Badman Theory

A Tale of Three Quagmires: Korea, Vietnam, Ukraine—and Three Theories to End War. From Eisenhower’s Good Cop/Bad Cop to Nixon’s Madman to Trump’s Badman Theory.

If celebrity deaths come in threes, so do unwinnable wars—started or escalated by Democrats and dumped into the laps of Republican presidents. Korea, Vietnam, and Ukraine, each ignited under Democratic administrations. As these conflicts deepened into quagmires, the Democratic architects—Truman, LBJ, and Biden—found themselves forced to abandon their re-election campaigns.

In all three cases, the Democratic Party elite, rather than the electorate, pushed through unpopular second choices: Adlai Stevenson in 1952, Hubert Humphrey in 1968, and Kamala Harris in 2024. Each went on to lose to Republican challengers—Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, and Donald Trump 2.0, respectively. All three quagmires then became the burdens of Republican successors.

These Republican victors, in turn, formed duets with their Secretaries of State, crafting distinct strategies to extricate the U.S. from its inherited messes. Eisenhower and John Foster Dulles perfected a good cop/bad cop routine, rattling nuclear cages to force communists in Korea and China to the negotiating table. Nixon, with his infamous “Madman Theory,” paired wild brinkmanship with Henry Kissinger’s cerebral “Wiseman Theory,” leveraging chaos and calculation to pressure Moscow and Hanoi into talks.

Now, a little more than a month into his second term, Donald Trump, inspired by his predecessors but with his own uniquely brash twist, is unleashing his “Badman Theory,” with Marco Rubio playing the role of his more agreeable “Boy Wonder” sidekick. Gone are the days of the U.S. as a “Redeemer Nation,” championing the free world with moral fervour. All the old norms are shattering, it’s time for the free world to start paying their way.

Under the Orange Badman, it’s all about the Benjamins—the high-minded ideals of liberal interventionism replaced by a businessman’s drive to fill America’s empty coffers with filthy lucre extracted from abroad. Ending wars saves lives and fosters prosperity, so the term Badman also celebrates breaking bad norms—upending the status quo to forge a new, pragmatic foreign policy path forward.

But here’s the twist: Trump’s “Badman Theory” isn’t aimed at Moscow or Beijing. No, in true Badman fashion, his strategy targets the so-called good guys. It’s designed to force Brussels and Kiev onto the horns of a dilemma: make serious concessions in Ukraine or kiss the U.S. goodbye as a security partner in NATO. The Badman’s game isn’t about saving the world or even policing it—it’s about reshaping the world to America’s advantage. In this geopolitical framework, the strong thrive, and nice guys finish last.

Three great powers—China, Russia (and its Soviet predecessor), and the United States—have clashed directly and through proxies in Korea, Vietnam, and now Ukraine. Over the decades, they have fought each other, danced together, split apart, and come back together. If Trump’s Badman Theory bears fruit, we may return to the world of Thucydides’ Ancient Greece, where these three great powers do as they will, and the weak suffer as they must. But then again, hasn’t it always been that way? After all, that Nord Stream pipeline didn’t blow itself up, did it?

The word “bad” is a linguistic shapeshifter, capable of conveying condemnation or coolness depending on context. The meme “Orange Man Bad” exemplifies this duality: initially a critique of Donald Trump’s presidency, it was later reclaimed by his supporters as a sarcastic jab at his detractors. Similarly, the TV series “Breaking Bad” redefines “bad” as a moral descent, capturing the allure of rebellion and the complexity of human choices. In Trump’s “Badman Theory,” the term takes on yet another meaning—a willingness to disrupt norms, wield power unapologetically, all while never having to say, “my bad.”

War in Korea

Mao’s 1949 victory in the Chinese Civil War reshaped global power, bringing the world’s most populous nation under communist rule and cementing the 1950 Sino-Soviet Alliance. For Stalin, Mao’s rise was both an asset and a threat—expanding communism while introducing a rival. Viewing Korea as a low-risk battleground, Stalin cautiously endorsed Kim Il-sung’s push for reunification of the Korean peninsula by force.

The Korean War erupted in 1950 with rapid advances and retreats. North Korean forces nearly overran the South before a U.S.-led counteroffensive pushed them to China’s border. This provoked Mao, whose troops surged across the Yalu, forcing a chaotic retreat. By 1951, the war settled into a brutal stalemate near the 38th parallel.

