Chalices of the Lie: Noble Myths and the Poison of Denial

The West still chants of victory, but the frontlines say otherwise. Ukraine's fate, like Finland’s before it, may hinge not on courage—but on timing, truth, and who dares break the Noble Lie's spell.

Despite the grim-faced EU photo ops and stern communiqués demanding Russia accept an unconditional ceasefire—and President Trump’s self-proclaimed power to enforce a 50-day halt backed only by wishful tariff threats—there is not merely no Western path to victory in Ukraine, but no end to the war in sight. Russia appears in no rush to conclude its so-called Special Military Operation; with each passing month, its position grows stronger, whether for eventual negotiations or, more ominously, for imposing terms on a broken Ukraine. The Russian’s slow, grinding advance through the Donbass continues to drain Western arsenals—limited stocks that, when push comes to shove, will always be prioritized for the golden child of U.S. military aid: Israel.

In a recent report by Seymour Hersh, a curious narrative structure emerges—one that invites analysis through the conceptual lens of Leo Strauss, the German émigré political philosopher whose work explored the role of esoteric writing, deception, and myth in political life. Strauss famously argued that regimes often require noble lies—deliberate falsehoods told by elites to preserve social cohesion or the authority of the state. These are not mere propaganda, but foundational fictions meant to reconcile order with belief.

In this light, Hersh’s reporting reads less like standard investigative journalism and more like a glimpse into a truth carefully managed for mass consumption. His central contention is that elements within the U.S. security establishment are preparing to cast aside Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, possibly in favour of General Valery Zaluzhny, the former commander-in-chief of Ukrainian forces. That premise, in itself, is unsurprising: dissatisfaction with Zelensky’s wartime leadership has surfaced before, and Zaluzhny—battle-tested, blunt, and technocratic—offers a more palatable figure to a Western alliance increasingly attuned to the limits of its investment and the perils of strategic overreach.

This portion of Hersh’s article rests on firm ground. Zelensky has spent three years performing a postmodern pastiche of Winston Churchill—rallying liberal sentiment, framing the conflict in moral absolutes, and basking in the adulation of Western parliaments. Yet the result has been a steady erosion of territory, the exposure of NATO’s industrial limits, and the creeping disillusionment of his sponsors. Now, belatedly, it appears to be dawning on Western strategists that their man in Kiev may need to channel not Churchill but Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim—the Finnish field marshal who, recognizing the futility of continued resistance, negotiated an honourable peace with Joseph Stalin after Finland’s defeat in the Winter War of 1939–40.

Three years ago, in an interview with The Economist, General Valery Zaluzhny offered a cryptic comment, heavy with implication—one that slipped past most readers, obscured by the unfamiliar historical referent and the coded gravity of the message:

“It is not yet time to appeal to Ukrainian soldiers in the way that Mannerheim appealed to Finnish soldiers. We can and should take a lot more territory.”

To decode this statement is to return to the origins of the Soviet-Finnish Winter War, where myth and military necessity collided—and where, ultimately, myth gave way.

A Winter’s War

The war began not from ideological antipathy, but from geostrategic logic. With the Nazi-Soviet Pact temporarily securing Stalin’s western frontier, attention turned to the vulnerability of Leningrad, less than thirty kilometres from the Finnish border. The Soviet leadership, anticipating future German aggression, sought territorial adjustments along the Karelian Isthmus and control of key islands in the Gulf of Finland. In exchange, Finland was offered larger tracts of Soviet land elsewhere. It was a rational, if unpalatable, demand—not imperialist rapacity, but prophylactic realpolitik.

Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, head of the Finnish Defense Forces, understood the imbalance of power. Finland’s military was ill-prepared for sustained war against the Red Army. He urged accommodation—a bitter compromise, but one grounded in sober appraisal. Helsinki’s liberal parliamentarians thought otherwise. Possessed by an inflated belief in Western support and a sentimentalized vision of national sovereignty, they rejected Stalin’s terms. War ensued. Mannerheim, though opposed to the policy, was tasked with executing it.

The conflict soon gave rise to a mythology that has endured in Western memory: of a noble David resisting a brutal Goliath. There is some truth to this. Finnish resistance was inventive and brave. Lightly armed ski troops harassed Soviet columns through the Karelian snows; the Mannerheim Line held longer than expected. But material asymmetry was implacable. The Red Army adapted. By late February, they had breached the line. The road to Helsinki stood open.

