needs by means of a modest use of resources are obviously less likely to be at each other's throats than people depending upon a high rate of use. Equally, people who live in highly self-sufficient local communities are less likely to get involved in large-scale violence than people whose existence depends on world-wide systems of trade. From the point of view of Buddhist economics, therefore, production from local resources for local needs is the most rational way of economic life, while dependence on imports from afar and the consequent need to produce for export to unknown and distant peoples is highly uneconomic and justifiable only in exceptional cases and on a small scale.

Buddhist economics might on the surface seem exotic to Americans but a careful look at the history of early 19th century America will show that Thomas Jefferson’s economic policies track closely to these modest Buddhist ideas. Indeed, his great rival Alexander Hamilton’s capitalist policies can be directly blamed for the ecological / climate problems the world currently faces.

Thomas Jefferson’s Small Economy

An overt religious approach to the ecology question is preferable to one hiding behind the mask of science. This entails exposing the metaphysical nature of the chosen economic system as a deliberate choice, not the objective result of some imagined science. An alterative choice for ecological patron saint are Thomas Jefferson and his agrarian Democratic-Republican Party who battled Alexander Hamilton and his capitalist Federalist Party for the soul of America in the aftermath of the American Revolution.

In his paper, The Anticapitalist Origins of the United States, Michael Merrill summarizes the conflict:

In short, where the Federalists wanted to see the United States become a capitalist country, the Democratic Republicans were content to let it remain an agrarian one. This difference lay at the heart of their debate over economic policy in the first years after the Revolution. Federalists generally supported policies that put the interests of monied men and others dependent on the commercial economy before those of most farmers and artisans.

Merrill contrasts the starkly different class interests behind each political party:

The Federalists believed that if the United States was to survive and prosper, it needed to win the support of its wealthiest citizens and mobilize their resources on its behalf, as England had done. <…> The Democratic Republicans, on the other hand, believed that the mass of small property holders, the "middling sort," was a more important prop to the new republic than the rich Few. They rested their hopes on proposals designed both to strengthen local economies, which were based largely on barter, and to encourage the devolution or widespread distribution of property. They preferred a country in which many people had enough to live on and were free of the "casualties and caprices of customers" to one in which livelihoods depended upon whether a relatively small number of monied men had sufficient incentive to provide jobs for a large class of propertyless wage earners.

While Hamilton’s policies dominated George Washington’s two terms as President, in 1800, Thomas Jefferson changed paths:

The Democratic Republicans had other dreams. They envisioned an "empire of liberty" in the New World, where the blessings of free government could be enjoyed by independent farmers and artisans down to "the thousandth generation."

Another founding father explains the benefit of a small economy:

"The class of citizens who provide at once their own food and their own raiment," James Madison observed, "may be viewed as the most truly independent and happy.

An alternative history where Thomas Jefferson’s vision of an agrarian society triumphed, where the freed slaves had received their 40 acres and a mule, and this society continued into the present is yet to be written. Had American capitalism not developed post-Civil War, then climate change as theorized would not exist. No Fordism, no petroleum-based economy, no massive technological advances. It would be as if a time-traveller had gone back and killed baby climate change in the crib.

Of course, the Democratic Republicans were bucking the tide of history. They could delay the development of capitalism in the United States, but they could not prevent it altogether. First, they had no real power over the course of events in other areas of the world, especially in Europe, where capitalists ultimately succeeded in reorganizing the agricultural sector, creating a vast pool of propertyless laborers who were eager to work in U.S. factories.

Unfortunately that train left the station more than 150 years ago. But those who posit a climate crisis must admit that a small agrarian social model, where humans and nature are interdependent, is far more ecological than continuing on the infinite growth pattern of capitalism. And with the technological advancements that have occurred over the past 150 years, agrarian life is much more comfortable than in the mid 19th century. Small economic life is not for everyone but true climate defenders should be advocating for the widespread ownership of property and assist those who do want to give it a try. Instead the climate priests push owning nothing and being happy.

Its proponents have manufactured such a huge stock of political ammunition that simply denying climate change exists is a tactical mistake. A better approach is to grab this political capital and weaponize it against the climate priests. Creating ideological space for opting-out of urban degeneracy will encourage others to reject the hopelessly empty spirals of consumption, combined with soul-numbing cultural rot. A turn back towards the solidity of traditional life and its harmony with nature is the central tenet of indigenous religions from Europe and around the world. And given recent job-killing technological advances, particularly among the higher educated, learning to farm, raise animals, or produce artisanal crafts might just be better advice than learning to code was a few years ago.