Enter Eisenhower

Eisenhower’s arrival in 1953 transformed the war’s playbook, replacing attritional battle with a new strategy of power and threat. With John Foster Dulles as his hard-line envoy, Eisenhower played the calm statesman in public while delivering nuclear ultimatums through intermediaries like India’s Nehru in private.

Dulles, the bad cop, threatened “massive retaliation,” while Eisenhower, the good cop in public, wielded the silent menace of atomic fire behind the curtain. This performance—bluster and veiled threats mixed with an image of sober leadership for domestic consumption—aimed to fracture communist resolve while masking America’s own strategic hesitations.

But the communists were already seeking a pause. China, having rescued North Korea from collapse, now faced a costly, grinding war. Meanwhile, relentless U.S. bombing and Eisenhower’s nuclear hints signalled that escalation could be catastrophic. For Mao and Kim Il-sung, negotiations offered a way to consolidate gains while avoiding further devastation.

The July 27, 1953, armistice was no victory, just an uneasy pause. The DMZ, a barren no-man’s-land, became a monument to deadlock, dividing not just two Koreas but two worlds. Eisenhower’s nuclear whispers may have nudged the communists to the table, but the peace they brokered was a ceasefire without resolution.

However, from this truce emerged enduring U.S. guarantees to South Korea, reinforced by a massive tripwire force at the DMZ and troops stationed on U.S. soil, primed for Korean deployment. These were not mere pledges but a fortress of commitment—an ironclad testament to Cold War containment, etched in blood and steel.

Recently, Western leaders wishcasted the end of Ukraine’s war onto Korea’s frozen conflict, imagining a ceasefire patrolled by entrenched armies. But as Russia advanced through Donbas in 2024, this hope unravelled. Only the most optimistic still clung to the illusion, though publicly, the narrative endured—a comforting veil over a war that refused to be tamed.

Today, Ukraine demands powerful security guarantees modelled on those still holding a fragile peace in Korea. Yet, unlike Korea, where the U.S. commitment was ironclad, Ukraine faces a world where such promises are no longer guaranteed. The ghosts of past guarantees loom large, a reminder of what could have been—and what may never be.

Madmen of Harvard

Nixon’s Madman Theory is often dismissed today as an ignorant relic of Cold War brinkmanship. Yet, between Korea and Vietnam, it was not only taken seriously but actively developed at Harvard. One of its key architects was Daniel Ellsberg, then a RAND Corporation strategist, who later gained fame as an anti-war activist after leaking the Pentagon Papers. During this period, Ellsberg’s work helped shape the very strategy Nixon would later adopt, turning calculated unpredictability into a tool of global diplomacy.

As detailed in Nixon’s Nuclear Specter by William Burr and Jeffrey P. Kimball, Ellsberg’s exploration of coercion and unpredictability was deeply influenced by Adolf Hitler’s strategies. Ellsberg delivered two lectures on the uses of blackmail and madness before Henry Kissinger’s Harvard seminar on defense and international issues. These lectures were followed by a series of public talks and radio broadcasts in Boston, collectively titled “The Art of Coercion.” Among the specific topics Ellsberg addressed were “The Theory and Practice of Blackmail,” “Presidents as Perfect Detonators,” “The Threat of Violence,” “The Incentives to Preemptive Attack,” and “The Political Uses of Madness.”

Ellsberg’s analysis drew heavily on Hitler’s policy of unpredictability, which he argued could be adapted to modern statecraft. The idea was simple yet radical: by projecting an image of irrationality and unpredictability, a leader could coerce adversaries into concessions, deter aggression, and manipulate the geopolitical chessboard. This concept resonated deeply with Nixon, who saw in it a way to break the stalemates of Cold War diplomacy.

Eisenhower and Dulles interpreted the Korean War’s conclusion as a triumph of nuclear diplomacy, a narrative that became Republican Party lore and later conventional wisdom in the U.S.

Nixon, as Eisenhower’s vice president, closely observed their strategies, attending National Security Council meetings and forging a strong bond with Dulles—a relationship that contrasted sharply with Eisenhower’s aloof, at times dismissive, attitude toward him. This Korean experience deeply influenced Nixon’s own approach to foreign policy, as noted by Burr and Kimball.

Enter Nixon

When Nixon and Kissinger entered office in 1969, they inherited a quagmire in Vietnam, a war that had already cost tens of thousands of American lives and deeply divided the nation. Their strategy was twofold: escalate militarily to force North Vietnam to the negotiating table while simultaneously pursuing a policy of "Vietnamization," which aimed to gradually transfer combat responsibilities to South Vietnamese forces.