It was at this critical juncture that Mannerheim returned to his original counsel. Facing encirclement and national collapse, he urged negotiation. This time, the government listened. Stalin, aware of the strategic cost of continued occupation and perhaps chastened by earlier battlefield humiliations, imposed terms only marginally harsher than his original offer. Finland lost valuable territory and industry, but retained its independence and regime. The Soviet Union secured its buffer zone. Both sides stepped back from annihilation.

At the war’s end, Mannerheim addressed his soldiers—not in triumph, but in truth. His message was one of dignity salvaged through realism:

“Peace has been concluded between our country and the Soviet Union, an exacting peace which has ceded to Russia nearly every battlefield on which you have shed your blood… You did not want war… Yet, in spite of all bravery and spirit of sacrifice, the Government has been compelled to conclude peace… Your heroic deeds have aroused the admiration of the world.”

The deeper lesson of the Winter War is not the moral nobility of the Finnish cause, but the calculated discipline of a retreat that preserved the nation. Finland survived not because it prevailed, but because it knew when to stop—forcing its adversary to settle while retaining enough of its own sovereignty to fight another day. It was not myth but moderation that saved it.

This was the implied threat in Zaluzhny’s comments, that he would not fight to the last Ukrainian, as Western war hawks insist, but once outside support wavered, Kiev would cut its losses and make their deal with Putin.

Today, for those in the West still capable of privileging unwelcome truths over consoling illusions—those who have not imbibed the noble lie as sacrament—Finland’s outcome stands as the most realistic model left for Ukraine. Survival, not triumph; statehood preserved through strategic concession, not territorial maximalism. And only a figure like Zaluzhny, armoured in battlefield legitimacy and unburdened by the theatrical imperatives of wartime mythmaking, possesses the authority to execute such a pivot.

In this light, Seymour Hersh’s reporting—reliant though it is on the murky signals of anonymous intelligence agency briefers—emerges as a plausible glimpse into elite recalibration. One pivotal question remains: will Vladimir Putin, now in the position once held by Stalin, show the same cold restraint when dictating Ukraine’s final terms?

Ignoble Lies

Yet buried within Hersh’s seemingly straightforward account of power politics is an extraordinary claim: that Russia has suffered two million casualties since the war began—“nearly double the current public numbers,” according to Hersh’s intelligence sources. These “current public numbers” are the already highly exaggerated Ukrainian propaganda figures. The assertion that Kiev’s media manipulators are underestimating Russian war deaths by 50% is so fantastical, so extravagantly detached from battlefield realities, that it demands to be read not as a factual statement, but as a rhetorical device. And here, the legacy of Strauss becomes vital.

Strauss argued that philosophers—and, we might add, intelligence bureaucrats—writing under the shadow of totalitarian regimes, often write in two registers. One is exoteric, the public-facing narrative crafted for the common reader. The other is esoteric, buried between the lines, directed to those capable of decoding the deeper message. To protect themselves from persecution—or to advance a political objective—clever writers employ contradiction, overstatement, and allegory as camouflage.

In his Economist interview, Zaluzhny used the esoteric method by subtly bringing up Mannerheim to warn his Western sponsors that he would seek terms from Russia if they did not provide him with the military hardware required for victory.

Hersh’s anonymous source tells us that Russian casualties have reached an apocalyptic scale: two million dead, most of them highly trained soldiers, mid-level officers, and elite armour units. The implication is that Russia has exhausted itself, its army now composed of “ignorant peasants” and rusting equipment.

If this were true—if Russian forces had indeed suffered two million fatalities—then basic strategic logic would dictate a very different course of action. Far from urging Ukraine to sue for peace, NATO would be escalating support, the EU would be mobilizing in earnest, and Western special forces would be preparing their Ukrainian proxies for the next phase of advance toward the outskirts of Moscow.

And far from contemplating Zelensky’s political disposal, the West would be canonizing him as a latter-day Alexander, the supreme warlord of the democratic world—his portrait hoisted in every NATO war college, his doctrine enshrined in every future field manual.

But the opposite is happening. Western arsenals are depleted, Ukrainian forces are ceding ground, morale is visibly fraying, and calls for a ceasefire—whether immediate or deferred by fifty days—grow louder with each passing week. It is in this context that Strauss’s concept of the noble lie returns in grotesque modern form. The lie on offer is not noble in Plato’s civic-mythic sense, but strategic: a manufactured narrative, designed not to uplift but to obscure collapse and manage decline. The exoteric storyline fed to the public is one of Russian implosion; the esoteric message, for those attuned to it, is far more bleak. As the Freudian principle of projection would suggest—if not Freud himself—accusations often operate as veiled confessions. A properly Straussian reading of Hersh’s article yields a brutal subtext: the massive death toll haunting the war is not Russia’s, but Ukraine’s.

Fabricating Peace: From Tehran to Kiev

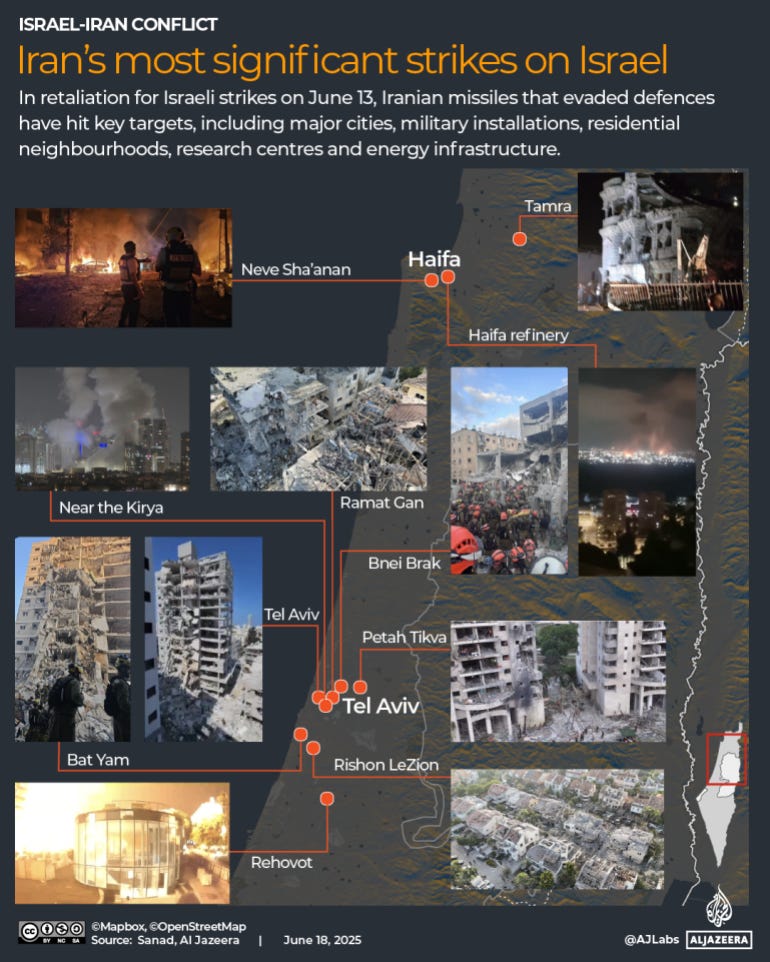

The pattern of strategic deception—the exoteric lie spoken aloud and the esoteric truth buried in silence—reappeared in even starker relief during the recent twelve-day war between Iran and Israel. That conflict, which risked engulfing the Middle East in a region-wide conflagration, ended with a whimper disguised as a trumpet blast. At its climax, President Donald Trump announced with great fanfare that U.S. B-2 bombers, deploying GBU-57 “Massive Ordnance Penetrators,” had obliterated Iran’s nuclear infrastructure in a precision night strike. It was, by his telling, a feat of techno-military grandeur, confirming American dominance and obviating further escalation.

But even the more credulous corners of the foreign policy press raised an eyebrow. Analysts across NATO capitals quietly affirmed that little, if any, meaningful damage had been done to Iran’s deeply fortified sites. Tehran, for its part, responded with only token retaliation not because it had been bludgeoned into silence, but because Washington had—through backchannels—signalled its interest in ending the war. The lie, therefore, was not so much a fabrication as a cover, designed to veil withdrawal in the language of victory.