This dual approach culminated in the secret bombings of Cambodia and Laos—to intimidate North Vietnam into concessions. At the same time, Kissinger, the consummate diplomat and intellectual, employed a “Wiseman Theory,” engaging in secret backchannel negotiations with North Vietnam’s Le Duc Tho.

Together, Nixon’s brinksmanship and Kissinger’s diplomacy formed a paradoxical partnership: one destabilizing through chaos, the other restabilizing through reason—a delicate dance of force and finesse that sought to extract America from a war it could not win.

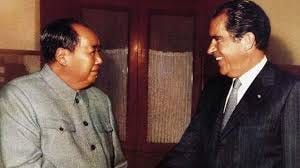

Driving the Wedge: Nixon Goes to China

Nixon’s diplomatic opening to China in the early 1970s added a new dimension to this strategy. By signalling a willingness to downgrade U.S. ties with Taiwan—most notably through the 1972 Shanghai Communiqué, which acknowledged the One China principle—Nixon created the political space needed to court Peking.

This move was not merely a gesture of goodwill; it was a calculated effort to exploit the deepening rift between China and the Soviet Union. By aligning with Mao’s China, Nixon effectively turned the Sino-Soviet split into a geopolitical lever, isolating Moscow and forcing it to contend with a two-front Cold War.

Facing the prospect of strategic encirclement and a potential two-front conflict, Moscow had little choice but to engage more constructively with Washington, including on the issue of Vietnam. In turn, the Soviets, now wary of losing their foothold in Southeast Asia, began to exert pressure on Hanoi to negotiate, urging the North Vietnamese to consider a settlement that would prevent a total U.S.-China rapprochement at their expense.

Thus, the Sino-Soviet split became a hidden fulcrum in the Vietnam peace process, as Nixon and Kissinger skilfully turned communist disunity into a tool of American diplomacy. Today, a potential U.S.-EU split may serve as the catalyst for peace in Ukraine, echoing the same strategy of leveraging division to achieve resolution.

Linebacker Blitz

Kissinger’s negotiations with Le Duc Tho seesawed between progress and stalemate as both sides sought leverage. The 1968 Tet Offensive, though a psychological blow to the U.S., was a military disaster for the Viet Cong, crippling their capacity. Meanwhile, Nixon’s relentless bombing—particularly Operations Linebacker and Linebacker II—devastated North Vietnam’s infrastructure and supply lines, forcing Hanoi to reconsider its strategy.

A breakthrough came in late 1972 when, battered by bombing and Nixon’s re-election, North Vietnam accepted terms allowing U.S. withdrawal while leaving South Vietnam’s fate unresolved. The Paris Peace Accords, signed on January 27, 1973, promised a ceasefire, U.S. withdrawal, and POW returns—but lacked enforcement, leaving South Vietnam vulnerable.

Unlike South Korea, South Vietnam received no enduring U.S. military presence, only fragile political assurances. By 1975, as Congress and public support evaporated, North Vietnam’s final offensive crushed Saigon, unifying the country under communist rule. The collapse fuelled a "stab-in-the-back" myth that haunted U.S. foreign policy, turning Nixon’s “peace with honor” into a farce.

Breaking Mad

Thomas Schelling’s Arms and Influence offers a striking metaphor for the dynamics of coercion and deterrence in international relations through the tale of the “stunted little chemist” from Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent. This anarchist, armed with nitro-glycerine and an unshakable resolve to use it, embodies the two essential qualities needed to move adversaries: powerful military capacity and the character to wield it.

The chemist’s “stuff”—his destructive potential—is meaningless without the perception that he is willing to detonate it, even at the cost of his own life. His safety, he explains, lies not in the explosive itself but in the absolute belief of others in his willingness to use it. This duality—capacity and character—forms the bedrock of what Schelling calls the “art of commitment,” and it is central to understanding the success of strategies like Nixon’s “Madman Theory” or Trump’s “Badman Theory.”

The first element, powerful military capacity, is the tangible foundation of any coercive strategy. For the chemist, it is the nitro-glycerine; for a state, it is the arsenal of weapons, economic leverage, or geopolitical influence that can inflict unacceptable costs on an adversary.

Yet, capacity alone is insufficient. The second element, character, is what transforms potential into credible threat. The chemist’s safety depends on the belief that he is deadly—perhaps impulsive, irrational, or even suicidal. This perception of unpredictability is what makes him dangerous.

The final ingredient is automaticity—the sense that escalation or retaliation is inevitable, not a matter of choice but of necessity. The chemist’s hollow ball, primed to detonate at the slightest pressure, symbolizes this principle. For states, automaticity can be achieved through mechanisms like tripwire forces, mutual defense treaties, or public declarations of red lines.

I Am Ironman

Russian President Putin’s strategy against the West follows an “Ironman Theory”—an unyielding, calculated approach that fuses resolve with firepower. Like Conrad’s “stunted little chemist” in The Secret Agent, Putin wields his own versions of nitro-glycerine: the Oreshnik missile system, the constitutional annexation of four Ukrainian oblasts plus Crimea, and a steadfast refusal to allow Ukraine into NATO. These aren’t bluffs but tools of coercion, reinforced by his ability to endure sanctions, sustain battlefield gains, and maintain control despite international strain. His strength lies in the belief that he will never back down—a leader defined not by madness or bravado but by sheer inevitability.

Although Putin occasionally engages in nuclear sabre-rattling, as Nixon discovered, a Madman Theory soon runs into the MAD impasse. The spectre of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) dampens any nuclear brinkmanship. Are statemen really going to risk thermonuclear destruction of the earth over a messy regional war?

Russia’s Oreshnik missile system, however, is a devastating conventional weapon, capable of saturation strikes that fly well under the nuclear taboo. It is the nitro-glycerine Putin can credibly threaten to use, a tool of coercion without crossing the ultimate red line.

From his Badman Theory perspective, Trump understands the futility of attacking the powerful and recognizes that it is better to align with Putin than to oppose him. The Badman’s game is not about confronting strength but exploiting weakness.

Enter Sandman

Zelensky’s Sandman Theory—a blend of Messianic resolve and zealous overreach—is aimed primarily at maintaining his grip on power in Ukraine. Like a tragic lullaby, his vision has driven the nation into gruelling battles, often with inadequate firepower, resulting in nightmarish levels of dead and wounded. Unlike Putin’s Ironman or Nixon’s Madman, Zelensky lacks the domestic military “nitro-glycerine” to match his will, relying instead on limited Western aid that slows but cannot halt Russia’s advances.

This imbalance has led to costly miscalculations, from the failed 2023 Zaporizhzhia counteroffensive to the disastrous Kursk “kill bag” operation, which has left the steppes littered with the fallen. While Zelensky’s belief in Ukraine’s survival appears unshakable, critics argue that the war persists due to his unquenchable desire for power.

On the other hand, Zelensky faces an ultranationalist problem. In many ways, he is a hostage to factions like the Azov Brigade. A theatre kid who has lost himself in the role of a Messianic statesman, Zelensky knows that one false move toward peace could shatter his toxic symbiosis with Azov. His collapse would be as sudden as a junkyard heavy electric magnet machine releasing its load into a scrap heap. In the end, Zelensky risks becoming a comic book Churchill—crucified on an Iron Cross.

In the Oval Office on Friday, February 28th, Trump and JD Vance delivered a humiliating scolding to Zelensky. Trump knows exactly who the radicals are—lurking behind the Ukrainian curtain, pulling the levers of power. If he can push Zelensky off center stage, the ultranationalists will be forced to rush to the fore. What delicious irony it will be for the man often labeled “Literally Hitler” to watch the good Europeans squirm as they are compelled, for the sake of Project Ukraine, to defend tattooed ethno-nationalists far more radical than any so-called “far right” figures back home.

Strawman Union

Europe’s approach to Ukraine follows a Strawman Theory—a façade of strength that collapses under the slightest scrutiny. Militarily weak and politically divided, Europe postures bravely toward Russia but constantly glances over its shoulder to ensure Uncle Sam is close by.

Europe’s strategy resembles “Let’s you and him fight”—seeking U.S. protection while avoiding direct confrontation. Macron and Starmer plan to deploy “peacekeepers” in a ceasefire scenario, not to ensure stability but to bait Russia into attacking British and French forces. Emotional blackmail will follow as the Strawman tries to trick the U.S. into intervention.

This gambit was laid bare in a press conference when Trump was asked if the U.S. would aid British troops attacked by Russia. Dodging the trap, he quipped, “They don’t need much help, they can take care of themselves,” before pointedly asking, “Could you take on Russia alone?” Starmer’s stunned silence revealed the truth: Europe cannot.

Europe’s rhetoric, like its strategy, is a house of straw—grandiose but fragile. And the Big Badman will huff, and he’ll puff, and he’ll blow their house in.