What followed was the now-routine sanctification of untruth: those questioning the obliteration narrative were accused not of rational scepticism, but of insulting the valour and integrity of U.S. service personnel. The epistemic field was narrowed to a single acceptable noble lie—heroism plus triumph—with deviation cast as desecration.

Yet to grasp the genealogy of the concept, we must return to its origin in Plato’s Republic, where the noble lie appears not as a crude deception but as a founding political myth—a story told by rulers to ensure social harmony and civic cohesion. Plato proposed two distinct but related fictions. The first is a myth of indigeneity, a “blood and soil” narrative in which citizens are taught they were born from the same earth, siblings in the service of a common destiny.

This fiction was designed to elicit sacrifice for the polis—a metaphysical alibi for patriotism. In postmodern, progressive polities, such atavistic nationalism has long been discredited. Yet ironically, Ukraine, lionized by the very societies that claim to have moved beyond mythic ethnos, has come to depend entirely on precisely this form of collective hallucination. And, increasingly, it appears to be fraying: Telegram channels now overflow with footage of forced conscription, men violently dragged off the street in scenes that mark the passage from the noble fire of myth to the cold paralysis of truth, where ideological fervour has been replaced by a death dread that cannot be lied away.

The second part of Plato’s myth introduced a tripartite caste system, based on an alleged “metal” in each person’s soul: gold for rulers and philosophers, silver for auxiliaries and enforcers, and bronze or iron for laborers and artisans. This structure allowed for some social mobility—golden children could emerge from iron households—but more importantly, it encoded the logic of differentiated discourse. Each class was meant to receive a form of rhetoric suited to its nature. The bronze masses were to be ruled by blunt binaries: good vs. evil, hero vs. villain, our tribe vs. theirs. The silver class—today’s professional managerial class (PMC), from press secretaries to think tankers—crafted and disseminated these narratives. But for the gold, the philosopher-rulers or (in modern guise) intelligence analysts, truth was to be sacrosanct, preserved in spaces immune to political coercion, so that wise decisions might still be made based on kernels of golden truth hidden within the midst of iron and bronze myth.

In theory, then, the intelligence community and reality-based geopolitical commentators ought to function like the commissioner’s box in a sports stadium, where the tribal loyalties of the crowd and the narrative flair of the commentators give way to dispassionate assessment. The bronze fans might chant for the 49ers while the iron root for the Raiders, the silver scribes might spin their columns accordingly, but only from the commissioner’s perch can one observe the rules, penalties, revenue flows and entertainment value with clarity. Yet when even this level is infected—when the gold class begins to imbibe its own propaganda—the system corrodes. Intelligence becomes indistinguishable from ideology, and decision-making, untethered from fact, drifts toward fantasy. In the context of Ukraine, where public discourse forbids acknowledging Russian advances or Ukrainian collapse, such blindness at the summit can only hasten imperial miscalculation.

But unlike the mythic cohesion of Plato’s noble lie—designed to harmonize society under a shared fiction—Trump’s fabrication was forged in the cold furnace of strategic necessity. It was not that the truth was unknown to the gold tier of decision-makers; quite the contrary. Intelligence channels had made the situation clear: America and Israel were nearing depletion of their most advanced air defense interceptors. Iron Dome, Arrow, and THAAD systems had been stretched to the brink, and Iran, having weathered the initial bombardment, had begun to respond with far more precise, high-grade munitions.

Worse still, Israel’s shift to a counter-value strategy—targeting civilian infrastructure—threatened to provoke a broader, more dangerous Iranian response. A rapid de-escalation became imperative. Yet openly acknowledging this operational vulnerability risked not only political embarrassment, but reputational collapse. The solution was archetypal: craft a story that would end the war while preserving the illusion of triumph. A noble lie, then—not in its ideal Platonic form, but in its modern realpolitik guise—was summoned to stitch over the widening gap between strategic interest and public perception. The U.S. needed a dignified off-ramp from Iran; the truth could not provide one. The fiction of triumph, therefore, became the condition for disengagement.