Fourth and Long in Ukraine

In American football, “fourth and long” signals a choice—risk it all or punt and play defense. Many in MAGA, including Steve Bannon, urge Trump to “walk the f*ck away” from Ukraine. Instead of imitating Nixon’s tough guy linebacker image, Bannon wants Trump to wash his hands of Ukraine by launching Operation Punter—kicking the conflict deep into Europe’s territory, where Macron and Starmer seem eager to trap themselves into a coffin corner.

Trump does seem, at times, to be lining up in punt formation on Ukraine. But will it be a trick play? Trump is deploying his Badman Theory—not against Russia, but against the Collective West. He knows he can’t break Putin’s Ironman resolve, nor can he split the growing Sino-Russian alliance. If you can’t beat them, join them—which means Trump may move closer to Russia and China. But in the meantime, his only play to end hostilities in Ukraine is to force Brussels and Kiev to finally accept defeat.

Whereas Nixon drove a wedge between China and the USSR, Trump is threatening to cleave the West itself, signalling he might abandon NATO and wants Europe to take over the job of propping up Ukraine, knowing full well they will fail. Bluff or not, he’s already dismantling key tools of U.S. imperialism: USAID and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) have suspended operations, and he’s slapped 25% tariffs on the EU.

Adding to the drama, Vice President JD Vance recently scolded European leaders, likening the EU to a “latter-day Communist bloc.” Meanwhile, in a move eerily reminiscent of Soviet-era repression, Romanian officials arrested leading presidential candidate and EU sceptic Călin Georgescu, further deepening the transatlantic divide.

Ghosts of Security Guarantees Past

At the heart of any resolution to the Ukraine War lies an impossible demand: ironclad U.S. security guarantees. Ukraine dreams of a Korean-style fortress of American commitments, yet Trump refuses to offer even the hollow assurances once given to South Vietnam. His stance is clear: no NATO, no guarantees—knowing Ukraine would exploit them to provoke Russia into a direct confrontation with the US. It is the same stance proffered by Biden.

Sensing Trump’s victory back in September 2024, Zelensky offered a “victory plan”—a dowry of rare earth riches in exchange for long-term U.S. protection. The deal was packaged not for the moral preening of the Biden Administration, but for the transactional proclivities of a Badman. The current pact being negotiated between Trump and Zelensky is an empty shell, a mumble where a roar was sought. The deal is full of holes and much more aspirational than legal. It grants the US 50% of Ukrainian resources profits into perpetuity, in return for the vaguest mentions of security. Trump has announced that the fact the US is on the ground in Ukraine will stop any attacks. A far cry from Korea, or even Vietnam but anything more would put the US and Russia on a collision course.

What was all too real, however, was the brutal dressing down Trump and VP JD Vance delivered to Zelensky in the Oval Office, broadcast to the world. The Sandman did not at all seem to share their concerns about ending the sacrificial slaughter of Slavic men on the steppes.

Threepeat

It’s not just celebrity deaths that come in threes. In Korea, Vietnam, and Ukraine, history is “threepeating” itself. Korea ended in a tragic but stable stalemate, a frozen conflict where the lines of division hardened into permanence. Vietnam concluded as a farce, a spectacle of superpower impotence that, paradoxically, resulted in a unified and prospering Vietnam today. The lesson is clear: a decisive victory by any side is better than a perpetual stalemate. But is a decisive compromise possible in Ukraine? Or is it heading towards the nihilism of perpetual war?

Following Zelensky’s curb-stomping during an Oval Office news conference, his days in power may be numbered. Sacrificed as a scapegoat, his removal could open the door for Russians and Ukrainians to begin the slow, painful work of healing—a bitter pill to swallow, but one that might finally stanch the bleeding. In the end, Trump’s Badman Theory have served as the disruptive catalyst, using chaos to shatter automatic modes of thought and create the mental opening needed to write new scripts for peace.

Interesting historical perspective on current events once again. The madman tag on Trump , Iron man tag on Putin seem pretty accurate.

Not sure about the Sandman tag on the other pathetic puff ball , not sure he merits one. Trump can certainly do a Nixon, not sure he has a Kissinger (but Vance looks promising).

To the guy who complains the article is too long , I don’t think so , this is what historical based analysis of current affairs takes.

Not like the mass produced, pre-packaged microwave reheats the MSM production line churns out.

From “Security Queens” to “Madman, Badman, Ironman, Sandman”. Great perspective again.