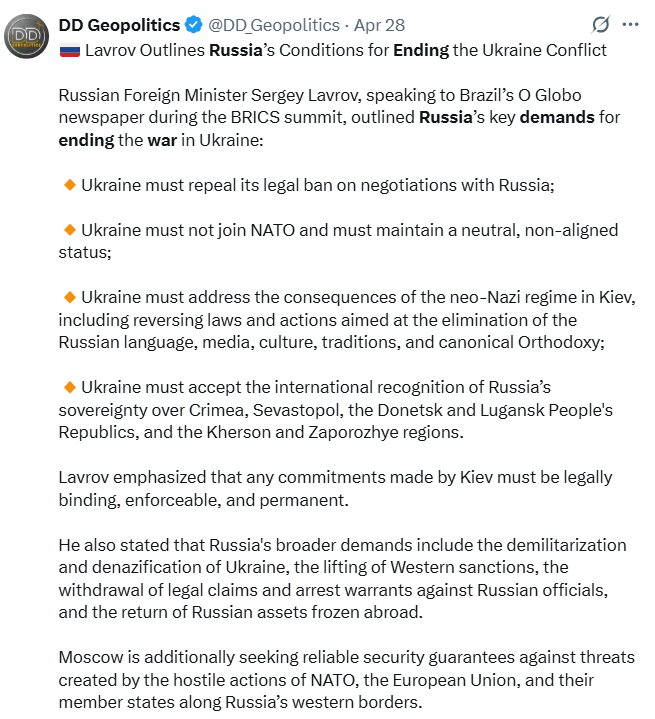

Truth or Dare in Ukraine

The war in Ukraine, still ongoing, presents a more rigid structure of demands. Unlike in the Iranian case, where temporary disengagement was acceptable to both parties, Russia insists on a settlement tantamount to recognition of victory: full Ukrainian withdrawal from the four annexed oblasts, acknowledgment of Crimea as Russian territory, an end to NATO ambitions, demilitarization, and constitutional protections for the Russian-speaking minority. In addition, Russia would expect the lifting of Western sanctions and the unfreezing of assets—effectively, the restoration of a normalized relationship on Russian terms.

This list of demands would be absurd—indeed, politically suicidal—for any Western government to entertain if Russia were truly suffering two million casualties. Were Moscow haemorrhaging men and material at that scale, the logic of attrition would compel NATO to escalate. Killing another million Russians, or pushing the front into Moscow’s leafy suburbs, would be strategically irresistible. That none of this is happening, and that calls for ceasefire now multiply across NATO capitals, indicates which story is exoteric performance and which is esoteric warning.

To this, one might append a literary footnote. In Ibsen’s The Wild Duck, the young truth-teller Gregers Werle insists on revealing a long-suppressed family secret, convinced that freedom lies in absolute honesty. But when the veils are stripped away, the result is destruction, not emancipation. “If you take the life-lie from a man,” one character observes, “you take away his happiness.” And so, many political truths, especially in declining hegemonies, are transformed into “regime-lies”—necessary to maintain the illusion of coherence, capability, and control.

Today, the West finds itself in such a posture: unable to admit the limits of its own power, unwilling to pay the price of true negotiation, and so trapped within the exoteric myths it tells to its own publics. Whether in Kiev or Tehran, the lie is rarely noble, but always necessary. And perhaps—as with the Soviet Union in its final years—the system will continue to speak of triumph even as it negotiates defeat.

Hello, interesting ideas, and smart to bring up the idea of esoteric hidden writing by Leo Strauss. The only problem is that I don't see much sign of that now. I mostly see Trump and his administration bumbling along, and making one blunder after another not only in terms of communication, but also in terms of action.

Suffice to mention his 180 comments about Epstein, about his MAGA base, on the tariffs, his studid attack on Iran, his failure with Gaza genocide, his hesitation on Russia... I wrote about this bumbling some time ago, and it seems in my opinion to be completely correct today:

https://finnandreen.substack.com/p/a-bumbling-trump-administration-has?r=ewq2s

Interesting analysis. In regard to Zaluzhny and the Finnish option, many commentators have alluded to the influence of the neo-nazi Azov element and the fact that he has quite strong links to this group. The same sources say that Azov would likely kill any leader who concluded a peace with Russia.

Do you have a view on this? Has the successful war of attrition weakened Azov influence and attitudes and have they become more “realistic” and perhaps reached the point of “better to live to fight another day”?